By 苏剑林 | February 07, 2020

CRF (Conditional Random Field) is a classic method for sequence labeling. It is theoretically elegant and practically effective. For readers who are not yet familiar with CRF, feel free to read my previous post "A Brief Introduction to Conditional Random Fields (CRF) (with pure Keras implementation)". After the emergence of the BERT model, much work has explored using BERT+CRF for sequence labeling tasks. However, many experimental results (such as those in the paper "BERT Meets Chinese Word Segmentation") show that for both Chinese word segmentation and named entity recognition, BERT+CRF does not seem to bring any significant improvement compared to a simple BERT+Softmax approach. This differs from the behavior observed in traditional BiLSTM+CRF or CNN+CRF models.

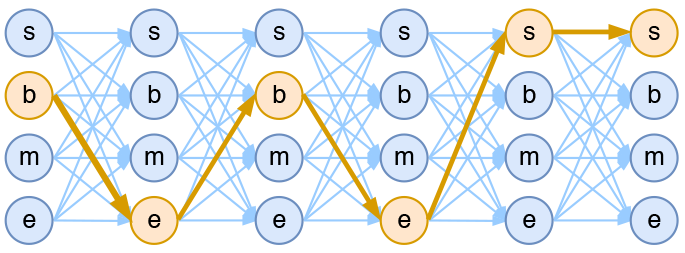

Schematic of a 4-tag word segmentation model based on CRF

Over the past couple of days, I added a Chinese word segmentation example using CRF to bert4keras (task_sequence_labeling_cws_crf.py). During debugging, I discovered that the CRF layer might suffer from insufficient learning. Further comparative experiments suggested that this might be the primary reason why CRF shows little improvement in BERT. I am recording the analysis process here to share with everyone.

The Terrible Transition Matrix

Since I am using my own implementation of the CRF layer, to ensure there were no implementation errors, I first observed the transition matrix after running the BERT+CRF experiment (using the BERT-base version). The approximate values were as follows:

| s | b | m | e |

| s | -0.0517 | -0.459 | -0.244 | 0.707 |

| b | -0.564 | -0.142 | 0.314 | 0.613 |

| m | 0.196 | -0.334 | -0.794 | 0.672 |

| e | 0.769 | 0.841 | -0.683 | 0.572 |

The value at the $i$-th row and $j$-th column represents the score of transferring from $i$ to $j$ (denoted as $S_{i \to j}$). Note that the absolute values of these scores are meaningless; only their relative comparisons matter. For context, this Chinese word segmentation task uses the (s, b, m, e) tagging method. If you are unfamiliar with it, you can refer to "[Chinese Word Segmentation Series] 3. Character Tagging and HMM Models".

Intuitively, however, this does not look like a well-learned transition matrix; in fact, it might even have a negative impact. For instance, looking at the first row, $S_{s \to b} = -0.459$ and $S_{s \to e} = 0.707$. This means $S_{s \to b}$ is significantly smaller than $S_{s \to e}$. According to the design of (s, b, m, e) tagging, it is possible for 's' to be followed by 'b', but impossible for it to be followed by 'e'. Thus, $S_{s \to b} < S_{s \to e}$ is clearly unreasonable. It could potentially guide the model toward invalid tag sequences. Ideally, $S_{s \to e}$ should be $-\infty$.

Such an unreasonable transition matrix initially made me worry that my CRF implementation was flawed. But after repeated checks and comparison with the official Keras implementation, I confirmed the implementation was correct. So where was the problem?

Learning Rate Imbalance

If we ignore the irrationality of this transition matrix and simply use the Viterbi algorithm for decoding/prediction based on the training results, and then evaluate it with official scripts, the F1 score is about 96.1% (on the PKU task), which is already state-of-the-art.

The fact that the transition matrix is terrible but the final result is still good indicates that the transition matrix has almost no impact on the final outcome. In what situation does the transition matrix become negligible? A possible reason is that the tag scores output by the model for each character are far larger than the values in the transition matrix and have distinct differentiation. Consequently, the transition matrix cannot influence the overall result. In other words, at this point, simply using Softmax and taking the argmax would already be very good. To confirm this, I randomly selected several sentences and observed the predicted tag distribution. I found that the highest tag score for each character was generally between 6 and 8, while the scores for other tags were usually more than 3 points lower. This is an order of magnitude larger than the values in the transition matrix, making it difficult for the transition matrix to exert influence. This confirmed my suspicion.

A good transition matrix should obviously help prediction, at least by helping us eliminate unreasonable tag transitions or ensuring no negative impact. So it is worth considering: what prevents the model from learning a good transition matrix? I suspect the answer is the learning rate.

When BERT is fine-tuned for downstream tasks after pre-training, it requires a very small learning rate (usually in the range of $10^{-5}$). Anything too large might lead to non-convergence. Although the learning rate is small, for most downstream tasks, convergence is fast; many tasks reach an optimum in just 2 to 3 epochs. Furthermore, BERT has a powerful fitting capacity, allowing it to fit the training data quite thoroughly.

What does this imply? First, we know that the tag distribution for each character is calculated directly by the BERT model, while the transition matrix is an additional component not directly related to BERT. When fine-tuning with a learning rate of $10^{-5}$, the BERT portion converges rapidly—meaning the character-level distributions are fitted quickly—and reaches a near-optimal state (high scores for target tags, wide gap from non-target tags) due to BERT's strong capability. Since the transition matrix is independent of BERT, while the character distributions converge rapidly, the transition matrix continues to "stroll along" at the $10^{-5}$ pace. Eventually, its values remain an order of magnitude lower than the character distribution scores. Moreover, once the character distributions fit the target sequence well, the transition matrix is no longer "needed" (its gradients become very small), so it almost stops updating.

Reflecting on this, a natural idea is: can we increase the learning rate of the CRF layer? I tried increasing the CRF layer's learning rate and found through multiple experiments that when the CRF learning rate is 100 times or more than the main learning rate, the transition matrix starts to become reasonable. Below is a transition matrix trained with a BERT learning rate of $10^{-5}$ and a CRF learning rate of $10^{-2}$ (i.e., 1000 times larger):

| s | b | m | e |

| s | 3.1 | 7.2.16 | -3.97 | -2.04 |

| b | -3.89 | -0.451 | 1.67 | 0.874 |

| m | -3.9 | -4.41 | 3.82 | 2.45 |

| e | 1.88 | 0.991 | -2.48 | -0.247 |

Such a transition matrix is reasonable, and its scale is correct. It has learned the correct tag transitions, such as $s \to s, b$ scoring higher than $s \to m, e$, and $b \to m, e$ scoring higher than $b \to s, b$, etc. However, even after adjusting the CRF learning rate, the results did not show a significant advantage over the unadjusted version. Ultimately, BERT's fitting power is so strong that even Softmax achieves optimal effects, meaning the transition matrix naturally contributes little additional gain.

(Note: Implementation techniques for increasing the learning rate can be found in "'Make Keras Cooler!': Layer-wise Learning Rates and Free Gradients".)

Further Experimental Analysis

The reason CRF didn't improve BERT results is that BERT's fitting power is too strong, making the transition matrix unnecessary. If we reduce BERT's fitting capability, will there be a significant difference?

In the previous experiments, we used the output of the 12th layer of BERT-base for fine-tuning. Now, we use only the output of the 1st layer to see if the adjustments bring significant improvements. The results are shown in the table below:

| Model | Main LR | CRF LR | Epoch 1 Test F1 | Best Test F1 |

| CRF-1 | $10^{-3}$ | $10^{-3}$ | 0.914 | 0.925 |

| CRF-2 | $10^{-3}$ | $10^{-2}$ | 0.929 | 0.930 |

| CRF-3 | $10^{-2}$ | $10^{-2}$ | 0.673 | 0.747 |

| Softmax | $10^{-3}$ | - | 0.899 | 0.907 |

Since we only used 1 layer of BERT, the main learning rate was set to $10^{-3}$ (the shallower the model, the appropriately larger the learning rate can be). The main comparison is the improvement brought by adjusting the CRF layer's learning rate. From the table, we can see:

1. With an appropriate learning rate, CRF outperforms Softmax;

2. Appropriately increasing the CRF layer's learning rate also yields improvements over the original CRF.

This shows that for models whose fitting capacity is not exceptionally powerful (such as using only the first few layers of BERT, or for particularly difficult tasks where even full BERT capacity isn't sufficient), CRF and its transition matrix are indeed helpful. Furthermore, fine-tuning the CRF layer's learning rate can bring even greater improvements. All the above experiments were based on BERT, but would a similar approach work for traditional BiLSTM+CRF or CNN+CRF? I did a few simple tests and found it helpful in some cases, so it is likely a general trick for CRF layers.

Summary

Starting from an example added to bert4keras, this post observes that when BERT is combined with CRF, the CRF layer might suffer from insufficient training. I hypothesized a possible reason and further validated the hypothesis through experiments. Finally, I proposed increasing the CRF layer's learning rate as a way to enhance CRF performance and verified its effectiveness (in certain tasks).