By 苏剑林 | October 22, 2018

Recently, I came across a very meaningful piece of work called "Relativistic GAN," abbreviated as RSGAN, from the paper "The relativistic discriminator: a key element missing from standard GAN." It is said that this paper even received a "like" from the GAN founder, Ian Goodfellow. This article proposes using a relative discriminator to replace the original discriminator in standard GANs, making the generator converge faster and the training more stable.

Unfortunately, the original paper primarily discusses the results from training and experimental perspectives without a more in-depth analysis, leading many to feel that it is just another GAN training trick. However, in my view, RSGAN possesses a more profound meaning; it could even be seen as having pioneered a new school of GANs. Therefore, I decided to provide a basic introduction to the RSGAN model and the connotations behind it. It should be noted that, although the results are the same, the introduction process in this article has almost no overlap with the original paper.

The "Turing Test" Thought

SGAN

SGAN is the Standard GAN. Even readers who have not researched GANs likely understand the general principle from various sources: a "counterfeiter" continuously creates fakes, attempting to fool an "appraiser"; the "appraiser" continuously improves their appraisal techniques to distinguish between real products and counterfeits. The two compete and progress together until the "appraiser" can no longer distinguish between them, at which point the "counterfeiter" retires successfully.

In modeling, this process is achieved through alternating training: fix the generator and train a discriminator (a binary classification model) to output 1 for real samples and 0 for forged samples; then fix the discriminator and train the generator to make the forged samples output 1 as much as possible. This second step does not require the participation of real samples.

The Problem

However, this modeling process seems excessively demanding for the discriminator because the discriminator operates in isolation: when training the generator, real samples are not involved. Thus, the discriminator must "remember" all the attributes of real samples to guide the generator in creating more realistic ones.

In actual life, we don't do it this way. As the saying goes, "there is no harm without comparison, and no progress without harm." Most of the time, we distinguish between genuine and counterfeit goods through comparison. For example, to identify a counterfeit bill, you might need to compare it with a genuine one; to identify a knock-off phone, you just need to compare it with the original; and so on. Similarly, if you want to make a counterfeit product more realistic, you need to keep the genuine product aside for continuous comparative improvement, rather than relying solely on the genuine product in your "memory."

Comparison makes it easier for us to identify genuine/fake items, thereby allowing us to produce better counterfeits. In the field of Artificial Intelligence, we know the famous "Turing Test," which refers to a situation where a tester communicates with a robot and a human simultaneously without knowing which is which. If the tester cannot successfully distinguish between the human and the robot, it indicates that the robot has attained human intelligence (in a particular aspect). The "Turing Test" also emphasizes the importance of comparison: if the robot and the human are indistinguishable when mixed together, the robot has succeeded.

Next, we will see that RSGAN is based on the thought of the "Turing Test": if the discriminator cannot distinguish between mixed real and fake images, then the generator has succeeded; and to generate better images, the generator also needs to rely directly on real images.

RSGAN Basic Framework

SGAN Analysis

First, let's review the standard GAN process. Let the distribution of real samples be $\tilde{p}(x)$ and the distribution of forged samples be $q(x)$. After fixing the generator, we optimize the discriminator $T(x)$:

\begin{equation}\min_{T}-\mathbb{E}_{x\sim \tilde{p}(x)}[\log \sigma(T(x))] - \mathbb{E}_{x\sim q(x)}[\log(1-\sigma(T(x)))]\label{eq:sgan-d}\end{equation}

where $\sigma$ is the sigmoid activation function. Then, fixing the discriminator, we optimize the generator $G(z)$:

\begin{equation}\min_{G}\mathbb{E}_{x=G(z),z\sim q(z)}[h(T(x))]\label{eq:sgan-g}\end{equation}

Note that we have an undetermined function $h$ here, which we will analyze shortly.

From \eqref{eq:sgan-d}, we can solve for the optimal solution of the discriminator (supplementary proof provided later):

\begin{equation}\frac{\tilde{p}(x)}{q(x)}=\frac{\sigma(T(x))}{1 - \sigma(T(x))} = e^{T(x)}\end{equation}

Substituting this into \eqref{eq:sgan-g}, we find the result to be:

\begin{equation}\min_{G}\mathbb{E}_{x=G(z),z\sim q(z)}\left[h\left(\log\frac{\tilde{p}(x)}{q(x)}\right)\right]=\min_{G}\int q(x)\left[h\left(\log\frac{\tilde{p}(x)}{q(x)}\right)\right]dx\end{equation}

Written in the form of the last equality, we can simply let $f(t)=h(\log(t))$ to see that it has the form of an $f$-divergence. That is to say, minimizing \eqref{eq:sgan-g} is equivalent to minimizing the corresponding $f$-divergence. Regarding $f$-divergences, you can refer to my previous article "Introduction to f-GAN: The Production Workshop of GAN Models." The essential requirement for $f$ in $f$-divergence is that it must be a convex function, so we only need to choose $h$ such that $h(\log(t))$ is convex. The simplest case is $h(t)=-t$, corresponding to $h(\log(t))=-\log t$ being a convex function. In this case, \eqref{eq:sgan-g} becomes:

\begin{equation}\min_{G}\mathbb{E}_{x=G(z),z\sim q(z)}[-T(x)]\end{equation}

There are many similar choices. For example, when $h(t)=-\log \sigma(t)$, then $h(\log(t))=\log(1+\frac{1}{t})$ is also a convex function (for $t > 0$), so

\begin{equation}\min_{G}\mathbb{E}_{x=G(z),z\sim q(z)}[-\log\sigma(T(x))]\end{equation}

is also a reasonable choice, which is one of the commonly used generator losses in GANs. Similarly, there is $h(t)=\log(1-\sigma(t))$, and so on.

RSGAN Objectives

Here, we directly give the optimization objectives of RSGAN. After fixing the generator, we optimize the discriminator $T(x)$:

\begin{equation}\min_{T}-\mathbb{E}_{x_r\sim \tilde{p}(x), x_f\sim q(x)}[\log \sigma(T(x_r)-T(x_f))]\label{eq:rsgan-d}\end{equation}

where $\sigma$ is the sigmoid activation function. Then, fixing the discriminator, we optimize the generator $G(z)$:

\begin{equation}\min_{G}\mathbb{E}_{x_r\sim \tilde{p}(x), x_f=G(z),z\sim q(z)}[h(T(x_f) - T(x_r))]\label{eq:rsgan-g}\end{equation}

Just like SGAN, we retain a general $h$ here, and the requirements for $h$ are consistent with the previous discussion on SGAN. The choice in the original RSGAN paper is:

\begin{equation}\min_{G}-\mathbb{E}_{x_r\sim \tilde{p}(x), x_f=G(z),z\sim q(z)}[\log\sigma(T(x_f) - T(x_r))]\end{equation}

It looks like the two terms of the SGAN discriminator were replaced with a single relative discriminator. How do the analytical results change?

Theoretical Results

Using the variational method (supplementary proof provided later), we can obtain the optimal solution for \eqref{eq:rsgan-d} as:

\begin{equation}\frac{\tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)}{\tilde{p}(x_f)q(x_r)}=\frac{\sigma(T(x_r)-T(x_f))}{\sigma(T(x_f)-T(x_r))}=e^{T(x_r)-T(x_f)}\end{equation}

Substituting this into \eqref{eq:rsgan-g}, the result is:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}&\min_{G}\mathbb{E}_{x_r\sim \tilde{p}(x), x_f=G(z),z\sim q(z)}\left[h\left(\log\frac{\tilde{p}(x_f)q(x_r)}{\tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)}\right)\right]\\

=&\min_{G}\iint \tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)\left[h\left(\log\frac{\tilde{p}(x_f)q(x_r)}{\tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)}\right)\right] dx_r dx_f\end{aligned}\label{eq:rsgan-gg}\end{equation}

This result is the essence of the entire RSGAN: it optimizes the $f$-divergence between $\tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)$ and $\tilde{p}(x_f)q(x_r)$!

What does this mean? It means if I sample a real sample $x_r$ and a forged sample $x_f$, and then swap them—treating the fake as real and the real as fake—can they still be distinguished? In other words, is there a significant difference between $\tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)$ and $\tilde{p}(x_f)q(x_r)$?

If there is no difference, it means real and fake samples are indistinguishable, training is successful. If they can still be distinguished, it means real samples are still needed to improve the forged samples. Therefore, equation \eqref{eq:rsgan-gg} is the embodiment of the "Turing Test" thought in RSGAN: once the data is shuffled, can they still be distinguished?

Model Performance Analysis

The author of the original paper also proposed RaSGAN, where 'a' stands for average, which uses the mean of the entire batch to replace a single real/fake sample. However, I don't find this to be a particularly elegant approach, and the paper also shows that the effect of RaSGAN is not always better than RSGAN, so I will not introduce it here. Interested readers can view the original paper.

As for effectiveness, the results listed in the paper show that RSGAN improves generation quality in quite a few tasks, though not universally; on average, there is a slight improvement. The author specifically pointed out that RSGAN can speed up the training of the generator. I personally experimented with it, and it is somewhat faster than SGAN and SNGAN.

My reference code: https://github.com/bojone/gan/blob/master/keras/rsgan_sn_celeba.py

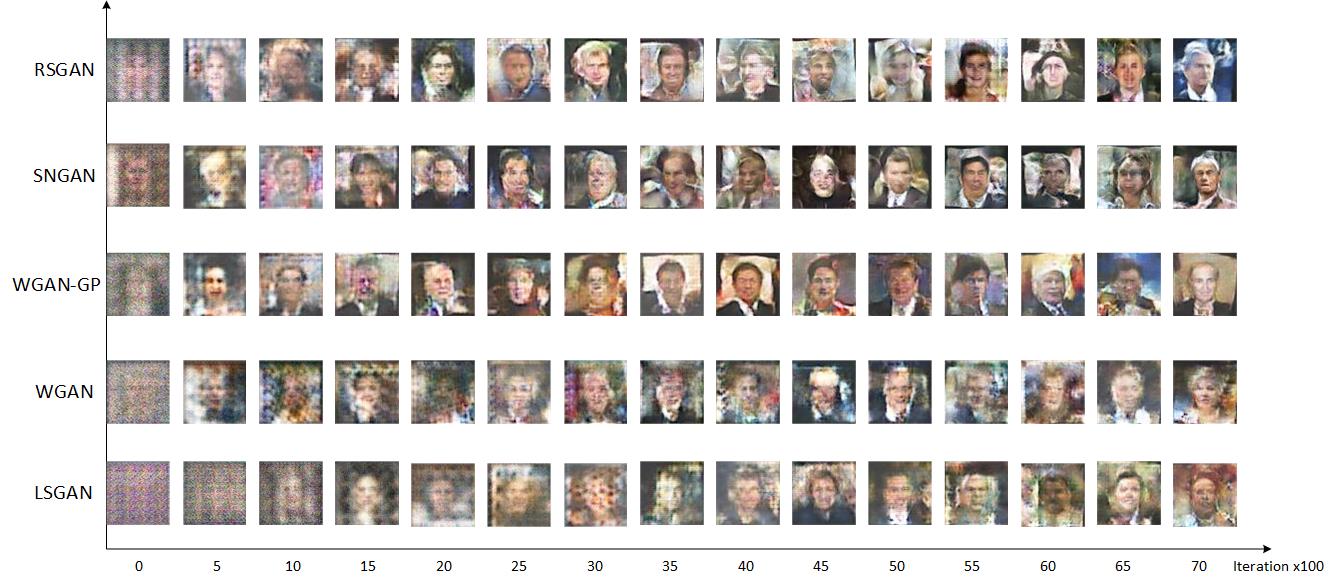

Borrowing a chart from MingtaoGuo to compare RSGAN's convergence speed:

From an intuitive perspective, RSGAN is faster because information from real samples is also used when training the generator, rather than relying solely on the "memory" of the discriminator. From a theoretical perspective, by taking the difference of $T(x_r)$ and $T(x_f)$, the discriminator only depends on their relative values, which simply improves the potential bias situation in the discriminator $T$, making gradients more stable. I even think that introducing real samples into the generator training might (though I haven't proven it carefully) improve the diversity of forged samples. Because there are various real samples for comparison, it is difficult for the model to satisfy the discriminator's relative judgment criteria if it only generates a single type of sample.

Related Discussion

Simple Summary

Overall, I believe RSGAN's improvement to GANs represents a change in thought—something even the authors of RSGAN might not have noticed.

We often say that WGAN was a major breakthrough after GAN. This is true, but that breakthrough was theoretical, whereas the thought remained the same: both were reducing the distance between two distributions. It's just that JS divergence previously had various issues, so WGAN switched to Wasserstein distance. I feel RSGAN is more of a breakthrough in thought—transforming the task into discrimination after shuffling real and fake samples—even if the results are not significantly better. (Of course, if you say that everyone ultimately pulls distributions closer, then I have nothing to say ^_^)

Some of RSGAN's improvements are easy to reproduce. However, since there isn't an improvement in every single task, some critics argue it is merely another GAN training trick. These comments are a matter of opinion, but they don't hinder my appreciation and research of this paper.

By the way, the author Alexia Jolicoeur-Martineau is a female biostatistician at Jewish General Hospital. The results in the paper were run by her using only a single GTX 1060 (source here). Suddenly, I feel proud of only having a 1060 as well... (though I have a 1060 but no papers~)

Extended Discussion

Finally, some random thoughts.

First, note that the WGAN discriminator loss itself is in the form of the difference between two terms. That is to say, the WGAN discriminator is essentially a relative discriminator, which the author believes is an important reason for WGAN's good performance.

This makes it look like WGAN and RSGAN share some common ground. But I have a further thought: can the comparison between $\tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)$ and $\tilde{p}(x_f)q(x_r)$ be completely switched to using Wasserstein distance? We know that WGAN's generator training target also has nothing to do with real samples. How can we better introduce real sample information into WGAN's generator?

Another question is, currently, the difference is only taken at the scalar level of the discriminator's final output. Could it be a difference at some hidden layer of the discriminator, followed by calculating an MSE or adding a few more neural network layers? In short, I think there is more to be done with this model...

Supplementary Proof

1. Optimal solution for \eqref{eq:sgan-d}

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}&-\mathbb{E}_{x\sim \tilde{p}(x)}[\log \sigma(T(x))] - \mathbb{E}_{x\sim q(x)}[\log(1-\sigma(T(x)))]\\

=&-\int \Big(\tilde{p}(x) \log \sigma(T(x)) + q(x) \log(1-\sigma(T(x))) \Big)dx\end{aligned}\end{equation}

Using $\delta$ for variations, which is basically the same as differentiation:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}&\delta \int \Big(\tilde{p}(x) \log \sigma(T(x)) + q(x) \log(1-\sigma(T(x))) \Big)dx\\

=& \int \left(\tilde{p}(x) \frac{\delta \sigma(T(x))}{\sigma(T(x))} + q(x) \frac{-\delta \sigma(T(x))}{1-\sigma(T(x))} \right)dx\\

=& \int \left(\tilde{p}(x) \frac{1}{\sigma(T(x))} - q(x) \frac{1}{1-\sigma(T(x))} \right)\delta \sigma(T(x)) dx

\end{aligned}\end{equation}

The extremum is reached when the variation is zero. Since $\delta \sigma(T(x))$ represents an arbitrary increment, for the above equation to be identically zero, the part inside the parentheses must be identically zero:

\begin{equation}\tilde{p}(x) \frac{1}{\sigma(T(x))} = q(x) \frac{1}{1-\sigma(T(x))}\end{equation}

2. Optimal solution for \eqref{eq:rsgan-d}

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}&-\mathbb{E}_{x_r\sim \tilde{p}(x), x_f\sim q(x)}[\log \sigma(T(x_r)-T(x_f))]\\

=&-\iint \tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)\log \sigma(T(x_r)-T(x_f)) dx_r dx_f\end{aligned}\end{equation}

Taking the variation:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}&\delta \iint \tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)\log \sigma(T(x_r)-T(x_f)) dx_r dx_f\\

=& \iint \tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)\frac{\delta \sigma(T(x_r)-T(x_f))}{\sigma(T(x_r)-T(x_f))} dx_r dx_f\quad[\text{Next, use }\sigma'(x)=\sigma(x)\sigma(-x)]\\

=& \iint \tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)\sigma(T(x_f)-T(x_r)) \times (\delta T(x_r)-\delta T(x_f)) dx_r dx_f\\

=& \iint \tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)\sigma(T(x_f)-T(x_r)) \delta T(x_r) dx_r dx_f \quad[\text{Next, swap }x_r, x_f\text{ in the second part}]\\

& \qquad - \iint \tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)\sigma(T(x_f)-T(x_r)) \delta T(x_f) dx_r dx_f\\

=& \iint \tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)\sigma(T(x_f)-T(x_r)) \delta T(x_r) dx_r dx_f \\

& \qquad - \iint \tilde{p}(x_f)q(x_r)\sigma(T(x_r)-T(x_f)) \delta T(x_r) dx_f dx_r\\

=& \iint \Big[\tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)\sigma(T(x_f)-T(x_r)) \\

& \qquad\qquad - \tilde{p}(x_f)q(x_r)\sigma(T(x_r)-T(x_f))\Big] \delta T(x_r) dx_r dx_f

\end{aligned}\end{equation}

The extremum is reached when the variation is zero, so the part within the square brackets must be zero:

\begin{equation}\tilde{p}(x_r)q(x_f)\sigma(T(x_f)-T(x_r))=\tilde{p}(x_f)q(x_r)\sigma(T(x_r)-T(x_f))\end{equation}