Optimization trajectory of the numerically solved non-saturating Dirac GAN (2D case). It can be observed that it indeed only oscillates around the equilibrium point (red dot) and does not converge.

By 苏剑林 | May 3, 2019

In the process of learning and reflecting on GANs, I found that I have not only learned an effective generative model but that it has also comprehensively promoted my understanding of various aspects of models, such as optimization and perspectives of interpretation, the significance of regularization terms, the connection between loss functions and probability distributions, probabilistic inference, and so on. GAN is not merely a "toy for making fakes"; it is a probabilistic model and inference method with profound significance.

As an ex-post summary, I feel that our understanding of GANs can be roughly divided into three stages:

1. Sample Stage: In this stage, we understand the "Discriminator-Generator" (or Counterfeiter) interpretation of GANs. We know how to write basic GAN formulas based on this principle (such as the original GAN, LSGAN), including the losses for the discriminator and generator, and can complete the training of simple GANs. At the same time, we know GANs have the ability to make images "more realistic" and can utilize this property to embed GANs into comprehensive models.

2. Distribution Stage: In this stage, we analyze GANs from the perspective of probability distributions and their divergences. Typical examples are WGAN and f-GAN. Simultaneously, we can basically understand the difficulties in training GANs, such as gradient disappearance and mode collapse. We might even have a basic understanding of variational inference, know how to write some probability divergences ourselves, and subsequently construct new GAN forms.

3. Dynamics Stage: In this stage, we begin to combine optimizers to analyze the convergence process of GANs, attempting to understand whether GANs can truly reach the theoretical equilibrium point. We further investigate how factors like GAN losses and regularization terms affect the convergence process. From this, we can propose specific training strategies to guide GAN models to reach the theoretical equilibrium point, thereby improving the performance of GANs.

In fact, not just for GANs, the understanding of general models can also be roughly divided into these three stages. Of course, readers who are fond of geometric explanations or other interpretations might disagree with the second point, feeling it is not necessary to understand through the lens of probability distributions. However, geometric and probabilistic perspectives share certain commonalities. The three stages described in this article are just a rough summary—simply put, it goes from local to global, and then to the optimizer.

This article mainly focuses on the third stage of GAN: GAN Dynamics.

In general, GAN can be expressed as a min-max process, denoted as

\[\min_G \max_D L(G,D)\]Where the step $\max_D L(G,D)$ defines a probability divergence, and the $\min_G$ step minimizes that divergence. Related discussions can be found in "Introduction to f-GAN: The Production Workshop of GAN Models" and "Interested in a GAN that doesn't use L-constraints and doesn't suffer from vanishing gradients?".

Note that theoretically, this min-max process is ordered; that is, the $\max_D$ step needs to be completed thoroughly and accurately before proceeding to $\min_G$. However, clearly, in actual GAN training, we cannot achieve this. We train D and G alternately. Ideally, we hope D and G only train once per iteration for the highest training efficiency. Such a training method corresponds to a dynamic system.

In our series "Optimization Algorithms from a Dynamic Perspective", we view gradient descent as mathematically solving a dynamic system (which is a system of ordinary differential equations, or ODEs):

\begin{equation}\dot{\boldsymbol{\theta}} = - \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} L(\boldsymbol{\theta})\end{equation}Where $L(\boldsymbol{\theta})$ is the model loss and $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ are the model parameters. If we consider randomness, it would require adding a noise term, becoming a stochastic differential equation. However, in this article, we do not consider randomness; this does not affect our analysis of local convergence. Assuming readers are familiar with this conversion, let's discuss the process corresponding to GANs.

GAN is a min-max process; in other words, one side is gradient descent and the other is gradient ascent. Assuming $\boldsymbol{\varphi}$ are the discriminator parameters and $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ are the generator parameters, the dynamic system corresponding to GAN is:

\begin{equation}\begin{pmatrix}\dot{\boldsymbol{\varphi}}\\ \dot{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\varphi}} L(\boldsymbol{\varphi},\boldsymbol{\theta})\\ - \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} L(\boldsymbol{\varphi},\boldsymbol{\theta})\end{pmatrix}\end{equation}Of course, for a more general GAN, sometimes the two $L$ functions are slightly different:

\begin{equation}\begin{pmatrix}\dot{\boldsymbol{\varphi}}\\ \dot{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\varphi}} L_1(\boldsymbol{\varphi},\boldsymbol{\theta})\\ - \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} L_2(\boldsymbol{\varphi},\boldsymbol{\theta})\end{pmatrix}\end{equation}Regardless of the type, the two terms on the right side have opposite signs, and it is precisely this difference in signs that leads to the difficulties in GAN training. We will gradually come to recognize this.

Treating the GAN optimization process as a (stochastic) dynamic system is a viewpoint already taken by several research papers. Those I have read include "The Numerics of GANs", "GANs Trained by a Two Time-Scale Update Rule Converge to a Local Nash Equilibrium", "Gradient descent GAN optimization is locally stable", and "Which Training Methods for GANs do actually Converge?". This article is merely a learning summary of the work by these pioneers.

Among these, readers might be most familiar with the second paper, as it proposed the TTUR training strategy and FID as a performance metric for GANs. The theoretical foundation of that paper also treats GAN optimization as the aforementioned stochastic dynamic system and cites a theorem from stochastic optimization to conclude that the generator and discriminator can use different learning rates (TTUR). The other papers directly view GAN optimization as deterministic dynamic systems (ODEs) and use ODE analysis methods to study GANs. Since theoretical analysis and numerical solutions for ODEs are quite mature, many ODE conclusions can be directly applied to GANs.

The reasoning and results of this article primarily refer to "Which Training Methods for GANs do actually Converge?". The main contributions of that paper are as follows:

1. Proposed the concept of Dirac GAN, which allows for a basic understanding of the behavior of GAN models quickly;

2. Provided a complete analysis of the local convergence of WGAN with zero-centered gradient penalty (also known as WGAN-div);

3. Trained 1024-resolution faces and 256-resolution LSUN generations using WGAN with zero-centered gradient penalty without needing progressive training like PGGAN.

Due to hardware limitations, the third point is hard to replicate, and the second point involves complex theoretical analysis that we won't discuss too much. Interested readers can read the original paper. This article mainly focuses on the first point: Dirac GAN.

The so-called Dirac GAN considers the performance of a GAN model when the true sample distribution consists of only a single sample point. Assume the true sample point is the zero vector $\boldsymbol{0}$, and the fake sample is $\boldsymbol{\theta}$, which also represents the parameters of the generator. The discriminator uses the simplest linear model, i.e., $D(\boldsymbol{x})=\boldsymbol{x}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi}$ (before the activation function), where $\boldsymbol{\varphi}$ represents the discriminator parameters. Dirac GAN investigates whether the fake sample can eventually converge to the true sample in such a minimal model—that is, whether $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ can eventually converge to $\boldsymbol{0}$.

However, the original paper only considered the case where the sample point is one-dimensional (i.e., $\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{\theta}, \boldsymbol{\varphi}$ are all scalars). But the cases in the later part of this article show that for some examples, a 1D Dirac GAN is insufficient to reveal convergence behavior. In general, at least a 2D Dirac GAN is needed to better analyze the asymptotic convergence of a GAN.

In the previous section, we introduced the basic concept of Dirac GAN and pointed out that it can help us quickly understand the convergence behavior of GANs. In this section, we will show how Dirac GAN achieves this by analyzing several common GANs.

Vanilla GAN, or original GAN / standard GAN, refers to the GAN originally proposed by Goodfellow. It has two forms: saturating and non-saturating. As an example, let's analyze the commonly used non-saturating form:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}&\min_D \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}\sim p(\boldsymbol{x})}[-\log D(\boldsymbol{x})]+\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}\sim q(\boldsymbol{x})}[-\log (1-D(\boldsymbol{x}))]\\ &\min_G \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{z}\sim q(\boldsymbol{z})}[-\log D(G(\boldsymbol{z}))] \end{aligned}\end{equation}Here $p(\boldsymbol{x})$ and $q(\boldsymbol{x})$ are the true and fake sample distributions respectively, and $q(\boldsymbol{z})$ is the noise distribution. $D(\boldsymbol{x})$ is activated by sigmoid. In the Dirac GAN setting, this becomes much simpler. Since the true sample has only one point at $\boldsymbol{0}$, the discriminator loss has only one term, and the discriminator can be written as $\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi}$, where $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ is the fake sample (the generator). The result is:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}&\min_{\boldsymbol{\varphi}} -\log (1-\sigma(\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi}))\\ &\min_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} -\log \sigma(\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi}) \end{aligned}\end{equation}The corresponding dynamic system is:

\begin{equation}\begin{pmatrix}\dot{\boldsymbol{\varphi}}\\ \dot{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\varphi}} \log (1-\sigma(\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi}))\\ \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} \log \sigma(\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi})\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} - \sigma(\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi}) \boldsymbol{\theta}\\ (1 - \sigma(\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi}))\boldsymbol{\varphi}\end{pmatrix}\end{equation}The equilibrium point of this dynamic system (where the right side equals zero) is $\boldsymbol{\varphi}=\boldsymbol{\theta}=\boldsymbol{0}$, meaning the fake sample becomes the true sample. However, whether the system will actually converge to the equilibrium point starting from an initial point remains unknown.

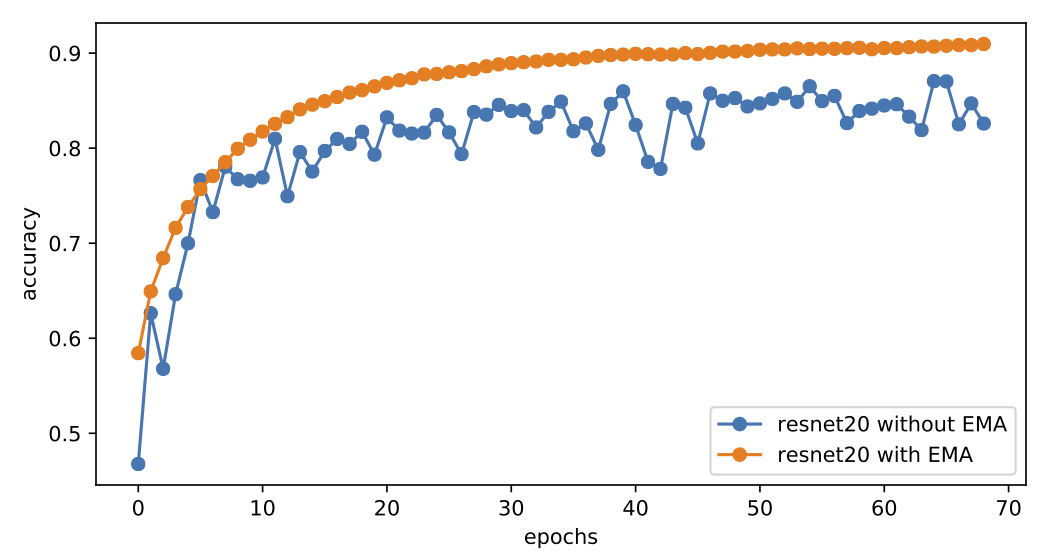

Optimization trajectory of the numerically solved non-saturating Dirac GAN (2D case). It can be observed that it indeed only oscillates around the equilibrium point (red dot) and does not converge.

To make a judgment, assume the system has already reached the vicinity of the equilibrium point, i.e., $\boldsymbol{\varphi}\approx \boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{\theta}\approx \boldsymbol{0}$. We can then use an approximate linear expansion:

\begin{equation}\begin{pmatrix}\dot{\boldsymbol{\varphi}}\\ \dot{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} - \sigma(\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi}) \boldsymbol{\theta}\\ (1 - \sigma(\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi}))\boldsymbol{\varphi}\end{pmatrix} \approx \begin{pmatrix} - \boldsymbol{\theta} / 2\\ \boldsymbol{\varphi} / 2\end{pmatrix}\end{equation}Ultimately, we approximately have:

\begin{equation}\ddot{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\approx - \boldsymbol{\theta} / 4\end{equation}Students who have studied ODEs know that this is one of the simplest linear ordinary differential equations. As long as the initial value is not $\boldsymbol{0}$, its solution is periodic, meaning the property $\boldsymbol{\theta}\to \boldsymbol{0}$ will not occur. In other words, for non-saturating Vanilla GAN, even if the model initialization is already very close to the equilibrium point, it will never converge to it but will oscillate around it. Numerical simulation results further confirm this point.

In fact, similar results appear in any form of f-GAN. That is, all GANs based on f-divergence (excluding regularization terms) suffer from the same issue: they slowly approach the vicinity of the equilibrium point and eventually just oscillate around it, unable to fully converge.

Let's repeat the logic here: we know the theoretical equilibrium point of the system is indeed what we want. However, whether we can actually reach that equilibrium point from an arbitrary starting value (equivalent to model initialization) after iterations (equivalent to training the GAN) is not obvious. At the very least, a linear expansion near the equilibrium point is needed to analyze its convergence, which is the so-called local asymptotic convergence behavior.

f-GAN has failed. What about WGAN? Can it converge to the ideal equilibrium point?

The general form of WGAN is:

\begin{equation}\min_G \max_{D, \Vert D\Vert_L\leq 1} \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}\sim p(\boldsymbol{x})}[D(\boldsymbol{x})] - \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{z}\sim q(\boldsymbol{z})}[D(G(\boldsymbol{z}))]\end{equation}Corresponding to Dirac GAN, $D(\boldsymbol{x})=\boldsymbol{x}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi}$. The constraint $\Vert D\Vert_L\leq 1$ can be ensured by $\Vert \boldsymbol{\varphi}\Vert=1$ ($\Vert\cdot\Vert$ is the $l_2$ norm). In other words, $D(\boldsymbol{x})$ with the L-constraint is $D(\boldsymbol{x})=\boldsymbol{x}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi} / \Vert\boldsymbol{\varphi}\Vert$. The WGAN corresponding to Dirac GAN is:

\begin{equation}\min_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\max_{\boldsymbol{\varphi}} \frac{-\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi}}{\Vert\boldsymbol{\varphi}\Vert}\end{equation}The corresponding dynamic system is:

\begin{equation}\begin{pmatrix}\dot{\boldsymbol{\varphi}}\\ \dot{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\varphi}} (-\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi} / \Vert \boldsymbol{\varphi}\Vert)\\ \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} (\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi} / \Vert \boldsymbol{\varphi}\Vert)\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} -\boldsymbol{\theta} / \Vert \boldsymbol{\varphi}\Vert + (\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot \boldsymbol{\varphi})\boldsymbol{\varphi} / \Vert \boldsymbol{\varphi}\Vert^3\\ \boldsymbol{\varphi} / \Vert \boldsymbol{\varphi}\Vert\end{pmatrix}\end{equation}We mainly care about whether $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ tends to $\boldsymbol{0}$. We could introduce a linear expansion similar to the previous section, but since $\Vert \boldsymbol{\varphi}\Vert$ is in the denominator, discussion becomes difficult. The most straightforward method is to solve this system numerically. The results are shown below:

The optimization trajectory of the WGAN corresponding to Dirac GAN solved numerically (2D case). It can be observed that it indeed only oscillates around the equilibrium point (red dot) and does not converge.

As can be seen, the result is still oscillation around the equilibrium point without reaching it. This result indicates that WGAN (which naturally includes spectral normalization) lacks local convergence. Even if it reaches the vicinity of the equilibrium point, it cannot land accurately on it.

(Note: A quick analysis shows that if only a 1D Dirac GAN is considered, it would be impossible to analyze WGAN in this section or GAN-QP later. This highlights the limitation of considering only the 1D case.)

You might wonder: since we already discussed WGAN, why discuss WGAN-GP?

In fact, from an optimization perspective, the previously mentioned WGAN and WGAN-GP are two different types of models. The previous WGAN refers to adding L-constraints to the discriminator beforehand (like spectral normalization) and then performing adversarial learning. Here, WGAN-GP refers to not adding L-constraints to the discriminator but instead forcing the discriminator to have L-constraints through a Gradient Penalty. There are two types of gradient penalties discussed here: the first is the "1-centered gradient penalty" proposed in "Improved Training of Wasserstein GANs", and the second is the "0-centered gradient penalty" advocated in articles like "Wasserstein Divergence for GANs" and "Which Training Methods for GANs do actually Converge?". Below we compare the different behaviors of these two gradient penalties.

The general form of gradient penalty is:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}&\min_{D} \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}\sim q(\boldsymbol{x})}[D(\boldsymbol{x})] - \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}\sim p(\boldsymbol{x})}[D(\boldsymbol{x})] + \lambda \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}\sim r(\boldsymbol{x})}\left[(\left\Vert\nabla_{\boldsymbol{x}}D(\boldsymbol{x})\right\Vert - c)^2\right]\\ &\min_{G} \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{z}\sim q(\boldsymbol{z})}[-D(G(\boldsymbol{z}))] \end{aligned}\end{equation}Where $c=0$ or $c=1$, and $r(\boldsymbol{x})$ is some derivative distribution of $p(\boldsymbol{x})$ and $q(\boldsymbol{x})$, usually taken directly as the true distribution, the fake distribution, or an interpolation between the two.

For Dirac GAN:

\begin{equation}\nabla_{\boldsymbol{x}}D(\boldsymbol{x}) = \nabla_{\boldsymbol{x}}(\boldsymbol{x}\cdot\boldsymbol{\varphi})=\boldsymbol{\varphi}\end{equation}Meaning it is independent of $\boldsymbol{x}$, so how $r(\boldsymbol{x})$ is chosen doesn't affect the result. Therefore, the Dirac GAN version of WGAN-GP is:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}&\min_{\boldsymbol{\varphi}} \boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot\boldsymbol{\varphi} + \lambda (\left\Vert \boldsymbol{\varphi}\right\Vert - c)^2\\ &\min_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} -\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot\boldsymbol{\varphi}\end{aligned}\end{equation}The corresponding dynamic system is:

\begin{equation}\begin{pmatrix}\dot{\boldsymbol{\varphi}}\\ \dot{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\varphi}} (-\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot\boldsymbol{\varphi} - \lambda (\left\Vert \boldsymbol{\varphi}\right\Vert - c)^2)\\ \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} (\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot\boldsymbol{\varphi})\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} -\boldsymbol{\theta} - 2\lambda (1 - c / \Vert \boldsymbol{\varphi}\Vert) \boldsymbol{\varphi} \\ \boldsymbol{\varphi} \end{pmatrix}\end{equation}Next, we observe whether $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ tends to $\boldsymbol{0}$ for $c=0$ and $c=1$. When $c=0$, it is just a system of linear ODEs that can be solved analytically. However, when $c=1$, it is more complex, so for simplicity, we use numerical solving:

Numerical optimization trajectory of WGAN-GP ($c=0$) corresponding to Dirac GAN (2D case). It can be observed that it can asymptotically converge to the equilibrium point (red dot).

Numerical optimization trajectory of WGAN-GP ($c=1$) corresponding to Dirac GAN (2D case). It can be observed that it indeed only oscillates around the equilibrium point (red dot) and does not converge.

The figures above show the different behaviors of gradient penalties for $c=0$ and $c=1$ under the same initial conditions (initialization), with all other parameters being equal. It can be seen that after adding the "1-centered gradient penalty," Dirac GAN does not asymptotically converge to the origin but instead converges to a circle. On the other hand, adding the "0-centered gradient penalty" achieves the goal. This indicates that the early gradient penalty terms indeed had some flaws, and the "0-centered gradient penalty" has better convergence behavior. Although the analysis above only applies to Dirac GAN, the conclusion is representative because the general proof of the superiority of the 0-centered gradient penalty has been given in "Which Training Methods for GANs do actually Converge?" and verified through experiments.

Finally, let's analyze the performance of my proposed GAN-QP. Compared to WGAN-GP, GAN-QP replaces the gradient penalty with a quadratic difference penalty and provides some supplementary proofs. The main advantage of the difference penalty compared to the gradient penalty is faster computation.

GAN-QP can take multiple forms; one basic form is:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}&\min_{D} \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_r\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_r),\boldsymbol{x}_f\sim q(\boldsymbol{x}_f)}\left[D(\boldsymbol{x}_f) - D(\boldsymbol{x}_r) + \frac{(D(\boldsymbol{x}_f) - D(\boldsymbol{x}_r))^2}{2\lambda \Vert \boldsymbol{x}_f - \boldsymbol{x}_r\Vert}\right]\\ &\min_{G} \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{z}\sim q(\boldsymbol{z})}[-D(G(\boldsymbol{z}))] \end{aligned}\end{equation}The corresponding Dirac GAN is:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}&\min_{\boldsymbol{\varphi}} \boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot\boldsymbol{\varphi} + \frac{(\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot\boldsymbol{\varphi})^2}{2\lambda \Vert \boldsymbol{\theta}\Vert}\\ &\min_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} -\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot\boldsymbol{\varphi}\end{aligned}\end{equation}The corresponding dynamic system is:

\begin{equation}\begin{pmatrix}\dot{\boldsymbol{\varphi}}\\ \dot{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\varphi}} (-\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot\boldsymbol{\varphi} - (\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot\boldsymbol{\varphi})^2 / (2\lambda \Vert \boldsymbol{\theta}\Vert))\\ \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} (\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot\boldsymbol{\varphi})\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} -\boldsymbol{\theta} - (\boldsymbol{\theta}\cdot\boldsymbol{\varphi})\boldsymbol{\theta}/(\lambda \Vert \boldsymbol{\theta}\Vert)\\ \boldsymbol{\varphi} \end{pmatrix}\end{equation}The numerical result is as follows (first image):

Numerical optimization trajectory of GAN-QP corresponding to Dirac GAN (2D case). It can be observed that it indeed only oscillates around the equilibrium point (red dot) and does not converge.

Numerical solution of a version of Dirac GAN using GAN-QP with an $L_2$ regularization term. Everything else is identical, but the addition of $L_2$ regularization indicates that appropriate $L_2$ terms can potentially induce convergence.

Unfortunately, like most GANs, GAN-QP also oscillates.

Through the analysis above, we conclude that currently, 0-centered WGAN-GP (also known as WGAN-div) has the best theoretical properties and is the only one that is locally convergent. Other GAN variants exhibit a certain degree of oscillation and cannot truly achieve asymptotic convergence. Of course, the actual situation may be much more complex; the conclusions from Dirac GAN can only provide a basic understanding to some extent.

So, if the conclusions from Dirac GAN are representative (i.e., most GANs in practice find it difficult to truly converge and instead oscillate around the equilibrium point), how should we alleviate this problem?

The first solution is to consider adding an $L_2$ regularization term to the discriminator weights of any GAN. As mentioned, 0-centered gradient penalty is very good, but unfortunately, gradient penalty is too slow. if you are unwilling to add a gradient penalty, adding an $L_2$ regularization term can be considered.

Intuitively, GANs fall into oscillation near the equilibrium point, reaching a dynamic balance (periodic solution rather than static solution). An $L_2$ regularization term forces the discriminator weights toward zero, which might break this balance, as shown in the second image above. In my own GAN experiments, adding a slight $L_2$ regularization to the discriminator makes the model convergence more stable and slightly improves effects (of course, the weight for the regularization term needs to be adjusted based on the model).

In fact, the most powerful trick to alleviate this problem is Exponential Moving Average (EMA) of the weights.

The basic concept of Weight Moving Average was introduced in "Making Keras Cooler: Intermediate Variables, Weight Sliding, and Safe Generators". Its application in GANs is not hard to understand because it can be observed that although most GANs eventually oscillate, the center of their oscillation is the equilibrium point! Therefore, the solution is simple: direct averaging of the points on the oscillation trajectory to obtain an approximate center of oscillation, which results in a solution closer to the equilibrium point (i.e., higher quality)!

The improvement brought by EMA is very significant. The figures below compare the generation results of O-GAN with and without weight moving average:

Random generation results without Weight Moving Average.

Random generation results with a Weight Moving Average decay rate of 0.999.

Random generation results with a Weight Moving Average decay rate of 0.9999.

It can be seen that Weight Moving Average brings a qualitative leap to the generation quality. The larger the decay rate, the smoother the results, but it might lose some details; a smaller decay rate preserves more details but might also keep extra noise. Currently, mainstream GANs use Weight Moving Average, typically with a decay rate of 0.999.

By the way, in ordinary supervised training models, Weight Moving Average also typically brings improvements in convergence speed. For instance, the figure below shows the training curves for a ResNet20 model on Cifar10 with and without EMA, using the Adam optimizer throughout with a fixed learning rate of 0.001 and an EMA decay rate of 0.9999:

Performance of ResNet20 trained with default Adam learning rate with and without EMA.

It can be observed that with the addition of weight moving average, the model converges to 90%+ accuracy in a very stable and fast manner, whereas without it, the accuracy oscillates around 86%. This indicates that oscillation phenomena similar to those in GANs are prevalent during deep learning training, and higher-quality models can be obtained through weight averaging.

This article primarily investigated GAN optimization issues from a dynamic perspective. Similar to other articles in this series, the optimization process is viewed as solving a system of ordinary differential equations, which is slightly more complex for GAN optimization.

The analysis utilized Dirac GAN, using the extreme simplest case of a single-point distribution to quickly understand the convergence process. The conclusion reached is that most GANs cannot truly converge to the equilibrium point but only oscillate near it. To mitigate this issue, the most effective method is Weight Moving Average, which helps both in training GANs and ordinary models.

(Code for the plots in this article: https://github.com/bojone/gan/blob/master/gan_numeric.py)