Comparison of Gradient and Integrated Gradients in the original paper (CV task; Integrated Gradients highlights key features more finely)

By 苏剑林 | June 28, 2020

This article introduces a neural network visualization method: Integrated Gradients. It was first proposed in the paper "Gradients of Counterfactuals" and subsequently introduced again in "Axiomatic Attribution for Deep Networks". Both papers share the same authors and largely the same content, though the latter is relatively easier to understand; if you plan to read the original research, I recommend the latter. Of course, this work dates back to 2016–2017. Calling it "novel" refers to its innovative and interesting approach, rather than its recentness.

Neural network visualization, simply put, means identifying which components of an input $x$ significantly influence the decision of a model $F(x)$, or ranking the importance of the individual components of $x$—a process professionally known as "attribution." A naive approach is to use the gradient $\nabla_x F(x)$ directly as an indicator of importance for each component of $x$. Integrated Gradients is an improvement upon this idea. However, I believe many articles explaining Integrated Gradients (including the original papers) are too "rigid" or formal, and fail to highlight the fundamental reason why Integrated Gradients is more effective than the naive gradient. I will attempt to introduce the Integrated Gradients method using my own perspective.

First, let's examine gradient-based methods, which are essentially based on Taylor expansion:

\begin{equation} F(x+\Delta x) - F(x) \approx \langle\nabla_x F(x), \Delta x\rangle=\sum_i [\nabla_x F(x)]_i \Delta x_i \label{eq:g} \end{equation}We know that $\nabla_x F(x)$ is a vector of the same size as $x$. Here, $[\nabla_x F(x)]_i$ is its $i$-th component. For a fixed-magnitude change $\Delta x_i$, the larger the absolute value of $[\nabla_x F(x)]_i$, the larger the change in $F(x+\Delta x)$ relative to $F(x)$. In other words:

$[\nabla_x F(x)]_i$ measures the sensitivity of the model to the $i$-th component of the input, so we use $|[\nabla_x F(x)]_i|$ as the importance metric for that component.

This approach is simple and direct, as described in papers like "How to Explain Individual Classification Decisions" and "Deep Inside Convolutional Networks: Visualising Image Classification Models and Saliency Maps." While it successfully explains many results, it has obvious drawbacks. Many articles point out the case of saturation regions; once the input enters a saturation region (typically the negative half of a $\text{relu}$), the gradient becomes zero, revealing no useful information.

From a practical standpoint, this understanding is reasonable, but I believe it is not profound enough. As discussed in a previous article "A Brief Discussion on Adversarial Training", the goal of adversarial training can be understood as pushing $\Vert\nabla_x F(x)\Vert^2 \to 0$. This suggests that gradients can be "manipulated." Even without affecting a model's prediction accuracy, we can make its gradients as close to zero as possible. Thus, returning to the theme of this article: $[\nabla_x F(x)]_i$ indeed measures the sensitivity of the model to the $i$-th component of the input, but sensitivity is not a sufficient measure of importance.

Given the shortcomings of direct gradient usage, several improvements have been proposed, such as LRP and DeepLift. However, I find the improvement offered by Integrated Gradients to be more concise and elegant.

First, we need to view the problem from a different angle: our goal is to find important components, but this importance should not be absolute; it should be relative. For instance, to identify trending words, we shouldn't search based on raw frequency alone; otherwise, we'd only find stop words like "the" or "of." Instead, we should prepare a "reference" frequency table calculated from a balanced corpus and compare the frequency differences rather than the absolute values. This tells us that to measure the importance of components in $x$, we also need a "reference background" $\bar{x}$.

In many scenarios, we can simply set $\bar{x}=0$, though this isn't always optimal. For example, we could choose $\bar{x}$ as the mean of all training samples. We expect $F(\bar{x})$ to yield a "neutral" prediction, such as balanced probabilities for every class in a classification model. We then consider $F(\bar{x}) - F(x)$, which we can imagine as the cost of moving from $x$ to $\bar{x}$.

If we use the approximate expansion in $\eqref{eq:g}$, we get:

\begin{equation} F(\bar{x})-F(x) \approx \sum_i [\nabla_x F(x)]_i [\bar{x} - x]_i \label{eq:g2} \end{equation}Regarding this equation, we can derive a new interpretation:

The total cost of moving from $x$ to $\bar{x}$ is $F(\bar{x}) - F(x)$, which is the sum of the costs of each component. Each component's cost is approximately $[\nabla_x F(x)]_i [\bar{x} - x]_i$. Therefore, we can use $|[\nabla_x F(x)]_i [\bar{x} - x]_i|$ as the importance metric for the $i$-th component.

Of course, mathematically, the flaws of $|[\nabla_x F(x)]_i [\bar{x} - x]_i|$ are the same as those of $[\nabla_x F(x)]_i$ (gradient vanishing), but the corresponding explanation is different. As mentioned earlier, the flaw of $[\nabla_x F(x)]_i$ stems from "sensitivity not being a good measure of importance." Looking at the logic in this section, the flaw of $|[\nabla_x F(x)]_i [\bar{x} - x]_i|$ is simply that "the equality in $\eqref{eq:g2}$ only holds approximately," though the underlying logical reasoning is sound.

Often, a new explanation brings a fresh perspective, which in turn inspires new improvements. Referring back to the previous critique—that $|[\nabla_x F(x)]_i [\bar{x} - x]_i|$ is suboptimal because $\eqref{eq:g2}$ is imprecise—if we could find an exact identity with a similar expression, the problem would be solved. Integrated Gradients provides exactly such an expression. Let $\gamma(\alpha), \alpha \in [0,1]$ represent a parametric curve connecting $x$ and $\bar{x}$, where $\gamma(0)=x$ and $\gamma(1)=\bar{x}$. We then have:

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} F(\bar{x})-F(x) =& F(\gamma(1))-F(\gamma(0))\\ =& \int_0^1 \frac{dF(\gamma(\alpha))}{d\alpha}d\alpha\\ =& \int_0^1 \left\langle\nabla_{\gamma} F(\gamma(\alpha)), \gamma'(\alpha)\right\rangle d\alpha\\ =& \sum_i \int_0^1 \left[\nabla_{\gamma} F(\gamma(\alpha))\right]_i \left[\gamma'(\alpha)\right]_i d\alpha \end{aligned} \label{eq:g3} \end{equation}As we can see, equation $\eqref{eq:g3}$ shares the same form as $\eqref{eq:g2}$, except $[\nabla_x F(x)]_i [\bar{x} - x]_i$ is replaced by $\int_0^1 \left[\nabla_{\gamma} F(\gamma(\alpha))\right]_i \left[\gamma'(\alpha)\right]_i d\alpha$. Since $\eqref{eq:g3}$ is an exact integral identity, Integrated Gradients proposes using:

\begin{equation} \left\|\int_0^1 \left[\nabla_{\gamma} F(\gamma(\alpha))\right]_i \left[\gamma'(\alpha)\right]_i d\alpha\right\| \label{eq:ig-1} \end{equation}as the importance measure for the $i$-th component. Naturally, the simplest path $\gamma(\alpha)$ is a straight line between the two points:

\begin{equation} \gamma(\alpha) = (1 - \alpha) x + \alpha \bar{x} \end{equation}In this case, Integrated Gradients is specifically expressed as:

\begin{equation} \left\|\left[\int_0^1 \nabla_{\gamma} F(\gamma(\alpha))\big\|_{\gamma(\alpha) = (1 - \alpha) x + \alpha \bar{x}}d\alpha\right]_i \left[\bar{x}-x\right]_i\right\| \label{eq:ig-2} \end{equation}Compared to $|[\nabla_x F(x)]_i [\bar{x} - x]_i|$, the gradient $\nabla_x F(x)$ is replaced by the integral of the gradient $\int_0^1 \nabla_{\gamma} F(\gamma(\alpha))\big\|_{\gamma(\alpha) = (1 - \alpha) x + \alpha \bar{x}}d\alpha$, which is the average gradient of every point on the line from $x$ to $\bar{x}$. Intuitively, because gradients along the entire path are considered, the method is no longer limited by a zero gradient at a single point.

Readers of the original Integrated Gradients papers may notice their introduction is inverse: they start by suddenly presenting $\eqref{eq:ig-2}$, then prove it satisfies two specific properties (Sensitivity and Implementation Invariance), and finally prove it satisfies $\eqref{eq:g3}$. In short, they take the reader on a long detour without clearly stating the fundamental reason why it is a better measure of importance: both methods are based on decomposing $F(\bar{x}) - F(x)$, and equation $\eqref{eq:g3}$ is simply more precise than $\eqref{eq:g2}$.

Finally, how do we calculate this integral? Deep learning frameworks don't have built-in integration functions. It's actually simple: based on the "approximation then limit" definition of an integral, we use discrete approximation. Using $\eqref{eq:ig-2}$ as an example, it is approximated as:

\begin{equation} \left\|\left[\frac{1}{n}\sum_{k=1}^n\Big(\nabla_{\gamma} F(\gamma(\alpha))\big\|_{\gamma(\alpha) = (1 - \alpha) x + \alpha \bar{x}, \alpha=k/n}\Big)\right]_i \left[\bar{x}-x\right]_i\right\| \end{equation}So, as previously stated, the essence is "the average of the gradients at every point on the line from $x$ to $\bar{x}$," which works better than a single point's gradient.

Having covered the theory, let's look at the experimental performance.

Original paper implementation: https://github.com/ankurtaly/Integrated-Gradients

Here are some effect comparison images from the original paper:

Comparison of Gradient and Integrated Gradients in the original paper (CV task; Integrated Gradients highlights key features more finely)

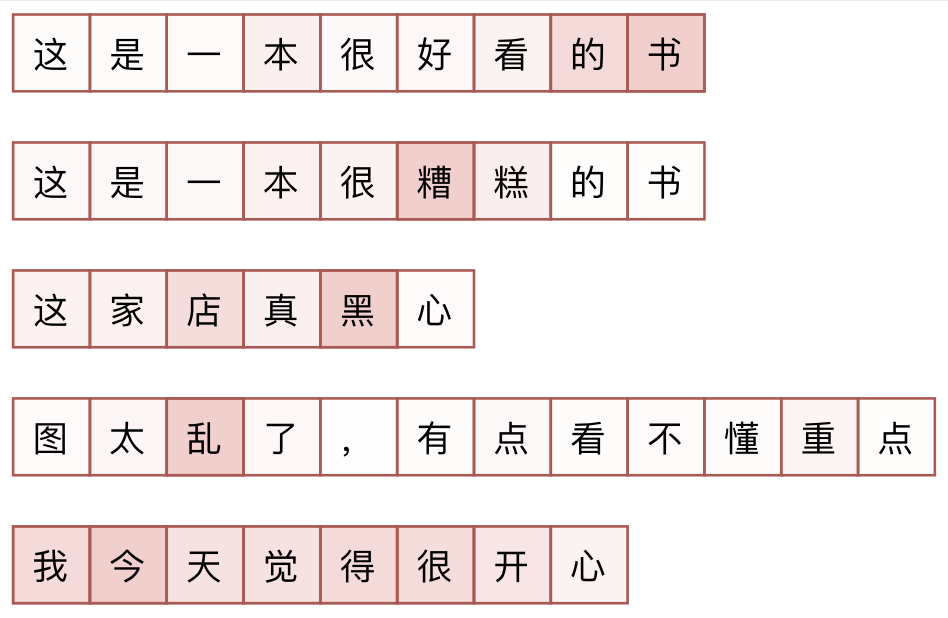

Comparison of Gradient and Integrated Gradients in the original paper (NLP task; red is positive correlation, blue is negative correlation, grey is irrelevant)

Although the Keras official website already provides a reference implementation (see here), the code is quite long and tiring to read. I have implemented a version in Keras based on my own understanding and applied it to NLP. The code can be found at: task_sentiment_integrated_gradients.py. The current code is just a simple demo, and readers are welcome to derive more powerful versions from it.

Integrated Gradients experimental results on Chinese sentiment classification (redder tokens are more important)

In the figure above, I provide results for several samples (the model correctly predicted the sentiment tags for all these samples). From these, we can infer how the original model performs sentiment classification. For negative samples, the Integrated Gradients reasonably locate the negative words in the sentence. For positive samples, however, even if the grammatical structure is the same as the negative samples, the method fails to locate the positive words. This phenomenon suggests that the model might be performing "negative detection"—identifying negative sentiment and classifying anything without negative sentiment as positive. This is likely a result of training without "neutral" samples.

This article introduced a neural network visualization method called "Integrated Gradients," which identifies the importance of input components. By integrating gradients along a path, Integrated Gradients constructs an exact identity that compensates for the shortcomings of Taylor expansion, achieving better visualization results than the direct use of gradients.

If you would like to cite this article, please use: