By 苏剑林 | June 10, 2019

Recently, when using VAE to handle some text problems, I encountered the issue of calculating the expectation of a posterior distribution in discrete form. Following the line of thought "discrete distribution + reparameterization," I eventually searched my way to Gumbel Softmax. In the process of learning about Gumbel Softmax, I reviewed all the relevant content regarding reparameterization and learned some new knowledge about gradient estimation, which I would like to record here.

This article starts introducing reparameterization from the continuous case, using the normal distribution's reparameterization as the primary example. Then, it introduces the reparameterization of discrete distributions, involving Gumbel Softmax, including some proofs and discussions. Finally, it talks about the stories behind reparameterization, mainly related to gradient estimation.

Reparameterization is actually a technique for handling objective functions in the following form of expectation:

\begin{equation}L_{\theta}=\mathbb{E}_{z\sim p_{\theta}(z)}[f(z)]\label{eq:base}\end{equation}Such objectives appear in VAEs, text GANs, and reinforcement learning (where $f(z)$ corresponds to a reward function). Therefore, delving into these fields, we frequently encounter such objective functions. Depending on the continuity of $z$, it corresponds to different forms:

\begin{equation}\int p_{\theta}(z) f(z)dz\,\,\,\text{(Continuous Case)}\qquad\qquad \sum_{z} p_{\theta}(z) f(z)\,\,\,\text{(Discrete Case)}\end{equation}Of course, in the discrete case, we prefer to replace the notation $z$ with $y$ or $c$.

To minimize $L_{\theta}$, we need to write $L_{\theta}$ out clearly. This means we must implement sampling from $p_{\theta}(z)$. However, $p_{\theta}(z)$ carries parameters $\theta$. If we sample directly, we lose the information (gradient) of $\theta$, thus making it impossible to update the parameter $\theta$. Reparameterization provides a transformation that allows us to sample effectively from $p_{\theta}(z)$ while retaining the gradient of $\theta$. (Note: In the most general form, $f(z)$ should also carry parameters $\theta$, but this does not increase the essential difficulty.)

For simplicity, let's first consider the continuous case:

\begin{equation}L_{\theta}=\int p_{\theta}(z) f(z)dz\label{eq:lianxu}\end{equation}where $p_{\theta}(z)$ is a distribution with an explicit probability density expression. A common example in Variational Autoencoders is the normal distribution $p_{\theta}(z)=\mathcal{N}\left(z;\mu_{\theta},\sigma_{\theta}^2\right)$.

We know from equation \eqref{eq:lianxu} that $L_{\theta}$ in the continuous case actually corresponds to an integral. To write $L_{\theta}$ explicitly, there are two paths: the most direct way is to precisely complete the integral \eqref{eq:lianxu} to obtain an explicit expression, but this is usually impossible. Therefore, the only way is to transform it into the sampling form \eqref{eq:base} and try to preserve the gradient of $\theta$ during the sampling process.

Reparameterization is such a technique. It assumes that sampling from the distribution $p_{\theta}(z)$ can be decomposed into two steps: (1) Sample an $\varepsilon$ from a non-parametric distribution $q(\varepsilon)$; (2) Generate $z$ through a transformation $z=g_{\theta}(\varepsilon)$. Then, equation \eqref{eq:base} becomes:

\begin{equation}L_{\theta}=\mathbb{E}_{\varepsilon\sim q(\varepsilon)}[f(g_{\theta}(\varepsilon))]\label{eq:reparam}\end{equation}Now, the sampled distribution has no parameters; all parameters have been shifted inside $f$. Therefore, we can sample several points and write them down like a normal loss.

The simplest example is the normal distribution: for a normal distribution, reparameterization changes "sampling a $z$ from $\mathcal{N}\left(z;\mu_{\theta},\sigma_{\theta}^2\right)$" into "sampling an $\varepsilon$ from $\mathcal{N}\left(\varepsilon;0, 1\right)$, and then calculating $\varepsilon\times \sigma_{\theta} + \mu_{\theta}$," so:

\begin{equation}\mathbb{E}_{z\sim \mathcal{N}\left(z;\mu_{\theta},\sigma_{\theta}^2\right)}\big[f(z)\big] = \mathbb{E}_{\varepsilon\sim \mathcal{N}\left(\varepsilon;0, 1\right)}\big[f(\varepsilon\times \sigma_{\theta} + \mu_{\theta})\big]\end{equation}How to understand why direct sampling has no gradient while it does after reparameterization? It's simple. For example, if I say to sample a number from $\mathcal{N}\left(z;\mu_{\theta},\sigma_{\theta}^2\right)$, and you tell me you sampled 5, I can't see the relationship between 5 and $\theta$ at all (the gradient can only be 0). But if I first sample a number like $0.2$ from $\mathcal{N}\left(\varepsilon;0, 1\right)$, and then calculate $0.2 \sigma_{\theta} + \mu_{\theta}$, I then know the relationship between the sampled result and $\theta$ (an effective gradient can be derived).

Let's reorganize the preceding content. Overall, reparameterization in the continuous case is relatively straightforward: we want to handle the $L_{\theta}$ in formula \eqref{eq:lianxu}. Since we cannot explicitly write out the precise integral, we need to convert it into sampling. To obtain an effective gradient during sampling, we need reparameterization.

From a mathematical essence, reparameterization is an integral transformation. Originally it was an integral with respect to $z$; after the transformation $z=g_{\theta}(\varepsilon)$, a new integral form is obtained.

To highlight the "discrete" nature, we replace the random variable $z$ with $y$. The objective function to face in the discrete case is:

\begin{equation}L_{\theta}=\mathbb{E}_{y\sim p_{\theta}(y)}[f(y)]=\sum_y p_{\theta}(y) f(y)\label{eq:lisan}\end{equation}where discrete implies that in the general case $y$ is enumerable. In other words, $p_{\theta}(y)$ is a $k$-class classification model:

\begin{equation}p_{\theta}(y)=softmax\big(o_1,o_2,\dots,o_k\big)=\frac{1}{\sum\limits_{i=1}^k e^{o_i}}\left(e^{o_1}, e^{o_2}, \dots, e^{o_k}\right)\label{eq:softmax}\end{equation}where each $o_i$ is a function of $\theta$.

When readers see the summation in \eqref{eq:lisan}, their first reaction might be "Summation? Then just sum it up, it's not like it's impossible."

Indeed, this was also my first reaction upon seeing it. Unlike the continuous case \eqref{eq:lianxu}, which would require completing an integral if tackled directly (which can be seen as a sum over infinite points), we cannot do that. However, for the discrete \eqref{eq:lisan}, it is just a sum over finite terms. Theoretically, we could indeed complete the summation before performing gradient descent.

But what if $k$ is extremely large? For example, suppose $y$ is a 100-dimensional vector where each element is either 0 or 1 (binary variables). Then the total number of different $y$ values is $2^{100}$. Calculating a sum over $2^{100}$ individual terms is computationally unacceptable. Another typical example is the decoding side of seq2seq (necessary if performing text GANs), where the total number of categories is $\|V\|^l$, where $\|V\|$ is the vocabulary size and $l$ is the sequence length. In such cases, completing the precise summation is virtually unachievable.

Therefore, we still need to return to sampling. If we can sample a few points to get an effective estimate of \eqref{eq:lisan} without losing gradient information, that would be ideal. To this end, we first introduce Gumbel Max, which provides a way to sample categories from a categorical distribution.

Assume the probabilities of each category are $p_1, p_2, \dots, p_k$. The following process provides a scheme to sample categories according to these probabilities, known as Gumbel Max:

\begin{equation}\mathop{\text{argmax}}_i \Big(\log p_i - \log(-\log \varepsilon_i)\Big)_{i=1}^k,\quad \varepsilon_i\sim U[0, 1]\end{equation}That is, first calculate the logarithm of each probability $\log p_i$, then sample $k$ random numbers $\varepsilon_1, \dots, \varepsilon_k$ from a uniform distribution $U[0, 1]$, add $-\log(-\log \varepsilon_i)$ to $\log p_i$, and finally extract the category corresponding to the maximum value.

We will prove later that this process is precisely equivalent to sampling a category according to probabilities $p_1, p_2, \dots, p_k$. In other words, in Gumbel Max, the probability of outputting $i$ is exactly $p_i$. Since the randomness has now been transferred to $U[0, 1]$, and $U[0, 1]$ contains no unknown parameters, Gumbel Max is a reparameterization process for discrete distributions.

However, we hope reparameterization doesn't lose gradient information, which Gumbel Max cannot do because $\mathop{\text{argmax}}$ is non-differentiable. To address this, further approximation is needed. First, note that in neural networks, the basic method to handle discrete inputs is to convert them into a one-hot form, including the essence of Embedding layers which is also a one-hot fully connected layer (refer to "What exactly is going on with Word Vectors and Embedding?"). Therefore, $\mathop{\text{argmax}}$ is actually $\text{onehot}(\mathop{\text{argmax}})$. We then seek a smooth approximation of $\text{onehot}(\mathop{\text{argmax}})$, which is $softmax$ (refer to "A Chat on Smoothing Functions: Differentiable Approximations of Non-differentiable Functions").

From this, we obtain a smooth-approximation version of Gumbel Max—Gumbel Softmax:

\begin{equation}softmax \Big(\big(\log p_i - \log(-\log \varepsilon_i)\big)\big/\tau\Big)_{i=1}^k,\quad \varepsilon_i\sim U[0, 1]\end{equation}where the parameter $\tau > 0$ is called the annealing parameter. The smaller it is, the closer the output is to the one-hot form (but the more severe the gradient vanishing). A small tip: if $p_i$ is the output of a softmax, i.e., in the form of \eqref{eq:softmax}, there's no need to calculate $p_i$ and then take the logarithm; you can simply replace $\log p_i$ with $o_i$:

\begin{equation}softmax \Big(\big(o_i - \log(-\log \varepsilon_i)\big)\big/\tau\Big)_{i=1}^k,\quad \varepsilon_i\sim U[0, 1]\end{equation}Proof of Gumbel Max:

The form of Gumbel Max looks a bit complex, far from as simple as the normal distribution's reparameterization. But in fact, as long as you muster the courage to look at it, even the proof is not difficult. We want to prove that the probability of Gumbel Max outputting $i$ is $p_i$. Without loss of generality, we will prove the probability of outputting 1 is $p_1$.

Note that outputting 1 means $\log p_1 - \log(-\log \varepsilon_1)$ is the largest, which means:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned} &\log p_1 - \log(-\log \varepsilon_1) > \log p_2 - \log(-\log \varepsilon_2) \\ &\log p_1 - \log(-\log \varepsilon_1) > \log p_3 - \log(-\log \varepsilon_3) \\ &\qquad \vdots\\ &\log p_1 - \log(-\log \varepsilon_1) > \log p_k - \log(-\log \varepsilon_k) \end{aligned} \end{equation}Notice that each inequality is independent. That is to say, the relationship between $\log p_1 - \log(-\log \varepsilon_1)$ and $\log p_2 - \log(-\log \varepsilon_2)$ does not affect its relationship with $\log p_3 - \log(-\log \varepsilon_3)$. Thus, we only need to analyze the probability of each inequality individually. Without loss of generality, we analyze only the first inequality, which simplifies to:

\begin{equation}\varepsilon_2 < \varepsilon_1^{p_2 / p_1}\leq 1 \end{equation}Since $\varepsilon_2\sim U[0, 1]$, the probability that $\varepsilon_2 < \varepsilon_1^{p_2 / p_1}$ is $\varepsilon_1^{p_2 / p_1}$. This is the probability that the first inequality holds given a fixed $\varepsilon_1$. Then, the probability that all inequalities hold simultaneously is:

\begin{equation}\varepsilon_1^{p_2 / p_1}\varepsilon_1^{p_3 / p_1}\dots \varepsilon_1^{p_k / p_1}=\varepsilon_1^{(p_2 + p_3 + \dots + p_k) / p_1}=\varepsilon_1^{(1/p_1)-1}\end{equation}Then, averaging over all $\varepsilon_1$ gives:

\begin{equation}\int_0^1 \varepsilon_1^{(1/p_1)-1}d\varepsilon_1 = p_1\end{equation}This is the probability that category 1 appears, which is $p_1$. Thus, we have completed the proof of the Gumbel Max sampling process.

As in the continuous case, Gumbel Softmax is used when one needs to calculate $\mathbb{E}_{y\sim p_{\theta}(y)}[f(y)]$ where the sum over $y$ cannot be completed directly. We calculate $p_{\theta}(y)$ (or $o_i$), choose a $\tau > 0$, and use Gumbel Softmax to calculate a random vector $\tilde{y}$. Substituting this into the calculation for $f(\tilde{y})$ gives a good approximation of $\mathbb{E}_{y\sim p_{\theta}(y)}[f(y)]$ while preserving gradient information.

Note that Gumbel Softmax is not an equivalent form of categorical sampling; Gumbel Max is. Gumbel Max can be seen as the limit of Gumbel Softmax as $\tau \to 0$. Therefore, when applying Gumbel Softmax, one can start with a larger $\tau$ (e.g., 1) and slowly anneal it to a number close to 0 (e.g., 0.01) to achieve better results.

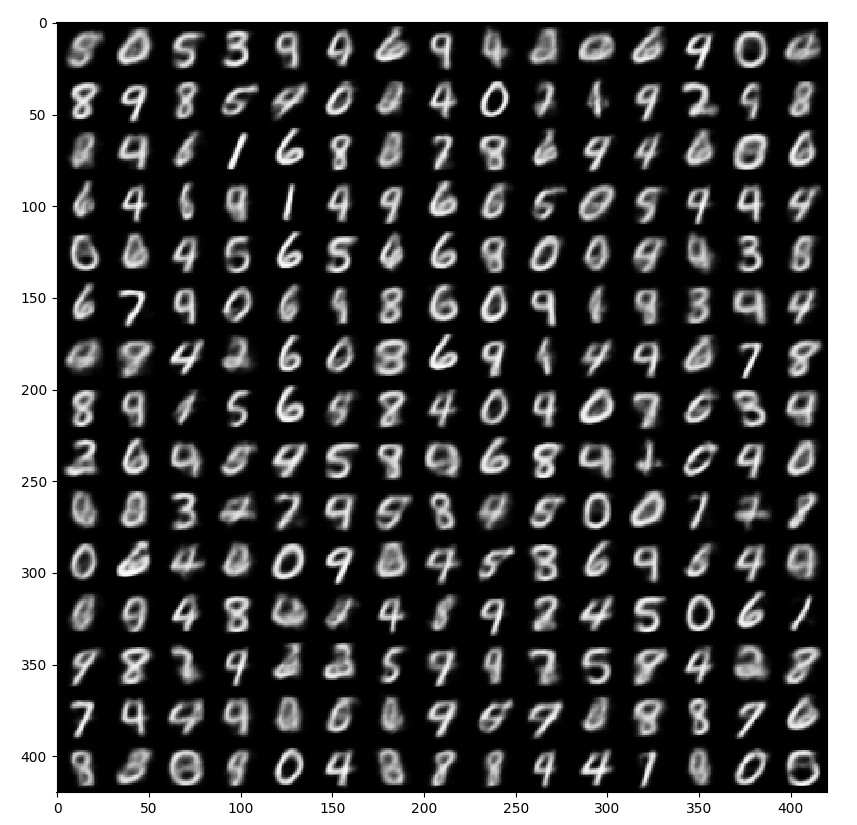

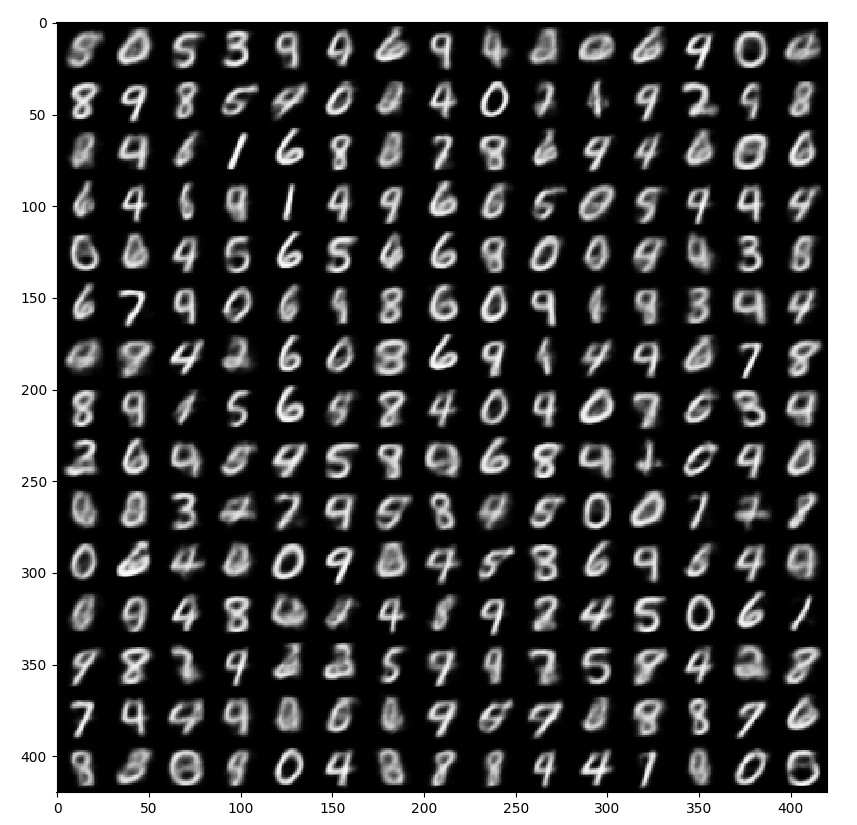

Below is an example of a discrete latent variable VAE I implemented myself:

https://github.com/bojone/vae/blob/master/vae_keras_cnn_gs.py

Effect diagram:

Discrete Latent Variable VAE Generation based on Gumbel Softmax Reparameterization

Gumbel Max has a long history, but Gumbel Softmax was first proposed and applied in the paper "Categorical Reparameterization with Gumbel-Softmax". This paper mainly explores variational inference problems where some latent variables are discrete, such as semi-supervised learning based on VAE (similar in approach to "Variational Autoencoder (IV): A One-Step Clustering Scheme"). Subsequently, in the article "GANs for Sequences of Discrete Elements with the Gumbel-softmax Distribution", Gumbel Softmax was first used for discrete sequence generation, although not for text generation but for simpler artificial character sequences.

Later, SeqGAN was proposed. Since then, text GAN models have consistently appeared in combination with reinforcement learning. Pure deep learning and gradient descent methods based on Gumbel Softmax remained relatively quiet until the emergence of RelGAN. RelGAN, a model proposed at ICLR 2019, introduced novel generator and discriminator architectures, allowing text GANs trained directly with Gumbel Softmax to significantly outperform various previous text GAN models. We will discuss RelGAN further when the opportunity arises.

This section primarily introduced Gumbel Softmax, which is a reparameterization technique for losses of the form \eqref{eq:base} in the discrete case.

Theoretically, the discrete form \eqref{eq:base} is just a finite summation and doesn't necessarily require reparameterization. However, in reality, "finite" can be a quite large number, making exhaustive summation unfeasible. Thus, it still needs decomposition into a sampling form, which requires the reparameterization technique Gumbel Softmax, derived from the smoothing of Gumbel Max.

Besides this perspective, there is an auxiliary viewpoint: Gumbel Softmax gradually approximates one-hot via $\tau \to 0$ annealing. Compared to annealing directly with the original Softmax, the difference is that original Softmax annealing can only yield a one-hot vector with 1 at the maximum position, while Gumbel Softmax has a probability of yielding a one-hot vector at a non-maximum position. This increases randomness, leading to more thorough sampling-based training.

Is that the end of the introduction to reparameterization? Far from it. Behind reparameterization lies a large family called "gradient estimators," and reparameterization is just one member of this family. Searching keywords like gradient estimator and REINFORCE at top conferences like ICLR and ICML every year yields many articles, indicating this is an ongoing research topic.

To explain the origin and development of reparameterization clearly, one must also tell some stories about gradient estimation.

Earlier, we discussed continuous and discrete reparameterization from a "loss perspective," meaning we found ways to explicitly define the loss and left the rest to the framework's automatic differentiation and optimization. In fact, even if the loss function cannot be explicitly written, it doesn't prevent us from deriving its gradient, and naturally, it doesn't prevent us from using gradient descent. For example:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}\int p_{\theta}(z) f(z)dz=&\int f(z) \frac{\partial}{\partial\theta} p_{\theta}(z) dz\\ =&\int p_{\theta}(z)\times\frac{f(z)}{p_{\theta}(z)}\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta} p_{\theta}(z) dz\\ =&\mathbb{E}_{z\sim p_{\theta}(z)}\left[\frac{f(z)}{p_{\theta}(z)}\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta} p_{\theta}(z)\right]\\ =&\mathbb{E}_{z\sim p_{\theta}(z)}\Big[f(z)\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta} \log p_{\theta}(z)\Big] \end{aligned}\label{eq:sf}\end{equation}We have now obtained an estimation formula for the gradient, known as the "SF Estimator" (Score Function Estimator). This is the most basic estimation for the original loss function. In reinforcement learning, where $z$ represents a policy, the above formula is the most fundamental policy gradient, so sometimes this estimator is also called REINFORCE. Note that re-deriving this for the discrete loss function yield the same result; in other words, the above result is universal and does not differentiate between continuous and discrete variables. Now we can directly sample points from $p_{\theta}(z)$ to estimate the value of \eqref{eq:sf}; we don't need to worry about the disappearance of gradients, because \eqref{eq:sf} itself is the gradient.

It looks beautiful—an estimation formula that applies to both continuous and discrete variables. So why do we still need reparameterization?

The main reason is that the variance of the SF estimator is too high. Formula \eqref{eq:sf} is the expectation of the function $f(z) \frac{\partial}{\partial\theta} \log p_{\theta}(z)$ under the distribution $p_{\theta}(z)$. We sample a few points for the calculation (ideally, just one point). In other words, we want to use the following approximation:

\begin{equation}\mathbb{E}_{z\sim p_{\theta}(z)}\Big[f(z) \frac{\partial}{\partial\theta} \log p_{\theta}(z)\Big]\approx f(\tilde{z}) \frac{\partial}{\partial\theta} \log p_{\theta}(\tilde{z}),\quad \tilde{z}\sim p_{\theta}(z)\end{equation}Then the problem arises: such a gradient estimate has very high variance.

What does high variance mean, and what is its impact? Take a simple example: suppose $\alpha = avg([4, 5, 6]) = avg([0, 5, 10])$. That is, our target $\alpha$ is the average of three numbers. These three numbers are either $\{4, 5, 6\}$ or $\{0, 5, 10\}$. In the case of a precise estimate, both are equivalent. But what if we can only randomly pick one number from each set? In the first group, we might pick 4, which is not bad—only 1 away from the true value 5. However, in the second group, we might pick 0, which is much further from the true value 5. That is, if only picking one randomly, the fluctuation (variance) of the second group's estimate is much larger. Similarly, the variance of the gradient estimated by SF is high, leading to significant instability during gradient descent optimization, making it very prone to failure.

From a formal standpoint, equation \eqref{eq:sf} is very elegant—the form itself is not complex, it applies to both discrete and continuous variables, and it places no special requirements on $f$ (conversely, reparameterization requires $f$ to be differentiable, but in scenarios such as reinforcement learning where $f(z)$ corresponds to a reward function, it's hard to ensure smoothness and differentiability). Therefore, many papers explore variance reduction techniques based on formula \eqref{eq:sf}. The paper "Categorical Reparameterization with Gumbel-Softmax" lists several, and there have been new developments in recent years. In short, searching for keywords like gradient estimator and REINFORCE will yield many articles.

Reparameterization is another variance reduction technique. To see this, we write the gradient expression for \eqref{eq:reparam} after reparameterization:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}\mathbb{E}_{\varepsilon\sim q(\varepsilon)}[f(g_{\theta}(\varepsilon))]=&\mathbb{E}_{\varepsilon\sim q(\varepsilon)}\left[\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}f(g_{\theta}(\varepsilon))\right]\\ =&\mathbb{E}_{\varepsilon\sim q(\varepsilon)}\left[\frac{\partial f}{\partial g} \frac{\partial g_{\theta}(\varepsilon)}{\partial\theta}\right] \end{aligned}\end{equation}Comparing this with the SF estimator \eqref{eq:sf}, we can intuitively sense why the variance above is smaller:

1. The SF estimator includes $\log p_{\theta}(z)$. We know that for a reasonable probability distribution, $p_{\theta}(z) \to 0$ as $\|z\| \to \infty$. Taking the $\log$ causes it to go to negative infinity. In other words, the $\log p_{\theta}(z)$ term actually amplifies fluctuations at infinity, thus increasing the variance to a certain extent;

2. The SF estimator contains $f$, whereas reparameterization changes it to $\frac{\partial f}{\partial g}$. $f$ is generally a neural network, and we know that the neural network models we define are usually of order $\mathcal{O}(z)$, so we can expect their gradients to be of order $\mathcal{O}(1)$ (this is not strictly true, but generally holds in an average sense). Thus, it is relatively more stable, so the variance of $f$ is larger than the variance of $\frac{\partial f}{\partial g}$.

Given these two reasons, we can conclude that in generic cases, the variance of the gradient estimate after reparameterization is smaller than that of the SF estimator. Note that we must emphasize "generic cases." In other words, the conclusion that "reparameterization reduces the variance of the gradient estimate" is not absolutely true. The two reasons above apply to most models we encounter; if we really want to nitpick, we could always construct examples where reparameterization actually increases variance.

After a long discussion, we have essentially straightened out the story of reparameterization. A deeper understanding of the reparameterization technique is essential for better understanding VAEs and text GANs.

From the perspective of loss functions, we must distinguish between continuous and discrete cases: in the continuous case, reparameterization is a method to write the loss in sampled form without losing gradients. In the discrete case, it serves the same purpose, but the more fundamental reason is to reduce the computational cost (otherwise, exhaustive summation would work). From the perspective of gradient estimation, reparameterization is an effective means of reducing the variance of gradient estimates, while other variance reduction methods are also being studied by many scholars.

In short, it's not something you can easily ignore!