By 苏剑林 | September 10, 2020

Some time ago, during a technical sharing session at the company, it was the author's turn to present. Everyone hoped I would talk about VAE. Given that I have previously written a Variational Autoencoder series, I thought it wouldn't be particularly difficult, so I agreed. However, on second thought, I found myself in a dilemma: how should I present it?

Regarding VAE, I previously wrote two systematic introductions: "Variational Autoencoder (I): So That's How It Is" and "Variational Autoencoder (II): From a Bayesian Perspective". The latter is pure probabilistic derivation, which might not be meaningful or easily understood by those not doing theoretical research. While the former is simpler, it is also somewhat inadequate because it explains things from the perspective of generative models without clearly explaining "why VAE is needed" (to put it plainly, VAE can result in a generative model, but VAE is not necessarily just for generative models), and the overall style is not particularly friendly.

I thought about it, and for most readers who don't understand VAE but want to use it, they probably only want a rough understanding of the form of VAE and want to know the answers to questions like "What is the role of VAE?", "What is the difference between VAE and AE?", and "In what scenarios is VAE needed?". The above two articles cannot satisfy these needs well. Therefore, I tried to conceive a geometric picture of VAE, attempting to describe the key characteristics of VAE from a geometric perspective, which I would like to share with everyone here.

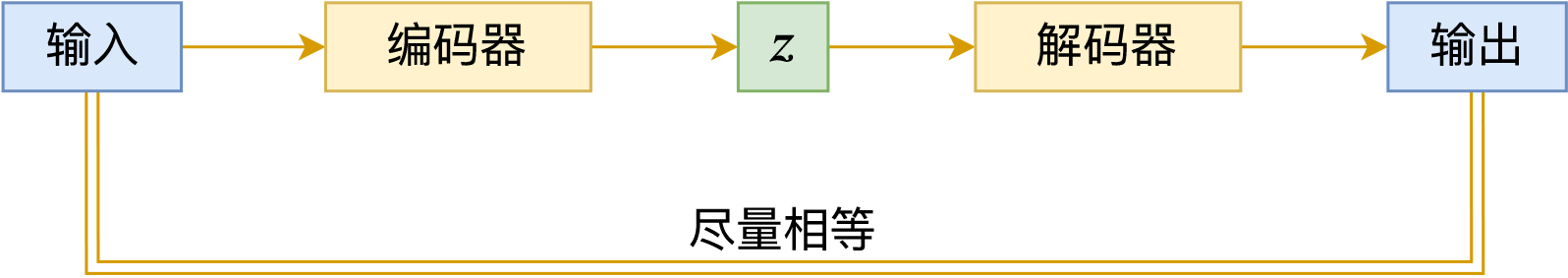

We start with the Autoencoder (AE). The original intention of the autoencoder was for data dimension reduction. Suppose the original feature $x$ has too high a dimension; we hope to encode it into a low-dimensional feature vector $z=E(x)$ through an encoder $E$. The principle of encoding is to retain original information as much as possible, so we train a decoder $D$, hoping to reconstruct the original information through $z$, i.e., $x \approx D(E(x))$. The optimization objective is generally:

\[E,D = \text{argmin}_{E,D} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim \mathcal{D}} [\|x - D(E(x))\|^2]\]The corresponding schematic diagram is as follows:

Autoencoder Schematic

If every sample can be reconstructed well, then we can consider $z$ as an equivalent representation of $x$. In other words, studying $z$ well is equivalent to studying $x$ well. Now we encode each $x$ into a corresponding feature vector $z$, and then we are concerned with a question: what does the space covered by these $z$ "look like"?

After an autoencoder, each original sample corresponds to a point in the coding space.

Why care about this question? Because we can have many different encoding methods, and the feature vectors obtained by different encoding methods vary in quality. From "what the coding space looks like," we can roughly see the quality of the feature vectors. For example, below are four simulation diagrams of the distribution shapes of different encoding vectors:

Four simulation diagrams of different coding space shapes, representing irregular, linear, ring-like, and circular distributions respectively.

The vector distribution in the first image has no special shape and is quite scattered, indicating that the coding space is not particularly regular. The vectors in the second image are concentrated on a line, indicating redundancy between the dimensions of the encoding vectors. The third image is a ring, indicating that there are no corresponding real samples near the center of the circle. The fourth image is a circle, indicating that it regularly covers a continuous space. Looking at the four images, we believe the vector distribution shape depicted in the last image is the most ideal: regular, non-redundant, and continuous. This means that if we learn a portion of the samples from it, it is easy to generalize to unknown new samples, because we know the coding space is regular and continuous. Therefore, we know that the "gaps" between the encoding vectors of training samples (the blank parts between two points in the figure) actually also correspond to unknown real samples. Thus, by handling the known ones well, it is likely that the unknown ones are also handled well.

In general, we are concerned about the following questions regarding the coding space:

1. What kind of region do all encoding vectors cover?

2. Are there unknown real samples corresponding to the vectors in the blank spaces?

3. Are there any vectors that have "lost touch with the crowd"?

4. Is there a way to make the coding space more regular?

A conventional autoencoder has no special constraints, so it is difficult to answer the above questions. Thus, the Variational Autoencoder (VAE) emerged. From an encoding perspective, its purpose is to: 1. Make the coding space more regular; 2. Make the encoding vectors more compact. To achieve this goal, the Variational Autoencoder first introduces a posterior distribution $p(z|x)$.

For readers who do not want to delve into probabilistic language, how should they understand the posterior distribution $p(z|x)$? Intuitively, we can understand the posterior distribution as an "ellipse." Originally, each sample corresponded to an encoding vector, which is a point in the coding space; after introducing the posterior distribution, it is equivalent to saying that now each sample $x$ corresponds to an "ellipse." We just mentioned that we hope the encoding vectors are more "compact," but theoretically speaking, no matter how many "points" there are, they cannot cover a "surface." However, if we use "surfaces" to cover a "surface," it is easy to cover the target. This is one of the main changes made by the Variational Autoencoder.

The coding of each sample changes from a point to an area (ellipse), so the coding space originally covered by points becomes covered by areas.

Readers might ask, why must it be an ellipse? Can it be a rectangle or other shapes? Returning to probabilistic language, an ellipse corresponds to the "assumption that the components of $p(z|x)$ are independent Gaussian distributions." From a probabilistic point of view, the Gaussian distribution is a relatively easy class of probability distributions to handle, so we use the Gaussian distribution, which corresponds to an ellipse. Other shapes would correspond to other distributions; for example, a rectangle could correspond to a uniform distribution, but it would be more troublesome when calculating KL divergence later, so it is generally not used.

Now each sample $x$ corresponds to an "ellipse," and determining an "ellipse" requires two pieces of information: the center of the ellipse and the axial lengths. They each constitute a vector, and these vectors depend on the sample $x$, which we denote as $\mu(x), \sigma(x)$. Since the entire ellipse corresponds to sample $x$, we require that any point within the ellipse can reconstruct $x$, so the training target is:

\[\mu,\sigma,D = \text{argmin}_{\mu,\sigma,D} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim \mathcal{D}} [\|x - D(\mu(x) + \epsilon \otimes \sigma(x))\|^2], \quad \epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0, I)\]Where $\mathcal{D}$ is the training data, and $\mathcal{N}(0, I)$ is the standard normal distribution. We can understand it as a unit circle. In other words, we first sample $\epsilon$ from the unit circle, and then transform it into a point inside an ellipse with "center $\mu(x)$ and axial length $\sigma(x)$" through the translation and scaling transformation $\mu(x) + \epsilon \otimes \sigma(x)$. This process is the so-called "Reparameterization."

Here, $\mu(x)$ actually corresponds to the encoder $E(x)$ in the autoencoder, and $\sigma(x)$ corresponds to the range it can generalize to.

Finally, while the "ellipse" can "make the encoding vectors more compact," it cannot yet "make the coding space more regular." Now we want the encoding vectors to satisfy the standard normal distribution (which can be understood as a unit circle), i.e., the space covered by all ellipses together forms a unit circle.

To this end, we hope that each ellipse can move closer to the unit circle. The center of the unit circle is 0 and the radius is 1, so a basic idea is to introduce a regularization term:

\[\mathbb{E}_{x \sim \mathcal{D}} [\|\mu(x) - 0\|^2 + \|\sigma(x) - 1\|^2]\]In fact, combining these two loss terms already makes it very close to the standard Variational Autoencoder. The standard Variational Autoencoder uses a slightly more complex regularization term with similar functionality:

\[\mathbb{E}_{x \sim \mathcal{D}} \left[ \sum_{i=1}^d \frac{1}{2}(\mu_i^2(x) + \sigma_i^2(x) - \log \sigma_i^2(x) - 1) \right]\]This regularization term originates from the KL divergence between two Gaussian distributions, so it is also commonly called the "KL divergence term."

Variational Autoencoder Schematic

Combining the two targets yields the final Variational Autoencoder:

\[\|x - D(\mu(x) + \epsilon \otimes \sigma(x))\|^2 + \sum_{i=1}^d \frac{1}{2}(\mu_i^2(x) + \sigma_i^2(x) - \log \sigma_i^2(x) - 1), \quad \epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0, I)\]This article introduced an understanding of the Variational Autoencoder (VAE) from the perspective of geometric analogy. From this viewpoint, the goal of the Variational Autoencoder is to make the encoding vectors more compact and regulate the encoding distribution to be a standard normal distribution (unit circle).

In this way, VAE can achieve two effects: 1. By randomly sampling a vector from the standard Gaussian distribution (unit circle), one can obtain a real sample through the decoder, thus realizing a generative model; 2. Due to the compactness of the coding space and the noise added to the encoding vectors during training, the components of the encoding vector can achieve a certain degree of decoupling and be endowed with certain linear operation properties.

The geometric perspective allows us to quickly grasp the key characteristics of the Variational Autoencoder and reduces the difficulty of entry, but it also has certain inaccuracies. If there are any inappropriate parts, I hope readers can understand and point them out.