By 苏剑林 | December 15, 2024

In this article, we once again focus on the acceleration of sampling in diffusion models. As is well known, there are two main approaches to sampling acceleration: developing more efficient solvers or post-distillation. However, as observed by the author, apart from SiD introduced in previous articles, both of these schemes rarely achieve results that reduce the generation process to a single step. Although SiD can achieve single-step generation, it requires additional distillation costs and involves a GAN-like alternating training process, which feels somewhat unsatisfying.

The work to be introduced in this article is "One Step Diffusion via Shortcut Models". Its breakthrough idea is to treat the generation step size as a conditional input to the diffusion model and add an intuitive regularization term to the training objective. This allows for the direct and stable training of models capable of single-step generation, making it a classic piece of simple yet effective work.

ODE Diffusion

The conclusions of the original paper are based on ODE-based diffusion models. The theoretical foundations of ODE-based diffusion have been introduced multiple times in this series (in parts VI, XII, XIV, XV, and XVII). The simplest way to understand it is from the perspective of ReFlow in XVII, which we briefly repeat here.

Assume $\boldsymbol{x}_0 \sim p_0(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$ is a random noise sampled from a prior distribution, and $\boldsymbol{x}_1 \sim p_1(\boldsymbol{x}_1)$ is a real sample from the target distribution (Note: in previous articles, $\boldsymbol{x}_T$ was noise and $\boldsymbol{x}_0$ was the target sample; here, for convenience, it's reversed). ReFlow allows us to specify any trajectory from $\boldsymbol{x}_0$ to $\boldsymbol{x}_1$. The simplest trajectory is naturally a straight line:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{x}_t = (1-t)\boldsymbol{x}_0 + t \boldsymbol{x}_1\label{eq:line}\end{equation}

Taking the derivative on both sides, we get the ODE it satisfies:

\begin{equation}\frac{d\boldsymbol{x}_t}{dt} = \boldsymbol{x}_1 - \boldsymbol{x}_0\end{equation}

While this ODE is simple, it is practically useless because we want to generate $\boldsymbol{x}_1$ from $\boldsymbol{x}_0$ through the ODE, yet the equation above explicitly depends on $\boldsymbol{x}_1$. To solve this, a simple idea is to "learn a function of $\boldsymbol{x}_t$ to approximate $\boldsymbol{x}_1 - \boldsymbol{x}_0$." After learning it, we use it to replace $\boldsymbol{x}_1 - \boldsymbol{x}_0$:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{\theta}^* = \mathop{\text{argmin}}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p_0(\boldsymbol{x}_0),\boldsymbol{x}_1\sim p_1(\boldsymbol{x}_1)}\left[\|\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t) - (\boldsymbol{x}_1 - \boldsymbol{x}_0)\|^2\right]\label{eq:loss}\end{equation}

and

\begin{equation}\frac{d\boldsymbol{x}_t}{dt} = \boldsymbol{x}_1 - \boldsymbol{x}_0\quad\Rightarrow\quad\frac{d\boldsymbol{x}_t}{dt} = \boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}^*}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)\label{eq:ode-core}\end{equation}

This is ReFlow. There is still a theoretical proof missing here—that an ODE obtained by fitting $\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)$ via squared error can indeed generate the desired distribution. For this part, readers can refer to "Generative Diffusion Models (17): General Steps to Construct ODEs (Part 2)".

Step Size Self-Consistency

Assuming we already have $\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)$, we can achieve the transformation from $\boldsymbol{x}_0$ to $\boldsymbol{x}_1$ by solving the differential equation $\frac{d\boldsymbol{x}_t}{dt} = \boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)$. The key point is "differential equation," but in reality, we cannot compute the differential equation exactly; we can only compute its "difference equation":

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{x}_{t + \epsilon} - \boldsymbol{x}_t = \boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t) \epsilon\label{eq:de}\end{equation}

This difference equation is the "Euler approximation" of the original ODE. The degree of approximation depends on the step size $\epsilon$. As $\epsilon \to 0$, it exactly equals the original ODE; in other words, smaller step sizes are more accurate. However, the number of generation steps is $1/\epsilon$, and we want as few steps as possible. This means we cannot use step sizes that are too small—ideally $\epsilon = 1$, so that $\boldsymbol{x}_1 = \boldsymbol{x}_0 + \boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_0, 0)$, completing the generation in a single step.

The problem is that if we directly substitute a large step size into the equation above, the resulting $\boldsymbol{x}_1$ will inevitably deviate significantly from the exact solution. This is where the ingenious concept of the original paper (hereafter "Shortcut Models") comes in: it proposes that the model $\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)$ shouldn't just be a function of $\boldsymbol{x}_t$ and $t$, but also a function of the step size $\epsilon$. This way, the difference equation \eqref{eq:de} can adapt to the step size:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{x}_{t + \epsilon} - \boldsymbol{x}_t = \boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t, \epsilon) \epsilon\end{equation}

The objective \eqref{eq:loss} trains the exact ODE model, so it trains the model for $\epsilon = 0$:

\begin{equation}\mathcal{L}_1 = \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p_0(\boldsymbol{x}_0),\boldsymbol{x}_1\sim p_1(\boldsymbol{x}_1)}\left[\frac{1}{2}\|\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t, 0) - (\boldsymbol{x}_1 - \boldsymbol{x}_0)\|^2\right]\end{equation}

How then do we train the part where $\epsilon > 0$? Our goal is to minimize the number of steps, which is equivalent to wanting "one step with double the step size to equal two steps with single step size":

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{x}_t + \boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t, 2\epsilon) 2\epsilon = \color{green}{\underbrace{\boldsymbol{x}_t + \boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t, \epsilon) \epsilon}_{\tilde{\boldsymbol{x}}_{t+\epsilon}}} + \boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\big(\color{green}{\underbrace{\boldsymbol{x}_t + \boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t, \epsilon) \epsilon}_{\tilde{\boldsymbol{x}}_{t+\epsilon}}}, t+\epsilon, \epsilon\big) \epsilon\label{eq:cond}\end{equation}

That is, $\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t, 2\epsilon) = [\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t, \epsilon) + \boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\color{green}{\tilde{\boldsymbol{x}}_{t+\epsilon}}, t+\epsilon, \epsilon)] / 2$. To achieve this, we add a self-consistency loss function:

\begin{equation}\mathcal{L}_2 = \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p_0(\boldsymbol{x}_0),\boldsymbol{x}_1\sim p_1(\boldsymbol{x}_1)}\left[\|\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t, 2\epsilon) - [\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t, \epsilon)+ \boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\color{green}{\tilde{\boldsymbol{x}}_{t+\epsilon}}, t+\epsilon, \epsilon) ]/2\|^2\right]\end{equation}

The sum of $\mathcal{L}_1$ and $\mathcal{L}_2$ constitutes the loss function for the Shortcut model.

(Note: A reader pointed out that a prior work, "Consistency Trajectory Models: Learning Probability Flow ODE Trajectory of Diffusion", proposed taking the starting and ending points of discretized time as conditional inputs. Once the start and end points are specified, the step size is effectively determined, so the Shortcut approach of using step size as input is not entirely novel.)

Model Details

The above constitutes almost all the theoretical content of the Shortcut model. It is precise and concise, but moving from theory to experiment requires some details, such as how to integrate the step size $\epsilon$ into the model.

First, when training $\mathcal{L}_2$, the Shortcut model does not sample $\epsilon$ uniformly from $[0, 1]$. Instead, it sets a minimum step size of $2^{-7}$ and then doubles it up to 1, meaning all non-zero step sizes take only 8 values: $\{2^{-7}, 2^{-6}, 2^{-5}, 2^{-4}, 2^{-3}, 2^{-2}, 2^{-1}, 1\}$. $\mathcal{L}_2$ is trained by uniformly sampling from the first 7 values. As a result, the values of $\epsilon$ are finite (9 including 0), so the Shortcut model inputs $\epsilon$ directly as an embedding, which is added to the embedding of $t$.

Second, note that the computational cost of $\mathcal{L}_2$ is higher than $\mathcal{L}_1$ because the term $\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\tilde{\boldsymbol{x}}_{t+\epsilon}, t, \epsilon)$ requires two forward passes. Thus, the implementation in the paper uses 3/4 of the samples in each batch for $\mathcal{L}_1$ and 1/4 for $\mathcal{L}_2$. This operation not only saves computation but also adjusts the weights of $\mathcal{L}_1$ and $\mathcal{L}_2$. Since $\mathcal{L}_2$ is easier to train than $\mathcal{L}_1$, its training sample size can be appropriately smaller.

Furthermore, in practice, the paper fine-tunes $\mathcal{L}_2$ by adding a stop gradient operator:

\begin{equation}\mathcal{L}_2 = \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p_0(\boldsymbol{x}_0),\boldsymbol{x}_1\sim p_1(\boldsymbol{x}_1)}\left[\|\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t, 2\epsilon) - \color{skyblue}{\text{sg}[}\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t, \epsilon)+ \boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\color{green}{\tilde{\boldsymbol{x}}_{t+\epsilon}}, t+\epsilon, \epsilon) \color{skyblue}{]}/2\|^2\right]\end{equation}

Why do this? According to the author's reply, this is a common practice in self-supervised learning; the part wrapped in stop gradient acts as the target and should not have gradients, similar to unsupervised learning schemes like BYOL and SimSiam. However, in my view, the greatest value of this operation is saving training costs, as the term $\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\tilde{\boldsymbol{x}}_{t+\epsilon}, t, \epsilon)$ involves two forward passes; backpropagating through it would double the computation.

Experimental Results

Now let's look at the experimental results of the Shortcut model. It appears to be the best single-stage trained diffusion model for single-step generation currently available:

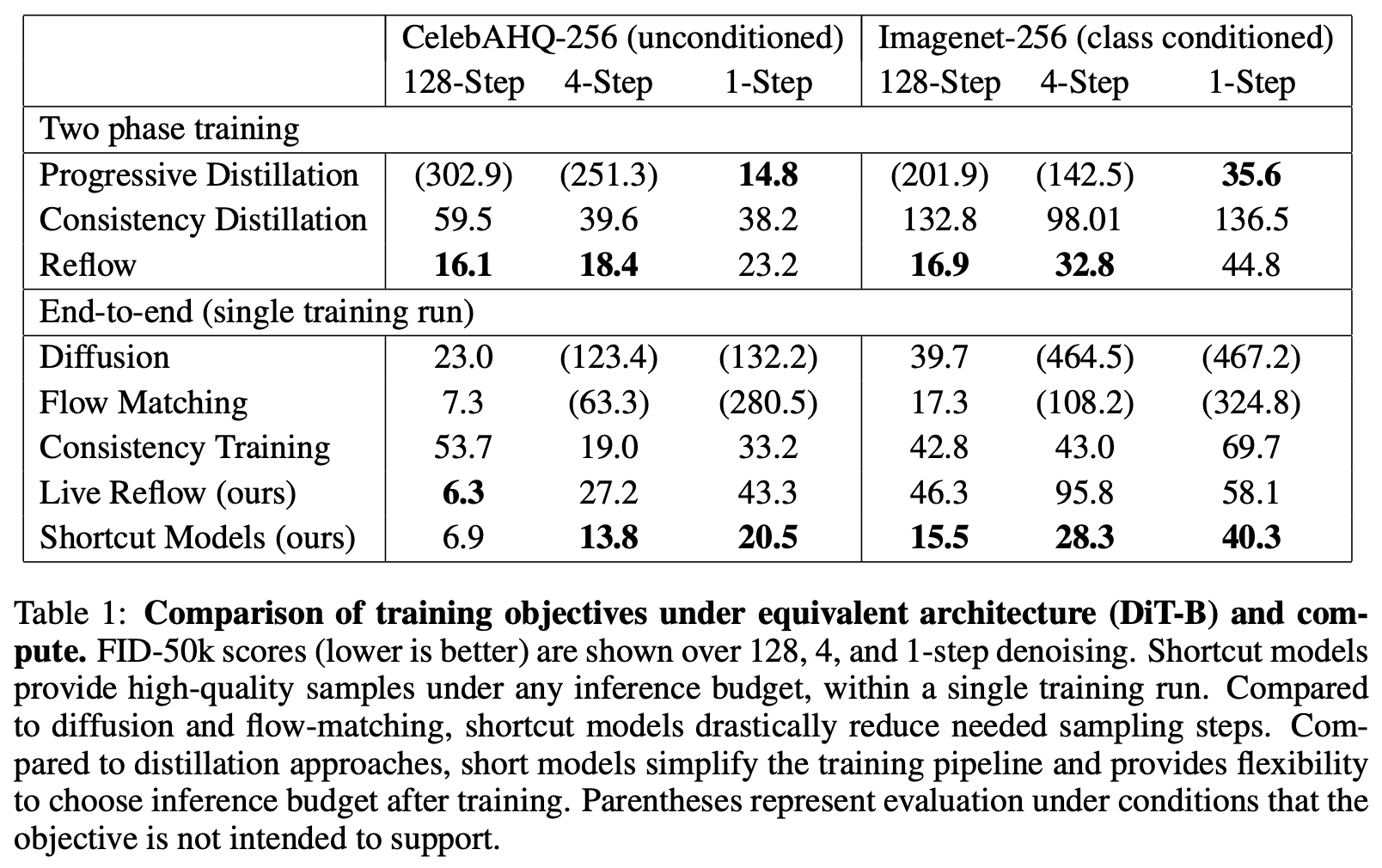

Evaluation of generation quality of various diffusion models

Here are actual sampling results:

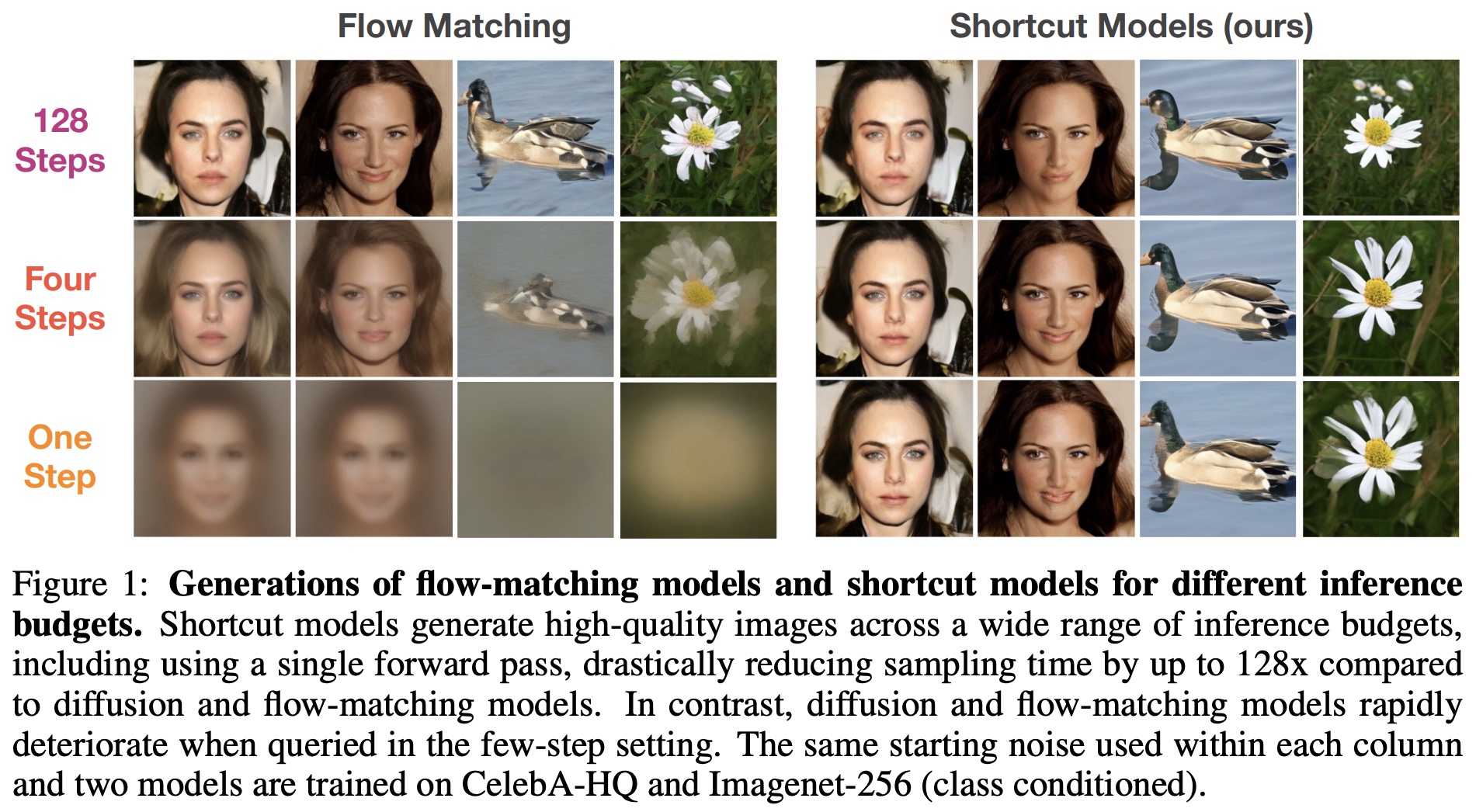

Comparison of actual sampling results between Flow Matching and Shortcut Model

However, upon close inspection of the samples from single-step generation, some visible artifacts remain. So, while the Shortcut model has made significant progress compared to previous single-stage training schemes, there is still obvious room for improvement.

The author has open-sourced the code for the Shortcut model; the GitHub link is:

https://github.com/kvfrans/shortcut-models

By the way, the Shortcut model was submitted to ICLR 2025 and received unanimous praise from reviewers (all scores of 8).

Further Reflections

Seeing the Shortcut model, what related works come to mind? One that I thought of, which might be unexpected, is AMED, which we introduced in "Generative Diffusion Models (21): Accelerating ODE Sampling with Mean Value Theorem".

The underlying philosophy of Shortcut Models and AMED is similar. Both have realized that relying solely on complex higher-order solvers to reduce the NFE (Number of Function Evaluations) to single digits is already very difficult, let alone achieving single-step generation. Consequently, they both agree that what truly needs changing is not the solver, but the model. How should it change? AMED utilized the "Mean Value Theorem for Integrals": by integrating both sides of the ODE, we have the exact identity

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{x}_{t + \epsilon} - \boldsymbol{x}_t = \int_t^{t + \epsilon}\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_{\tau}, \tau) d\tau\end{equation}

Analogous to the Mean Value Theorem for definite integrals, we can find an $s \in [t, t + \epsilon]$ such that

\begin{equation}\frac{1}{\epsilon}\int_t^{t + \epsilon}\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_{\tau}, \tau) d\tau = \boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_s, s)\end{equation}

Thus we obtain

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{x}_{t + \epsilon} - \boldsymbol{x}_t = \boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_s, s) \epsilon\end{equation}

Of course, the mean value theorem for integrals is strictly valid for scalar functions and is not guaranteed for vector-valued functions, so this is called an "analogy." The problem is that the value of $s$ is unknown, so AMED's subsequent approach was to use a very small model (with almost negligible computation) to predict $s$.

AMED is a post-processing correction method based on existing diffusion models. Therefore, its effectiveness depends on how well the mean value theorem holds for the $\boldsymbol{v}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)$ model, which involves some "luck." Furthermore, AMED needs to use an Euler scheme to estimate $\boldsymbol{x}_s$ first, so its NFE is at least 2 and cannot achieve single-step generation. In contrast, the Shortcut model is more "aggressive"—it directly treats the step size as a conditional input and uses the acceleration condition \eqref{eq:cond} as a loss function. This not only avoids discussions on the feasibility of the "Mean Value Theorem" approximation but also allows the minimum NFE to be reduced to 1.

Even more cleverly, upon closer inspection, we find commonalities in their approaches. Earlier we mentioned that Shortcut directly converts $\epsilon$ into an embedding and adds it to the embedding of $t$. Isn't this equivalent to modifying $t$, just like AMED! The only difference is that AMED modifies the numerical value of $t$, while Shortcut modifies the embedding of $t$.

Summary

This article introduced a new work on diffusion models that can achieve single-step generation with a single stage of training. Its breakthrough idea is to treat the step size as a conditional input to the model and pair it with an intuitive regularization term, such that a single-step generation model can be obtained through single-stage training.