By 苏剑林 | December 11, 2015

Recap of the Previous Episode

In the first article, the author introduced the concept of "entropy" and its origins. The formula for entropy is:

$$S=-\sum_x p(x)\log p(x)\tag{1}$$

or

$$S=-\int p(x)\log p(x) dx\tag{2}$$

We also learned that entropy represents both uncertainty and the amount of information; in fact, they are the same concept.

Having discussed the concept of entropy, next is the "Maximum Entropy Principle." The Maximum Entropy Principle tells us that when we want to obtain the probability distribution of a random event, if there is not enough information to completely determine the distribution (it might be that the type of distribution is unknown, or the type is known but several parameters are undetermined), the most "conservative" approach is to choose the distribution that maximizes the entropy.

Maximum Entropy Principle

Admitting Our Ignorance

Many articles, when introducing the Maximum Entropy Principle, use the famous saying—"Don't put all your eggs in one basket"—to explain it colloquially. However, the author humbly believes this phrase does not capture the essence and doesn't well reflect the core meaning of the Maximum Entropy Principle. I believe a more appropriate explanation for the Maximum Entropy Principle is: Admit our ignorance!

How should we understand the connection between this sentence and the Maximum Entropy Principle? We already know that entropy is a measure of uncertainty; maximum entropy implies maximum uncertainty. Therefore, choosing the distribution with the maximum entropy means we have chosen the distribution about which we are most ignorant. In other words, admit our ignorance of the problem and do not deceive ourselves. We can deceive each other, but we can never deceive Nature.

For example, when tossing a coin, we generally assume the probabilities for heads and tails are equal. In this case, entropy is maximized, and we are in a state of maximum ignorance regarding the coin. If someone were very confident that the probability of heads is 60% and tails is 40%, they must have known that the coin was tampered with to make heads more likely. Therefore, that person's level of knowledge about the coin is certainly higher than ours. If we do not possess that information, then we should honestly admit our ignorance and assume the probabilities are equal, avoiding subjective guesswork (since there are too many things one could subjectively guess; if we incorrectly assumed the probability of tails was higher, it would lead to even greater losses).

Therefore, selecting the maximum entropy model signifies our honesty toward nature, and we believe that if we are honest with nature, nature will not treat us poorly. This is the philosophical significance of the Maximum Entropy Principle. Additionally, admitting our ignorance means we assume we can obtain the maximum amount of information from it, which, in a sense, also aligns with the principle of maximum economy.

Estimating Probabilities

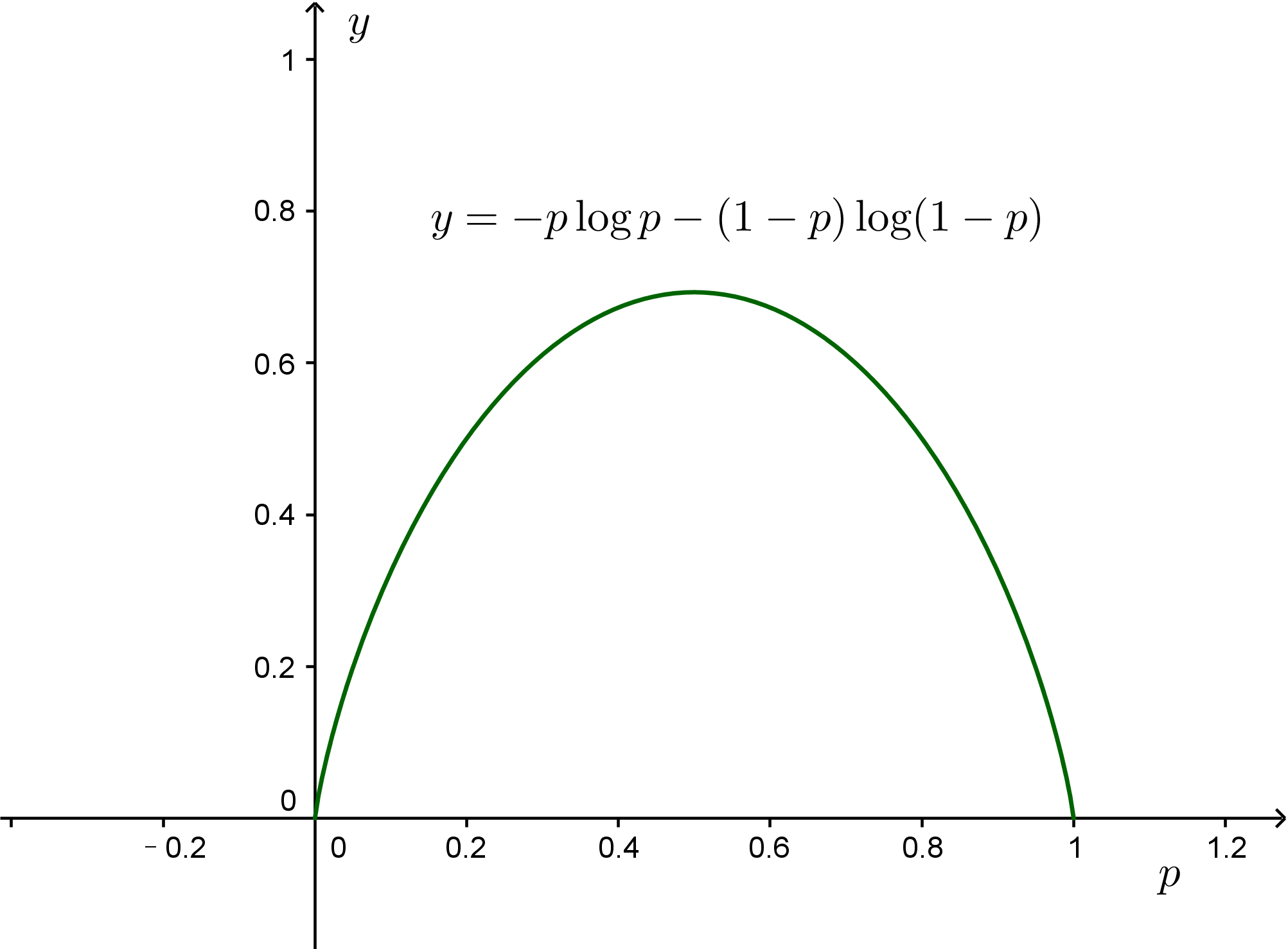

After saying so much, we haven't actually calculated anything yet, and it's clear that words alone aren't very convincing. First, let's solve the simplest problem: using the Maximum Entropy Principle to explain why we believe the probabilities of both sides are $\frac{1}{2}$ when tossing a coin. Suppose the probability of heads is $p$, then the entropy is:

$$S(p) = -p \log p - (1-p)\log (1-p)\tag{15}$$

By taking the derivative, we find that $S(p)$ is maximized when $p=\frac{1}{2}$, so we guess the probability of each side is $\frac{1}{2}$. Similarly, it can be proven that according to the Maximum Entropy Principle, when rolling a die, the probability of each face should be $\frac{1}{6}$, which is a multivariable calculus problem; if there are $n$ possibilities, the probability of each possibility should be $\frac{1}{n}$.

Maximum Entropy Principle

Note that the above are all estimates made under the assumption that we are completely ignorant. In fact, most of the time we are not that ignorant; we can derive some information based on large amounts of statistics to refine our understanding. For example, consider the following case:

A fast-food restaurant offers 3 foods: Hamburger (1), Chicken (2), Fish (3). The prices are 1 RMB, 2 RMB, and 3 RMB respectively. It is known that the average consumption per person in this shop is 1.75 RMB. Find the probability of customers buying these 3 types of food.

Here, "the average consumption in the shop is 1.75 RMB" is a result we obtained from large-scale statistics. If we assume we are completely ignorant, we would get a probability of $\frac{1}{3}$ for each food, but then the average consumption would be 2 RMB, which does not match the fact that "the average consumption is 1.75 RMB." In other words, our knowledge of the purchase situation in this shop is not complete ignorance; at least we know the "average consumption is 1.75 RMB," and this fact helps us estimate the probabilities more accurately.

Estimation Framework

Discrete Probability

These "facts" that help us estimate probabilities more accurately might be our life experiences or some kind of prior information, but regardless, they must be the result of statistics. The mathematical description is given as constraints in the form of expectations:

$$E[f(x)]=\sum_{x} p(x)f(x) = \tau\tag{16}$$

It is important to note that although we are not completely ignorant now, we still must admit our ignorance—this is ignorance subject to the knowledge of certain facts. In mathematical terms, the problem becomes finding the maximum value of equation (1) under $k$ constraints in the form of equation (16). For the fast-food example, $f(x)=x$, which means:

$$\sum_{x=1,2,3}p(x)x=1.75\tag{17}$$

Maximize $-\sum_x p(x)\log p(x)$. This type of problem is actually a constrained extremum problem in calculus, and the method is Lagrange Multipliers. By introducing a parameter $\lambda$, the original problem is equivalent to finding the extremum of the following expression:

$$-\sum_x p(x)\log p(x)-\lambda_0\left(\sum_x p(x) -1\right)-\lambda_1\left(\sum_x p(x)x -1.75\right)\tag{18}$$

In equation (18), we have introduced two constraints: the first is universal, i.e., the sum of all $p(x)$ is 1; the second is the "fact" we have recognized. Taking the derivative, we find the extremum point at $p(1) = 0.466, p(2) = 0.318, p(3)=0.216$, where entropy is maximized.

More generally, assuming there are $k$ constraints, we need to find the extremum of the following problem:

$$\begin{aligned}-\sum_x p(x)\log p(x)&-\lambda_0\left(\sum_x p(x) -1\right)-\lambda_1\left(\sum_x p(x)f_1(x) -\tau_1\right)\\

&-\dots-\lambda_k\left(\sum_x p(x)f_k(x) -\tau_k\right)\end{aligned}\tag{19}$$

Equation (19) is easily solved to give:

$$p(x)=\frac{1}{Z}\exp\left(-\sum_{i=1}^k \lambda_i f_i (x)\right)\tag{20}$$

Where $Z$ is the normalization factor, i.e.,

$$Z=\sum_x \exp\left(-\sum_{i=1}^k \lambda_i f_i (x)\right)\tag{21}$$

Substituting equation (20) back into:

$$\sum_x p(x)f_i(x) -\tau_i=0,\quad (i=1,2,\dots,k)\tag{22}$$

allows us to solve for each unknown $\lambda_i$ (unfortunately, for general $f_i(x)$, the above equation does not have a simple solution, and even numerical solutions are not easy, which makes models related to maximum entropy relatively difficult to use).

Continuous Probability

Note that equations (19), (20), (21), and (22) are derived based on discrete probabilities. The results for continuous probabilities are similar, where equation (19) corresponds to:

$$\begin{aligned}-\int p(x)\log p(x)dx &-\lambda_0\left(\int p(x)dx -1\right)-\lambda_1\left(\int p(x)f_1(x)dx -\tau_1\right)\\

&-\dots-\lambda_k\left(\int p(x)f_k(x)dx -\tau_k\right)\end{aligned}\tag{23}$$

Finding the maximum of equation (23) is actually a variational problem. However, since no derivative terms appear, it is basically no different from ordinary differentiation. The result is still:

$$p(x)=\frac{1}{Z}\exp\left(-\sum_{i=1}^k \lambda_i f_i (x)\right)\tag{24}$$

And

$$Z=\int \exp\left(-\sum_{i=1}^k \lambda_i f_i (x)\right)dx\tag{25}$$

Similarly, we need to substitute equation (24) into:

$$\int p(x)f_i(x)dx -\tau_i=0,\quad (i=1,2,\dots,k)\tag{26}$$

to solve for each parameter $\lambda_i$.

Continuous Examples

Solving for continuous cases is sometimes easier. For instance, if there is only one constraint, $f(x)=x$, meaning we know the average value of the variable, then the probability distribution is an exponential distribution:

$$p(x)=\frac{1}{Z}\exp\left(-\lambda x\right)\tag{27}$$

The normalization factor is:

$$\int_0^{\infty} \exp\left(-\lambda x\right) dx = \frac{1}{\lambda}\tag{28}$$

So the probability distribution is:

$$p(x)=\lambda \exp\left(-\lambda x\right)\tag{29}$$

The other constraint is:

$$\tau=\int_0^{\infty} \lambda \exp\left(-\lambda x\right) x dx =\frac{1}{\lambda}\tag{30}$$

So the result is:

$$p(x)=\frac{1}{\tau} \exp\left(-\frac{x}{\tau}\right)\tag{31}$$

Furthermore, if there are two constraints, $f_1(x)=x$ and $f_2(x)=x^2$, which corresponds to knowing the mean and variance of the variable, then the probability distribution is the Normal Distribution (note, the normal distribution appears again):

$$p(x)=\frac{1}{Z}\exp\left(-\lambda_1 x-\lambda_2 x^2\right)\tag{32}$$

The normalization factor is:

$$\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \exp\left(-\lambda_1 x-\lambda_2 x^2\right) dx = \sqrt{\frac{\pi}{\lambda_2}}\exp\left(\frac{\lambda_1^2}{4\lambda_2}\right)\tag{33}$$

So the probability distribution is:

$$p(x)=\sqrt{\frac{\lambda_2}{\pi}}\exp\left(-\frac{\lambda_1^2}{4\lambda_2}\right) \exp\left(-\lambda_1 x-\lambda_2 x^2\right)\tag{34}$$

The two constraints are:

$$\begin{aligned}&\tau_1=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \sqrt{\frac{\lambda_2}{\pi}}\exp\left(-\frac{\lambda_1^2}{4\lambda_2}\right) \exp\left(-\lambda_1 x-\lambda_2 x^2\right) x dx =-\frac{\lambda_1}{2\lambda_2}\\

&\tau_2=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \sqrt{\frac{\lambda_2}{\pi}}\exp\left(-\frac{\lambda_1^2}{4\lambda_2}\right) \exp\left(-\lambda_1 x-\lambda_2 x^2\right) x^2 dx =\frac{\lambda_1^2+2 \lambda_2}{4 \lambda_2^2}

\end{aligned}\tag{35}$$

Substituting the solved results into equation (34) gives:

$$p(x)=\sqrt{\frac{1}{2\pi(\tau_2-\tau_1^2)}}\exp\left(-\frac{(x-\tau_1)^2}{2(\tau_2-\tau_1^2)}\right)\tag{36}$$

Notice that $\tau_2-\tau_1^2$ is exactly the variance, so the result is exactly the normal distribution with mean $\tau_1$ and variance $\tau_2-\tau_1^2!!$ This establishes yet another origin for the normal distribution!

< Life is short, I use Python! | “熵”不起:从熵、最大熵原理到最大熵模型(三) >