RNN Solving Two-Species Competition Model

By 苏剑林 | June 23, 2018

I had initially resolved to stop playing with RNNs, but while thinking last week, I suddenly realized that RNNs actually correspond to the numerical solutions of ODEs (Ordinary Differential Equations). This provided a line of thought for something I have always wanted to do—using deep learning to solve pure mathematical problems. In fact, this is an quite interesting and useful result, so I will introduce it. Incidentally, this article also involves writing your own RNN from scratch, so it can serve as a simple tutorial for writing custom RNN layers.

Note: This article is not an introduction to the recent trending paper "Neural ODEs" (though there are some connections).

As is well known, RNN stands for "Recurrent Neural Network." Unlike CNNs, RNN refers to a general category of models rather than a single specific model. Simply put, as long as the input is a sequence of vectors $(\boldsymbol{x}_1, \boldsymbol{x}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_T)$ and the output is another sequence of vectors $(\boldsymbol{y}_1, \boldsymbol{y}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{y}_T)$ that satisfy the following recursive relationship:

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{y}_t = f(\boldsymbol{y}_{t-1}, \boldsymbol{x}_t, t) \label{eq:rnn-basic} \end{equation}it can be called an RNN. Because of this, primitive vanilla RNNs, as well as improved models like GRU, LSTM, and SRU, are all called RNNs because they can all be seen as special cases of the above equation. There are even some concepts that seem unrelated to RNNs, such as the calculation of the CRF denominator introduced not long ago, which is actually a simple RNN.

Simply put, an RNN is essentially a recursive calculation.

Here we first introduce how to use Keras to quickly and easily write a custom RNN.

In fact, whether in Keras or pure TensorFlow, defining your own RNN is not very complicated. In Keras, you only need to write the recursive function for each step; in TensorFlow, it is slightly more complex as you need to encapsulate the recursive function for each step as an RNNCell class. Below we demonstrate the implementation of the most basic RNN using Keras:

The code is very simple:

from keras.layers import Layer

import keras.backend as K

class My_RNN(Layer):

def __init__(self, output_dim, **kwargs):

self.output_dim = output_dim # Output dimension

super(My_RNN, self).__init__(**kwargs)

def build(self, input_shape): # Define weights

self.W1 = self.add_weight(name='W1',

shape=(self.output_dim, self.output_dim),

initializer='glorot_uniform',

trainable=True)

self.W2 = self.add_weight(name='W2',

shape=(input_shape[-1], self.output_dim),

initializer='glorot_uniform',

trainable=True)

self.b = self.add_weight(name='b',

shape=(self.output_dim,),

initializer='zeros',

trainable=True)

super(My_RNN, self).build(input_shape)

def step_do(self, step_in, states): # Definition of recursion

yt_1 = states[0] # States is a list

yt = K.tanh(K.dot(yt_1, self.W1) + K.dot(step_in, self.W2) + self.b)

return yt, [yt] # Returns output and new states

def call(self, inputs): # Definition of logic

init_states = [K.zeros((K.shape(inputs)[0], self.output_dim))] # Initial state

outputs = K.rnn(self.step_do, inputs, init_states) # Iteration using the built-in K.rnn

return outputs[1] # outputs[1] is the sequence of outputs, outputs[2] is the final state

def compute_output_shape(self, input_shape):

return (input_shape[0], input_shape[1], self.output_dim)As you can see, although there are many lines of code, most of them are fixed-format statements. What truly defines the RNN is the step_do function, which takes two inputs: step_in and states. step_in is a tensor of shape (batch_size, input_dim) representing the sample $\boldsymbol{x}_t$ at the current timestep, while states is a list representing $\boldsymbol{y}_{t-1}$ and some intermediate variables. It is particularly important to note that states is a list of tensors, not a single tensor, because multiple intermediate variables might need to be passed during recursion (for example, LSTM requires two state tensors). Finally, step_do must return $\boldsymbol{y}_t$ and the new states; this is the coding standard for the step_do step function.

The K.rnn function takes three basic parameters (there are others; please consult the official documentation). The first is the step_do function we just wrote, the second is the input time sequence, and the third is the initial state, which is consistent with the states mentioned earlier. Naturally, init_states is also a list of tensors, and by default, we typically choose zero initialization.

ODE stands for "Ordinary Differential Equation," referring here to a general system of ordinary differential equations:

\begin{equation} \dot{\boldsymbol{x}}(t) = \boldsymbol{f}\big(\boldsymbol{x}(t), t\big) \label{eq:ode-general} \end{equation}The field that studies ODEs is also often referred to as "dynamics" or "dynamical systems," because Newtonian mechanics is usually just a set of ODEs.

ODEs can generate a very rich variety of functions. For example, $e^t$ is actually the solution to $\dot{x}=x$, and $\sin t$ and $\cos t$ are both solutions to $\ddot{x}+x=0$ (with different initial conditions). In fact, I remember some tutorials define the $e^t$ function directly through the differential equation $\dot{x}=x$. Besides these elementary functions, many special functions whose names we know but whose natures might be obscure—like hypergeometric functions, Legendre functions, Bessel functions—are all derived via ODEs.

In short, ODEs can produce, and have produced, all sorts of strange and wonderful functions!

There are actually very few ODEs for which an exact analytical solution can be found, so we often require numerical solutions.

The numerical solution of ODEs is a very mature discipline. We won't introduce too much here, only the most basic iterative formula proposed by the mathematician Euler:

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{x}(t + h) = \boldsymbol{x}(t) + h \boldsymbol{f}\big(\boldsymbol{x}(t), t\big) \label{eq:euler} \end{equation}where $h$ is the step size. The source of Euler's method is simple: it uses

\begin{equation} \frac{\boldsymbol{x}(t + h) - \boldsymbol{x}(t)}{h} \label{eq:derivative-approx} \end{equation}to approximate the derivative term $\dot{\boldsymbol{x}}(t)$. Given an initial condition $\boldsymbol{x}(0)$, we can follow \eqref{eq:euler} to iteratively calculate the result at each point in time.

Have you noticed the connection between \eqref{eq:euler} and \eqref{eq:rnn-basic} yet?

In \eqref{eq:rnn-basic}, $t$ is an integer variable, while in \eqref{eq:euler}, $t$ is a floating-point variable. Besides that, there seems to be no obvious difference between \eqref{eq:euler} and \eqref{eq:rnn-basic}. In fact, if we use $h$ as the unit of time in \eqref{eq:euler} and set $t=nh$, then \eqref{eq:euler} becomes:

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{x}\big((n+1)h\big) = \boldsymbol{x}(nh) + h \boldsymbol{f}\big(\boldsymbol{x}(nh), nh\big) \label{eq:discrete-ode} \end{equation}We can see that the time variable $n$ in \eqref{eq:discrete-ode} is now an integer.

Thus, we know: Euler's numerical method for ODEs \eqref{eq:euler} is actually just a special case of an RNN. From this, we might indirectly understand why RNNs have such strong fitting capabilities (especially for time-series data). We see that ODEs can produce many complex functions, and an ODE is just a special case of an RNN; therefore, an RNN can produce even more complex functions.

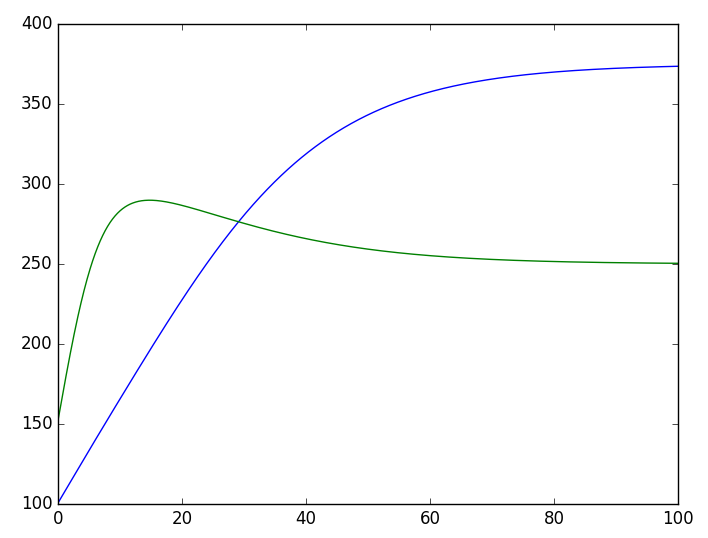

Consequently, we can write an RNN to solve an ODE. For example, using the example from "Competition Model of Two Biological Species":

\begin{equation} \left\{\begin{aligned}\frac{dx_1}{dt}=r_1 x_1\left(1-\frac{x_1}{N_1}\right)-a_1 x_1 x_2 \\ \frac{dx_2}{dt}=r_2 x_2\left(1-\frac{x_2}{N_2}\right)-a_2 x_1 x_2\end{aligned}\right. \label{eq:species-competition} \end{equation}We can write:

class ODE_RNN(Layer):

def __init__(self, steps, h, **kwargs):

self.steps = steps

self.h = h

super(ODE_RNN, self).__init__(**kwargs)

def step_do(self, step_in, states):

x = states[0]

# Parameters for biological species competition

r1, r2, N1, N2, a1, a2 = 0.1, 0.1, 500, 400, 0.0001, 0.0002

dx1 = r1 * x[:, 0] * (1 - x[:, 0] / N1) - a1 * x[:, 0] * x[:, 1]

dx2 = r2 * x[:, 1] * (1 - x[:, 1] / N2) - a2 * x[:, 0] * x[:, 1]

# Euler's method: x(t+h) = x(t) + h * f(x)

# We need to use K.stack to combine the results back into a tensor

new_x = x + self.h * K.stack([dx1, dx2], axis=1)

return new_x, [new_x]

def call(self, inputs):

# We start with the initial values and iterate 'steps' times

# The external input is not used for solving the system directly here

# so we just create a placeholder of the right length

dummy_input = K.zeros((K.shape(inputs)[0], self.steps, 1))

outputs = K.rnn(self.step_do, dummy_input, [inputs])

return outputs[1]

def compute_output_shape(self, input_shape):

return (input_shape[0], self.steps, 2)

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from keras.models import Sequential

steps, h = 1000, 0.5

M = Sequential()

M.add(ODE_RNN(steps, h, input_shape=(2,)))

# Setting initial population x1=100, x2=150

result = M.predict(np.array([[100, 150]]))[0]

plt.plot(np.arange(steps) * h, result[:, 0], label='$x_1$')

plt.plot(np.arange(steps) * h, result[:, 1], label='$x_2$')

plt.legend()

plt.show()The whole process is easy to understand, though two points should be noted. First, since the system of equations \eqref{eq:species-competition} is only two-dimensional and not easily written as matrix operations, I performed bitwise operations in the step_do function (using x[:,0], x[:,1]). If the equations had a higher dimension and could be written in matrix form, using matrix operations would be more efficient. Second, as we can see, after writing the model, simply calling predict outputs the result; no "training" is required.

RNN Solving Two-Species Competition Model

The previous section explained that the forward propagation of an RNN corresponds to Euler's method for solving an ODE. So what does backpropagation correspond to?

In practical problems, there is a class of problems called "model inference," which involves guessing the model (mechanism inference) that fits a set of experimental data. This type of problem generally consists of two steps: the first is guessing the form of the model, and the second is determining the model's parameters. Assuming this set of data can be described by an ODE, and the form of this ODE is already known, then we need to estimate the parameters within it.

If we could completely derive an analytical solution for this ODE, then this would just be a simple regression problem. But as mentioned, most ODEs have no closed-form solutions, so numerical methods are necessary. This is precisely what the backpropagation of the corresponding RNN does: forward propagation solves the ODE (the RNN's prediction process), and backpropagation naturally infers the parameters of the ODE (the RNN's training process). This is a very interesting fact: ODE parameter inference is a well-studied subject, yet in deep learning, it is just one of the most basic applications of RNNs.

Let's save the data from the previous ODE example and take only a few points to see if we can infer the original differential equation parameters. The data points are:

$\begin{array}{c|ccccccc} \hline \text{Time } t & 0 & 10 & 15 & 30 & 36 & 40 & 42\\ \hline x_1 & 100 & 165 & 197 & 280 & 305 & 318 & 324\\ \hline x_2 & 150 & 283 & 290 & 276 & 269 & 266 & 264\\ \hline \end{array}$Assuming only these limited data points are known, and assuming the form of equation \eqref{eq:species-competition}, we solve for the parameters. We modify the previous code:

class ODE_RNN(Layer):

def __init__(self, steps, h, **kwargs):

self.steps = steps

self.h = h

super(ODE_RNN, self).init(**kwargs)

def build(self, input_shape):

# We define the ODE parameters as trainable weights

self.kernel = self.add_weight(name='kernel',

shape=(6,),

initializer='ones',

trainable=True)

super(ODE_RNN, self).build(input_shape)

def step_do(self, step_in, states):

x = states[0]

# Current inferred parameters

r1, r2, N1, N2, a1, a2 = [self.kernel[i] for i in range(6)]

dx1 = r1 * x[:, 0] * (1 - x[:, 0] / N1) - a1 * x[:, 0] * x[:, 1]

dx2 = r2 * x[:, 1] * (1 - x[:, 1] / N2) - a2 * x[:, 0] * x[:, 1]

new_x = x + self.h * K.stack([dx1, dx2], axis=1)

return new_x, [new_x]

def call(self, inputs):

dummy_input = K.zeros((K.shape(inputs)[0], self.steps, 1))

outputs = K.rnn(self.step_do, dummy_input, [inputs])

return outputs[1]

# Training part (Simplified process description)

# We would use the few points we have to calculate Loss and backpropagate to update 'kernel'

# M.compile(loss='mse', optimizer='adam')

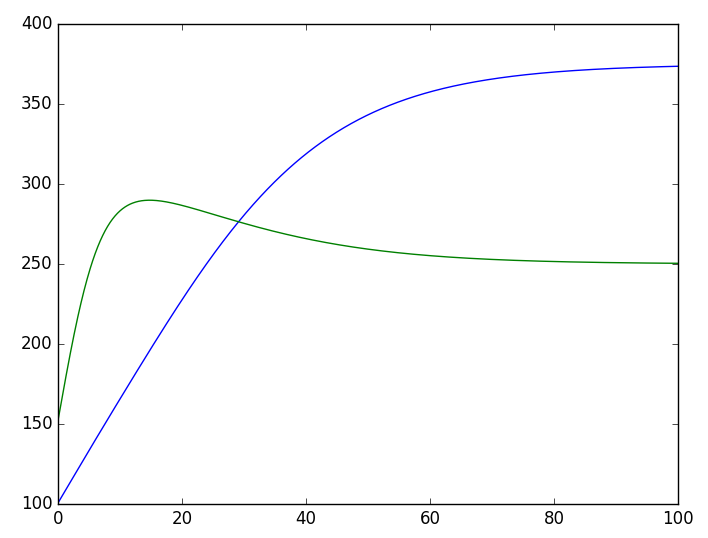

# M.fit(initial_x, historical_data_points, epochs=1000)The results can be seen in a graph:

Effect of parameter estimation using RNN (Scatter points: limited experimental data; Curves: the estimated model)

Obviously, the result is satisfactory.

This article introduced the RNN model and its custom implementation in Keras within a general framework, then revealed the connection between ODEs and RNNs. Building on this, it introduced the basic ideas of solving ODEs directly with RNNs and inferring ODE parameters with RNNs. Readers are reminded to be cautious with initialization and truncation during backpropagation in RNN models, and to choose appropriate learning rates to prevent gradient explosion (gradient vanishing is just suboptimal optimization, whereas gradient explosion leads to direct crashes; solving gradient explosion is particularly important).

In short, gradient vanishing and explosion are classic difficulties in RNNs. In fact, the introduction of models like LSTM and GRU was fundamentally to solve the gradient vanishing problem of RNNs, while gradient explosion is addressed by using tanh or sigmoid activation functions. However, if using RNNs to solve ODEs, we do not have the right to choose the activation functions (the activation function is part of the ODE itself), so we can only manage initialization and other treatments carefully. It is said that as long as initialization is done carefully, using ReLU as an activation function in ordinary RNNs is perfectly fine.