By 苏剑林 | Oct 14, 2016

It has been a month since my last update. During this month, I have spent a considerable amount of time investigating the understanding of Riemannian geometry, and I would like to share some of my insights with everyone. I remember that the "Understanding Matrices" series written by Meng Yan and the "New Understanding of Matrices" written by myself both received very positive responses from readers. This time, I have adopted the same naming convention and titled this series "Understanding Riemannian Geometry."

Ants living in a two-dimensional space

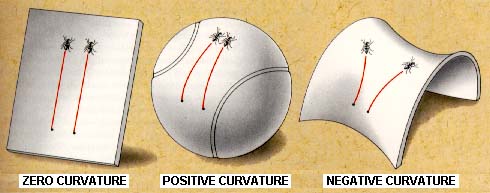

Riemannian geometry is the branch of geometry that studies intrinsic geometry. In simple terms, it considers the possibility that we live in a curved space. For example, imagine an ant living on a two-dimensional sphere. As individuals living within a curved space, we may not possess enough wisdom to "embed" our curvature into a higher-dimensional space for study. Just as the ant only knows how to crawl on the surface and cannot perceive the sphere from the perspective of a "surface in three-dimensional space" (because the sphere is its entire world), we too might be limited. Therefore, we have intrinsic geometry, which tells us that even while residing within a curved space, we can still measure lengths, areas, and volumes; we can still perform differentiation and integration; and we can even discover that our space is curved! That is to say, if the ants on the sphere have enough intelligence, they can discover that their surface is curved—much like Columbus's circumnavigation of the globe. If they travel in one direction and ultimately return to their starting point, they can conclude that the space they inhabit must be curved—and this discovery does not require any knowledge of three-dimensional space.

That being said, you will likely not see the above perspective in a standard Riemannian geometry textbook (we are using the English version of Riemannian Geometry by Manfredo P. do Carmo)—except, perhaps, for a brief mention in the preface. What you will encounter instead is a plethora of concepts like "manifolds," "homeomorphisms," "tangent bundles," "metrics," "connections," "exterior derivatives," and so on, all of which seem bewildering at first glance. After a semester of intense study, one might feel as though they are studying abstract functional analysis (Riemannian functional analysis?), completely losing any "geometric flavor." Some might even wonder: are we really studying geometry?

In addition to the lack of geometric intuition, many concepts are introduced by skipping their actual geometric background in favor of purely abstract definitions. For instance, regarding the metric, it is often said that an inner product is introduced into the tangent space to obtain the metric, and then the inner product of vectors in the tangent space can be represented by that metric. While this seems clear on the surface, many students at this stage have not even fully grasped what a tangent space is. Even if they have, they may still be confused: what is this thing, and why must we do it this way?

Certainly, abstraction has its benefits; once abstract concepts are mastered, they can often be used to solve a broad class of problems. However, this is, after all, a geometry course, and we should have some intuitive elements included to ensure that meticulous and rigorous mathematical concepts do not hinder our thinking. Intuition may not be the ultimate goal of mathematics, but it is often the source of inspiration.

Georg Friedrich Bernhard Riemann

In this article, I attempt a geometric path to elucidate some of the more important concepts in Riemannian geometry. This is not a path intended for absolute beginners. For instance, we will quickly move to calculating geodesics using the calculus of variations, which might be too demanding for a basic introduction. However, upon further consideration, readers may find that this is a path with a "strong geometric flavor"—here, there are no manifolds, no exterior derivatives, and no tensors. In search of ideas and inspiration, I specifically consulted the original paper on geometry in The Collected Works of Riemann—since it is Riemannian geometry, how could one not read Riemann's own work? I discovered that the narrative style Riemann originally used shares similarities with this article; for example, he also proceeded quickly from the metric to derive the geodesic equations via variational methods, then expanded into other discussions. It is clear that the variational method is clean and decisive, and it is well worth learning.

For readers who pursue rigor, it should be pointed out that we are actually only discussing "torsion-free geometry" (i.e., assuming the torsion is zero). The Riemannian geometry used in general relativity is also torsion-free. Torsion-free essentially means that the space is locally equivalent to flat space everywhere. This form of geometry is quite practical; even if one wishes to deeply understand geometry with torsion, a profound understanding of torsion-free geometry is a prerequisite.

This series has referenced several books related to Riemannian geometry and general relativity that I own, including:

Differential Geometry (Peng Jiagui, Chen Qing)

The Collected Works of Riemann, Vol. 1 (Higher Education Press)

Gravitation (The "Bible" of gravity by Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler (MTW), which contains a wealth of calculation examples)

The Classical Theory of Fields (Landau)

Gravitation and Spacetime

The Feynman Lectures on Physics (The world-renowned physics textbooks)

Feynman Lectures on Gravitation (Feynman's general relativity course)

Modern Geometry—Methods and Applications, Vol. 1: The Geometry of Surfaces, Transformation Groups, and Fields

Readers may also consult the works above to aid their understanding. Finally, to repeat once more, this series of articles is unlikely to serve as a standalone Riemannian geometry tutorial; at most, it is a geometric supplement to existing Riemannian geometry textbooks. For more in-depth content, standard textbooks are still required. I am simply attempting to interpret the geometric meaning of some basic content and provide a thread to connect them.

< [Chinese Word Segmentation Series] 5. Unsupervised Word Segmentation Based on Language Models

|

[Understanding Riemannian Geometry] 2. From the Pythagorean Theorem to the Riemannian Metric >