LSTM operation flow diagram

By 苏剑林 | May 28, 2019

Today, I will introduce an interesting LSTM variant: ON-LSTM, where "ON" stands for "Ordered Neurons." In other words, the neurons within this LSTM are sorted in a specific order, allowing them to express richer information. ON-LSTM comes from the paper "Ordered Neurons: Integrating Tree Structures into Recurrent Neural Networks." As the name suggests, sorting neurons in a specific way is intended to integrate hierarchical structures (tree structures) into the LSTM, thereby allowing the LSTM to automatically learn hierarchical information. This paper also has another identity: it was one of the two Best Paper award winners at ICLR 2019. This indicates that integrating hierarchical structures into neural networks (rather than purely simple omnidirectional connections) is a subject of common interest for many scholars.

I noticed ON-LSTM because of an introduction by Heart of the Machine (JiQiZhiXin), which mentioned that in addition to improving language model performance, it can even learn the syntactic structure of sentences in an unsupervised manner! It was this particular feature that deeply attracted me, and its recent recognition as an ICLR 2019 Best Paper solidified my determination to understand it. After about a week of careful study and derivation, I finally have some clarity, hence this article.

Before formally introducing ON-LSTM, I can't help but complain that the paper is written quite poorly. It takes a vivid and intuitive design and makes it exceptionally obscure and difficult to understand. The core lies in the definitions of $\tilde{f}_t$ and $\tilde{i}_t$, which were presented in the paper with almost no buildup or interpretation; even after reading them several times, they still looked like gibberish... In short, the writing style leaves much to be desired.

Usually, in the first half of an article, it is necessary to touch upon some background knowledge.

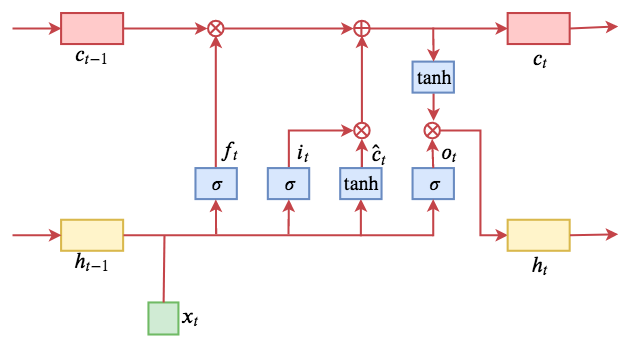

First, let's review the ordinary LSTM. Using common notation, the standard LSTM is written as:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned} f_{t} & = \sigma \left( W_{f} x_{t} + U_{f} h_{t - 1} + b_{f} \right) \\ i_{t} & = \sigma \left( W_{i} x_{t} + U_{i} h_{t - 1} + b_{i} \right) \\ o_{t} & = \sigma \left( W_{o} x_{t} + U_{o} h_{t - 1} + b_{o} \right) \\ \hat{c}_t & = \tanh \left( W_{c} x_{t} + U_{c} h_{t - 1} + b_{c} \right)\\ c_{t} & = f_{t} \circ c_{t - 1} + i_{t} \circ \hat{c}_t \\ h_{t} & = o_{t} \circ \tanh \left( c_{t} \right)\end{aligned}\label{eq:lstm}\end{equation}If you are familiar with neural networks, this structure isn't particularly mysterious. $f_t, i_t, o_t$ are three single-layer fully connected models. The inputs are the historical information $h_{t-1}$ and current information $x_t$, activated by sigmoid. Because the output of sigmoid is between 0 and 1, their meaning can be interpreted as "gates." They are called the forget gate, input gate, and output gate, respectively. However, I personally feel the name "gate" is not quite appropriate; "valve" might be more fitting.

With the gates in place, $x_t$ is transformed into $\hat{c}_t$, and then combined with the previous "gates" via the $\circ$ operation (element-wise multiplication, sometimes denoted as $\otimes$) to perform a weighted sum of $c_{t-1}$ and $\hat{c}_t$.

Below is a schematic diagram of an LSTM that I drew myself:

LSTM operation flow diagram

In common neural networks, neurons are usually unordered. For example, the forget gate $f_t$ is a vector, and the positions of its various elements follow no specific pattern. If you shuffled the positions of all vectors involved in the LSTM computation in the same way, and shuffled the weight orders accordingly, the output would simply be a reordering of the original vector (in a multi-layered case, the result might not even change). The information content remains the same, and it does not affect the subsequent network's use of it.

In other words, LSTM and ordinary neural networks do not utilize the order information of neurons. ON-LSTM, however, attempts to sort these neurons and use this order to represent specific structures, thus utilizing the order information of neurons.

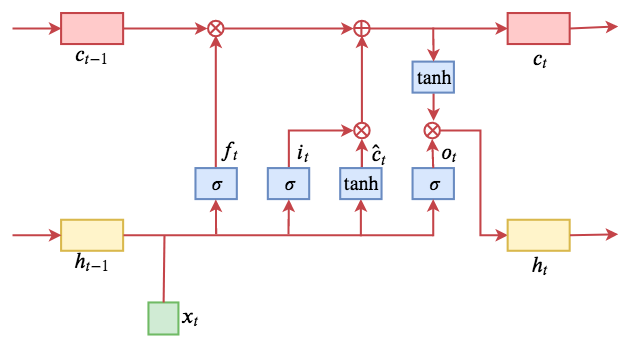

The object of study for ON-LSTM is natural language. A natural sentence can usually be represented as hierarchical structures. If these structures are manually abstracted, they are what we call syntactic information. ON-LSTM hopes that the model can naturally learn these hierarchical structures during training and parse them out (visualization) after training is complete. This utilizes the neuron order information mentioned earlier. (Previous related research: "The Principle of Minimum Entropy (III): 'Flying Elephant Across the River' - Sentence Templates and Language Structure".)

To achieve this goal, we need a concept of levels. Lower levels represent structures with smaller granularity in the language, while higher levels represent structures with coarser granularity. For example, in a Chinese sentence, "characters" can be considered the lowest level structure, followed by "words," and then phrases, clauses, etc. The higher the level and the coarser the granularity, the larger its span in the sentence.

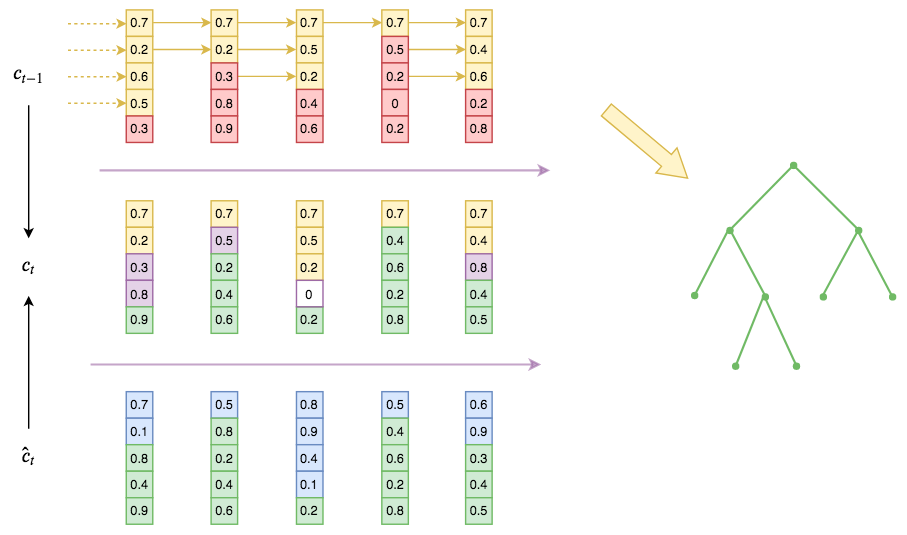

Using the illustration from the original paper:

Hierarchical structures lead to different spans for different levels, meaning different transmission distances for hierarchical information. This will ultimately guide us to represent the hierarchical structure as a matrix to integrate it into the neural network.

The final sentence, "The higher the level and the coarser the granularity, the larger its span in the sentence," might seem like a platitude, but it serves as a guiding principle for the design of ON-LSTM. First, this requires us to differentiate between high-level and low-level information in the ON-LSTM encoding. Second, it tells us that high-level information means it stays longer in the encoding range corresponding to its high level (not easily filtered out by the forget gate), while low-level information means it is more easily forgotten in its corresponding range.

With this guidance, we can begin construction. Assume that after sorting the neurons in ON-LSTM, elements in the vector $c_t$ with smaller indices represent lower-level information, while elements with larger indices represent higher-level information. Then, the gate structure and output structure of ON-LSTM remain the same as the ordinary LSTM:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned} f_{t} & = \sigma \left( W_{f} x_{t} + U_{f} h_{t - 1} + b_{f} \right) \\ i_{t} & = \sigma \left( W_{i} x_{t} + U_{i} h_{t - 1} + b_{i} \right) \\ o_{t} & = \sigma \left( W_{o} x_{t} + U_{o} h_{t - 1} + b_{o} \right) \\ \hat{c}_t & = \tanh \left( W_{c} x_{t} + U_{c} h_{t - 1} + b_{c} \right)\\ h_{t} & = o_{t} \circ \tanh \left( c_{t} \right) \end{aligned}\label{eq:update-o0}\end{equation}What differs is the mechanism for updating from $\hat{c}_t$ to $c_t$.

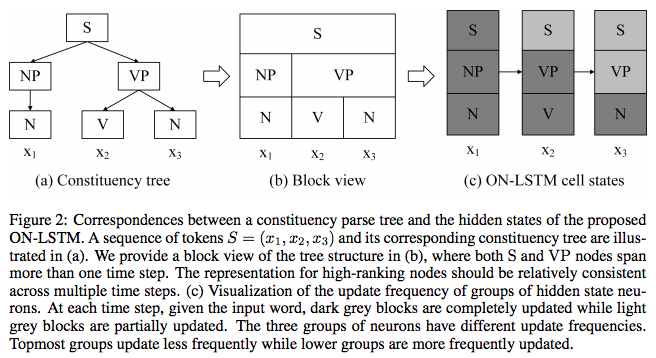

Next, initialize $c_t$ as all zeros, meaning no memory, like an empty USB drive. Then, we store historical information and current input into $c_t$ according to a certain rule (i.e., updating $c_t$). Before each update of $c_t$, we first predict two integers $d_f$ and $d_i$, representing the level of the historical information $h_{t-1}$ and the current input $x_t$, respectively:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned} d_f = F_1\left(x_t, h_{t-1}\right) \\ d_i = F_2\left(x_t, h_{t-1}\right) \end{aligned}\end{equation}As for the specific structures of $F_1, F_2$, we will add them later. Let's clarify the core logic first. This is precisely why I am dissatisfied with the original paper's writing—it starts by defining $\text{cumax}$ without explaining the idea before or after.

With $d_f$ and $d_i$, there are two possibilities:

1. $d_f \leq d_i$: This means the level of the current input $x_t$ is higher than the level of the historical record $h_{t-1}$. This implies that the information flows of both intersect, and the current input information must be integrated into levels higher than or equal to $d_f$. The method is:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned} c_t = \begin{pmatrix}\hat{c}_{t,< d_f} \\ f_{t,[d_f:d_i]}\circ c_{t-1,[d_f:d_i]} + i_{t,[d_f:d_i]}\circ \hat{c}_{t,[d_f:d_i]} \\ c_{t-1,> d_i} \end{pmatrix}\end{aligned}\label{eq:update-o1}\end{equation}This formula says that because the current input has a higher level, it affects the intersection part $[d_f, d_i]$. This part is updated using the standard LSTM update formula. The parts smaller than $d_f$ are directly overwritten by the corresponding parts of the current input $\hat{c}_t$, and the parts larger than $d_i$ keep the historical record $c_{t-1}$ unchanged.

This update formula is intuitive because we have already sorted the neurons; neurons at earlier positions store lower-level structural information. For the current input, it clearly impacts lower-level information more easily, so the "blast radius" of the current input is $[0, d_i]$ (bottom-up); it can also be understood as the storage space required by the current input being $[0, d_i]$. For the historical record, it preserves high-level information, so its "blast radius" is $[d_f, d_{\max}]$ (top-down, where $d_{\max}$ is the highest level); perhaps one could say the storage space needed by the historical info is $[d_f, d_{\max}]$. In the non-intersecting portions, they "rule their own domains," preserving their own information; in the intersecting portion, information is merged, reverting to standard LSTM.

ON-LSTM design diagram. The main idea is to sort the neurons and update them in segments.

2. $d_f > d_i$: This means the historical record $h_{t-1}$ and the current input $x_t$ do not intersect. Consequently, the range $(d_i, d_f)$ is "unclaimed," so it maintains its initial state (i.e., all zeros, which can be understood as nothing being written). For the remaining parts, the current input writes its information directly into the $[0, d_i]$ range, and historical information is written directly into the $[d_f, d_{\max}]$ range. In this case, the combination of current input and history cannot fill the entire storage space, leaving some empty capacity (the all-zero middle section).

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned} c_t = \begin{pmatrix}\hat{c}_{t,\leq d_i} \\ 0_{(d_i : d_f)} \\ c_{t-1,\geq d_f} \end{pmatrix}\end{aligned}\label{eq:update-o2}\end{equation}Where $(d_i : d_f)$ represents the range greater than $d_i$ and less than $d_f$; while the previous $[d_f : d_i]$ represents the range greater than or equal to $d_f$ and less than or equal to $d_i$.

At this point, we can understand the basic principle of ON-LSTM. After sorting neurons, it uses their position to represent the hierarchy of information levels. Then, when updating neurons, it predicts the historical level $d_f$ and the input level $d_i$ to implement segmented updates on the neurons.

ON-LSTM segmented update illustration. The numbers in the figure are randomly generated. The top is historical information, the bottom is current input, and the middle is the current integrated output. The yellow part at the top is the historical information level (master forget gate), the green part at the bottom is the input information level (master input gate). The yellow part in the middle represents directly copied historical information, the green part is directly copied input information, the purple part is intersection information fused in the LSTM manner, and the white part is the unrelated "blank territory." From the copy-transfer of historical information (the top yellow part), we can extract the corresponding hierarchical structure as shown on the right (note that the tree structure on the right is not exactly corresponding to the construction process; it is a rough illustration, and readers should focus on the intuitive perception of the images and the model rather than nitpicking the correspondence).

In this way, high-level information can potentially be preserved over a considerable distance (because the high level directly copies historical information, allowing history to be copied repeatedly without change), while low-level information may be updated with every input step (because the low level directly copies the input, which changes constantly). Thus, hierarchical structure is embedded through information classification. More simply put, this is grouped updating: higher groups transmit information further (larger span), and lower groups have smaller spans. These different spans form the hierarchical structure of the input sequence.

(Please read this paragraph repeatedly, referring back to the diagram if necessary, until you fully understand it. This paragraph defines the design blueprint of ON-LSTM.)

Now the problem is how to predict these two levels—that is, how to construct $F_1, F_2$. It’s not hard to use a model to output an integer, but such models are usually non-differentiable and cannot be integrated into the whole model for backpropagation. Thus, a better approach is to "soften" it, i.e., seek smooth approximations.

To soften the process, let's first rewrite $\eqref{eq:update-o1}$ and $\eqref{eq:update-o2}$. Introducing the notation $1_k$, which denotes a $d_{\max}$-dimensional vector with 1 at the $k$-th position and 0 elsewhere (a one-hot vector), then $\eqref{eq:update-o1}$ and $\eqref{eq:update-o2}$ can be written unified as:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}\tilde{f}_t & = \stackrel{\rightarrow}{\text{cs}}\left(1_{d_f}\right), \quad \tilde{i}_t = \stackrel{\leftarrow}{\text{cs}}\left(1_{d_i}\right) \\ \omega_t & = \tilde{f}_t \circ \tilde{i}_t \quad (\text{used to represent the intersection})\\ c_t & = \underbrace{\omega_t \circ \left(f_{t} \circ c_{t - 1} + i_{t} \circ \hat{c}_t \right)}_{\text{Intersection part}} + \underbrace{\left(\tilde{f}_t - \omega_t\right)\circ c_{t - 1}}_{\text{Part greater than }\max\left(d_f, d_i\right)} + \underbrace{\left(\tilde{i}_t - \omega_t\right)\circ \hat{c}_{t}}_{\text{Part less than }\min\left(d_f,d_i\right)} \end{aligned}\label{eq:update-o3}\end{equation}Where $\stackrel{\rightarrow}{\text{cs}}$ and $\stackrel{\leftarrow}{\text{cs}}$ are the rightward and leftward cumulative sum (cumsum) operations, respectively:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}\stackrel{\rightarrow}{\text{cs}}([x_1,x_2,\dots,x_n]) & = [x_1, x_1+x_2, \dots,x_1+x_2+\dots+x_n]\\ \stackrel{\leftarrow}{\text{cs}}([x_1,x_2,\dots,x_n]) & = [x_1+x_2+\dots+x_n,\dots,x_n+x_{n-1},x_n]\end{aligned}\end{equation}Note that the result given by $\eqref{eq:update-o3}$ is completely equivalent to the results given separately by $\eqref{eq:update-o1}$ and $\eqref{eq:update-o2}$. This is clear if you notice that $\tilde{f}_t$ gives a $d_{\max}$-dimensional vector containing 1s from the $d_f$-th position onwards and 0s elsewhere, while $\tilde{i}_t$ gives a vector with 1s from index 0 to $d_i$ and 0s elsewhere. Thus, $\omega_t = \tilde{f}_t \circ \tilde{i}_t$ results in a vector with 1s in the intersection and 0s elsewhere (if there's no intersection, it's all zeros). Therefore, the term $\omega_t \circ \left(f_{t} \circ c_{t - 1} + i_{t} \circ \hat{c}_t \right)$ handles the intersection; $(\tilde{f}_t - \omega_t)$ yields a vector with 1s from the $\max(d_f, d_i)$ position onwards, marking the range $[d_f, d_{\max}]$ of historical info minus the intersection; and $(\tilde{i}_t - \omega_t)$ yields a vector with 1s from index 0 to $\min(d_f, d_i)$, marking the range $[0, d_i]$ of current input minus the intersection.

Now, the update formula for $c_t$ is described by equation $\eqref{eq:update-o3}$. The two one-hot vectors $1_{d_f}, 1_{d_i}$ are determined by integers $d_f, d_i$, which are predicted by models $F_1, F_2$. We can simply use the models to predict $1_{d_f}$ and $1_{d_i}$ directly. Of course, even if we predict two one-hot vectors, it doesn't solve the non-differentiability of the update process. However, we can replace $1_{d_f}$ and $1_{d_i}$ with general floating-point vectors, for example:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}1_{d_f}\approx& softmax\left( W_{\tilde{f}} x_{t} + U_{\tilde{f}} h_{t - 1} + b_{\tilde{f}} \right)\\ 1_{d_i}\approx& softmax\left( W_{\tilde{i}} x_{t} + U_{\tilde{i}} h_{t - 1} + b_{\tilde{i}} \right) \end{aligned}\end{equation}In this way, we use a fully connected layer with $h_{t-1}$ and $x_t$ to predict two vectors and apply $softmax$ as an approximation of $1_{d_f}$ and $1_{d_i}$. This is completely differentiable. Substituting these into $\eqref{eq:update-o3}$, we get the $c_t$ update formula for ON-LSTM:

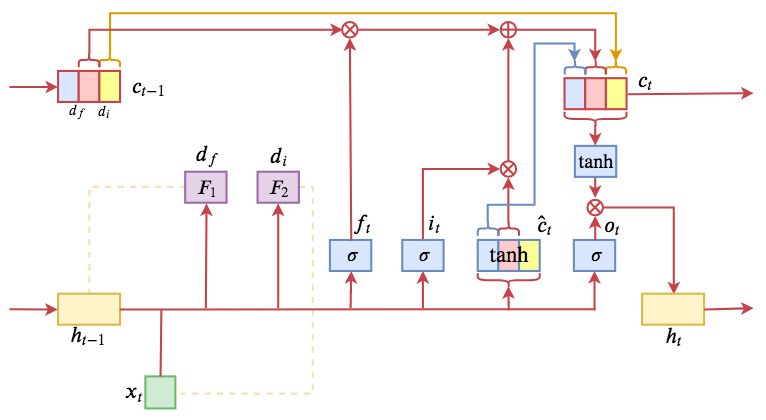

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}\tilde{f}_t & = \stackrel{\rightarrow}{\text{cs}}\left(softmax\left( W_{\tilde{f}} x_{t} + U_{\tilde{f}} h_{t - 1} + b_{\tilde{f}} \right)\right)\\ \tilde{i}_t & = \stackrel{\leftarrow}{\text{cs}}\left(softmax\left( W_{\tilde{i}} x_{t} + U_{\tilde{i}} h_{t - 1} + b_{\tilde{i}} \right)\right) \\ \omega_t & = \tilde{f}_t \circ \tilde{i}_t \quad (\text{used to represent intersection})\\ c_t & = \omega_t \circ \left(f_{t} \circ c_{t - 1} + i_{t} \circ \hat{c}_t \right) + \left(\tilde{f}_t - \omega_t\right)\circ c_{t - 1} + \left(\tilde{i}_t - \omega_t\right)\circ \hat{c}_{t} \end{aligned}\end{equation}Combining this with the remaining part (equation $\eqref{eq:update-o0}$), the complete update equations for ON-LSTM are:

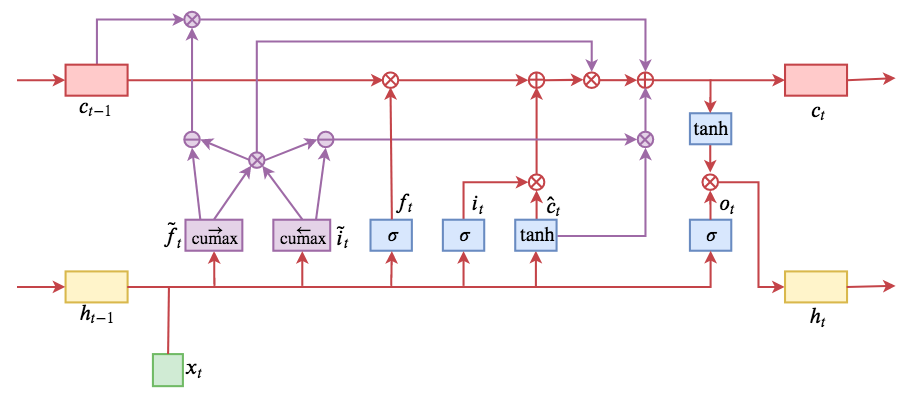

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned} f_{t} & = \sigma \left( W_{f} x_{t} + U_{f} h_{t - 1} + b_{f} \right) \\ i_{t} & = \sigma \left( W_{i} x_{t} + U_{i} h_{t - 1} + b_{i} \right) \\ o_{t} & = \sigma \left( W_{o} x_{t} + U_{o} h_{t - 1} + b_{o} \right) \\ \hat{c}_t & = \tanh \left( W_{c} x_{t} + U_{c} h_{t - 1} + b_{c} \right)\\ \tilde{f}_t & = \stackrel{\rightarrow}{\text{cs}}\left(softmax\left( W_{\tilde{f}} x_{t} + U_{\tilde{f}} h_{t - 1} + b_{\tilde{f}} \right)\right)\\ \tilde{i}_t & = \stackrel{\leftarrow}{\text{cs}}\left(softmax\left( W_{\tilde{i}} x_{t} + U_{\tilde{i}} h_{t - 1} + b_{\tilde{i}} \right)\right) \\ \omega_t & = \tilde{f}_t \circ \tilde{i}_t\\ c_t & = \omega_t \circ \left(f_{t} \circ c_{t - 1} + i_{t} \circ \hat{c}_t \right) + \left(\tilde{f}_t - \omega_t\right)\circ c_{t - 1} + \left(\tilde{i}_t - \omega_t\right)\circ \hat{c}_{t}\\ h_{t} & = o_{t} \circ \tanh \left( c_{t} \right)\end{aligned}\end{equation}The flow chart is as follows. Comparing it with the LSTM equations in $\eqref{eq:lstm}$, you can see where the main changes occur. The newly introduced $\tilde{f}_t$ and $\tilde{i}_t$ are called the "master forget gate" and "master input gate" by the authors.

ON-LSTM operation flow diagram. Transitioning from discrete segment functions to differentiable ones via cumax smoothing.

Notes:

- In the paper, $\stackrel{\rightarrow}{\text{cs}}(softmax(x))$ is shorthanded as $\text{cumax}(x)$; this is just a change in notation.

- As a sequence, $\tilde{f}_t$ is monotonically increasing, while $\tilde{i}_t$ is monotonically decreasing.

- For $\tilde{i}_t$, the paper defines it as: \[1-\text{cumax}\left( W_{\tilde{i}} x_{t} + U_{\tilde{i}} h_{t - 1} + b_{\tilde{i}} \right)\] This choice produces a similar monotonically decreasing vector; in general, there isn't much difference, but from a symmetry perspective, I believe my choice is more reasonable.

Below is a brief summary of ON-LSTM experiments, including the original author's implementation (PyTorch) and my own reproduction (Keras), followed by some of my thoughts on ON-LSTM.

Author's Implementation: https://github.com/yikangshen/Ordered-Neurons

Personal Implementation: https://github.com/bojone/on-lstm

(Given my level, there may be issues with my understanding or reproduction. If readers find any, please do not hesitate to point them out. My reproduction currently guarantees that Python 2.7 + Tensorflow 1.8 + Keras 2.24 works; other environments are not guaranteed.)

The vectors $\tilde{f}_t, \tilde{i}_t$ representing levels must undergo the $\circ$ operation with $f_t$, etc., which means their dimensions (number of neurons) must be equal. However, we know that according to needs, the number of hidden neurons in an LSTM can reach several hundred or even thousands, which implies that the number of levels described by $\tilde{f}_t, \tilde{i}_t$ would also be hundreds or thousands. In reality, the total number of levels in a sequence's hierarchical structure (if it exists) is usually not very large, meaning there's a slight contradiction here.

The authors of ON-LSTM devised a reasonable solution: assume the number of hidden neurons is $n$, which can be decomposed into $n=pq$. We can construct $\tilde{f}_t, \tilde{i}_t$ with only $p$ neurons, and then repeat each neuron in $\tilde{f}_t, \tilde{i}_t$ $q$ times sequentially to get $n$-dimensional vectors $\tilde{f}_t, \tilde{i}_t$, before performing the $\circ$ operation. For instance, if $n=6=2\times 3$, we first construct a 2-dimensional vector like $[0.1, 0.9]$, and then repeat it 3 times to get $[0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.9, 0.9, 0.9]$.

In this way, we reduce the total number of levels while also reducing the model's parameters, as $p$ can usually be small (1-2 orders of magnitude smaller than $n$). Thus, compared to ordinary LSTM, ON-LSTM does not increase parameters significantly.

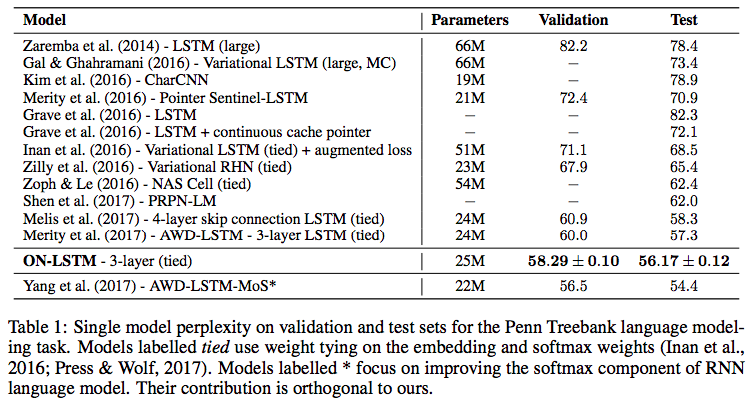

The authors conducted several experiments, including language modeling, syntactical evaluation, and logical reasoning. In many experiments, they reached state-of-the-art results, generally outperforming ordinary LSTM. This proves that the hierarchical structure information introduced by ON-LSTM is valuable. Among these, I am most familiar with the language model, so I'll include a screenshot of the results:

Language model results in the original ON-LSTM paper.

If it only outperformed ordinary LSTM in conventional language tasks, ON-LSTM wouldn't be much of a breakthrough. However, an exciting feature of ON-LSTM is its ability to extract a hierarchical tree structure from trained models (such as language models) in an unsupervised manner. The extraction idea is as follows:

First, we consider:

\begin{equation}p_f = softmax\left( W_{\tilde{f}} x_{t} + U_{\tilde{f}} h_{t - 1} + b_{\tilde{f}} \right)\end{equation}This is the result before the $\stackrel{\rightarrow}{\text{cs}}$ operation for $\tilde{f}_t$. According to our previous derivation, it is a softened version of the historical info level $d_f$. Then we can write:

\begin{equation}d_f\approx\mathop{\arg\max}_{k} p_f(k)\end{equation}Here $p_f(k)$ refers to the $k$-th element of vector $p_f$. However, because $p_f$ contains a $softmax$ (a softened operator), we might consider a "softened" version of $\arg\max$ (refer back to "On Function Smoothing: Approximating Non-Differentiable Functions"):

\begin{equation}d_f\approx \sum_{k=1}^n k\times p_f(k)=n\left(1 - \frac{1}{n}\sum_{k=1}^n \tilde{f}_t(k)\right)+1\end{equation}The second equal sign is an identity transformation (readers can prove this themselves; note that formula (15) in the original paper is incorrect). In this way, we obtain a formula for calculating the level. When $n$ is fixed, it depends directly on $\left(1 - \frac{1}{n}\sum\limits_{k=1}^n \tilde{f}_t(k)\right)$.

Therefore, we can use the sequence

\begin{equation}\left\{d_{f,t}\right\}_{t=1}^{\text{seq\_len}}=\left\{\left(1 - \frac{1}{n}\sum\limits_{k=1}^n \tilde{f}_t(k)\right)\right\}_{t=1}^{\text{seq\_len}}\end{equation}to represent the hierarchical change of the input sequence. With this sequence of levels, we can use the following greedy algorithm to extract the hierarchical structure:

Given an input sequence $\{x_t\}$ to a pre-trained ON-LSTM, output the corresponding level sequence $\{d_{f,t}\}$. Then, find the index of the maximum value in the level sequence, say $k$. Partition the input sequence into $[x_{t < k}, [x_k, x_{t > k}]]$. Then repeat the process for sub-sequences $x_{t < k}$ and $x_{t > k}$ until the length of each sub-sequence is 1.

The algorithm basically means splitting at the highest level (meaning this point contains the least historical information and has the weakest connection with preceding content, making it most likely the start of a new sub-structure) and processing recursively to obtain nested structures. The authors trained a language model using a three-layer ON-LSTM and used the $\tilde{f}_t$ from the middle layer to calculate levels. Comparing this with annotated syntactic structures, they found surprisingly high accuracy. I tried this on a Chinese corpus as well: https://github.com/bojone/on-lstm/blob/master/lm_model.py

As for the performance, since I've never done and am not familiar with syntactic analysis, I'm not sure how to evaluate it. It looks somewhat plausible but also not quite right at times, so I'll let readers evaluate for themselves.

Input: What is the color of the apple (苹果的颜色是什么)

Output:

[

[

[

'苹果',

'的'

],

[

'颜色',

'是'

]

],

'什么'

]Input: Love really requires courage (爱真的需要勇气)

Output:

[

'爱',

[

'真的',

[

'需要',

'勇气'

]

]

]

Finally, let's think about a few questions.

Is there still research value in RNNs?

Some readers might be confused—it's already the year 9102 (2019), and people are still studying RNN models? Is there still value? In recent years, pre-trained models based on Attention and Language Models like BERT and GPT have improved performance across many NLP tasks, with some articles even claiming "RNN is dead." Is this really the case? I believe RNNs are alive and well, and they won't "die" for a long time, for at least three reasons:

First, models like BERT increase computing power requirements by several orders of magnitude for just a 1-2% performance gain. This cost-effectiveness is only valuable for academic research and leaderboard chasing; in engineering, it's often not directly usable. Second, RNN models themselves possess unmatched advantages, such as easily simulating a counting function; in many sequence analysis scenarios, RNNs perform very well. Third, almost all seq2seq models (even in BERT architectures) use an RNN for the decoder because they are essentially recursive. How could RNNs disappear?

Is a unidirectional ON-LSTM enough?

Readers might wonder: you want to extract hierarchical structure, but you only use a unidirectional ON-LSTM. This means current hierarchy analysis does not depend on future input, which is clearly not entirely consistent with reality. I share this doubt, but the authors' experiments show that this approach is already good enough. Perhaps the overall structure of natural language tends to be local and unidirectional (from left to right), so unidirectional is enough for natural language.

Should bidirectional be used in general cases? If bidirectional, should it be trained using a masked language model like BERT? If bidirectional, how would you calculate the level sequence? There are no complete answers to these yet. As for whether the unsupervised extracted structure matches human understanding of hierarchy—that's also hard to say. Without supervised guidance, the neural network "understands in its own way," but fortunately, the network's "own way" seems to overlap significantly with human ways.

Why use $d_f$ instead of $d_i$ for hierarchy extraction?

Readers might be confused why we use $d_f$ instead of $d_i$ when there are two master gates. To answer this, we need to understand the meaning of $d_f$. We say $d_f$ is the level of historical information. In other words, it tells us how much history is required to make the current decision. If $d_f$ is large, it means the current decision needs almost no history, acting as the start of a new structural level, effectively severing the connection with historical input. Hierarchical structure is extracted from these breaks and connections, which is why only $d_f$ can be used.

Can this be applied to CNN or Attention?

Finally, one might wonder: can this design be applied to CNN or Attention? In other words, can we sort the neurons of CNN or Attention and integrate hierarchical information? Personally, I feel it's possible, but would require redesign. Hierarchical structure is assumed to be continuously nested—the recursiveness of RNNs naturally describes this continuity, whereas the non-recursive nature of CNNs and Attention makes it difficult to directly express such continuously nested structures.

Regardless, I think this is a subject worth thinking about. I will share any further thoughts, and I welcome readers to share theirs.

This article outlined the origins and development of ON-LSTM, a new variant of LSTM, highlighting its design principles for expressing hierarchical structures. I feel that the overall design is ingenious and interesting, well worth careful consideration.

Finally, in learning and research, the key is to have your own judgment; don't just follow others, and certainly don't believe the "clickbait" from the media. While BERT's Transformer has its advantages, the charm of RNN models like LSTM cannot be underestimated. I even suspect that one day, RNN models such as LSTM will shine even more brightly, and the Transformer will pale in comparison.

Let's wait and see.

Reproduction: please include the address of this article: https://kexue.fm/archives/6621