Teacher Forcing Schematic

By 苏剑林 | October 27, 2020

Teacher Forcing is the classic training method for Seq2Seq models, and Exposure Bias is the classic deficiency of Teacher Forcing. This is a well-known fact for students working on text generation. I have previously written a blog post "A Brief Analysis and Countermeasures for the Exposure Bias Phenomenon in Seq2Seq", which initially analyzed the Exposure Bias problem.

This article introduces a scheme proposed by Google called "TeaForN" to alleviate the Exposure Bias phenomenon, from the paper "TeaForN: Teacher-Forcing with N-grams". Through a nested iterative approach, it allows the model to predict the next $N$ tokens in advance (rather than just the current token to be predicted). The logic behind its approach is quite remarkable and worth learning.

(Note: To maintain consistency with previous articles on this blog, the notation in this article differs from that in the original paper. Please focus on understanding the meaning of the symbols rather than memorizing their specific forms.)

The article "A Brief Analysis and Countermeasures for the Exposure Bias Phenomenon in Seq2Seq" has already introduced Teacher Forcing in detail; here is just a brief review. First, the Seq2Seq model decomposes the joint probability into the product of multiple conditional probabilities, which is the so-called "autoregressive model":

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}p(\boldsymbol{y}|\boldsymbol{x})=&\,p(y_1,y_2,\dots,y_n|\boldsymbol{x})\\ =&\,p(y_1|\boldsymbol{x})p(y_2|\boldsymbol{x},y_1)\dots p(y_n|\boldsymbol{x},y_1,\dots,y_{n-1}) \end{aligned}\end{equation}Then, when we train the model for step $t$, $p(y_t|\boldsymbol{x},y_1,\dots,y_{t-1})$, we assume that $\boldsymbol{x}, y_1, \dots, y_{t-1}$ are all known and let the model predict only $y_t$. This is Teacher Forcing. However, during the inference phase, the true $y_1, \dots, y_{t-1}$ are unknown; they are predicted recursively, which may lead to issues like error propagation. Therefore, the problem with Teacher Forcing is the inconsistency between training and inference, which makes it difficult to gauge the inference performance from the training process.

How can we more specifically understand the problem caused by this inconsistency? We can think of it as "lacking farsightedness." In the decoder, the input $\boldsymbol{x}$ and the previous $t-1$ output tokens are encoded together to obtain the vector $h_t$. In Teacher Forcing, this $h_t$ is only used to predict $y_t$ and has no direct connection with $\boldsymbol{y}_{> t}$. In other words, its "vision" is limited to step $t$.

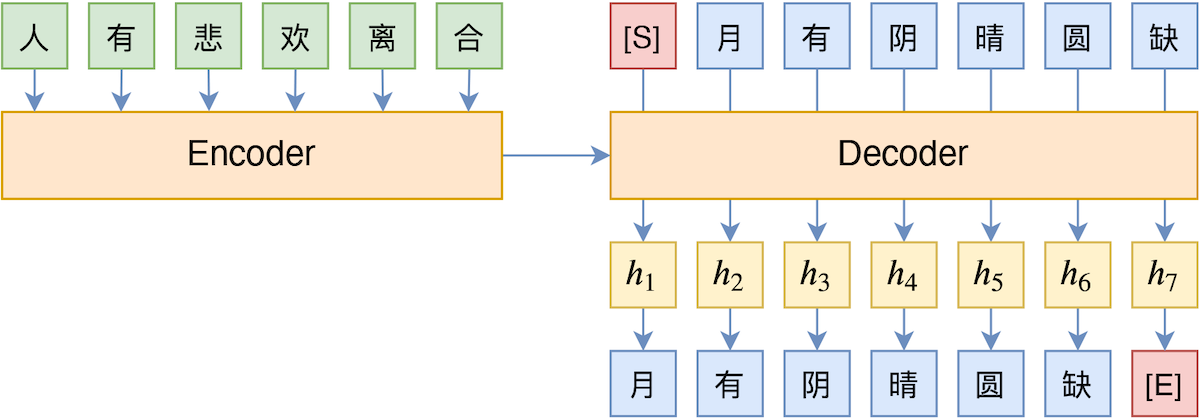

Teacher Forcing Schematic

For example, in the diagram above, the $h_3$ vector: Teacher Forcing only uses it to predict "Yin" (阴). In reality, the prediction result of "Yin" will also affect the prediction of "Qing" (晴), "Yuan" (圆), and "Que" (缺). That is to say, $h_3$ should also be associated with "Qing", "Yuan", and "Que", but Teacher Forcing does not explicitly establish this association. Consequently, when decoding, the model is likely to output tokens with the highest local probability at each step, which easily leads to high-frequency "safe" responses or repetitive decoding phenomena.

To improve the "foresight" of the model, the most thorough way is, of course, to conduct training in the same way as decoding—that is, $h_1, h_2, \dots, h_t$ are predicted recursively just like in the decoding phase, without relying on ground truth labels. We might call this method Student Forcing. However, the Student Forcing training method brings two serious problems:

First, sacrifice of parallelism. For Teacher Forcing, if the Decoder uses a structure like a CNN or Transformer, all tokens can be trained in parallel during the training phase (though inference is still serial). But with Student Forcing, it is always serial.

Second, extreme difficulty in convergence. Student Forcing usually requires Gumbel Softmax or Reinforcement Learning to backpropagate gradients, both of which face severe training instability. Generally, Teacher Forcing pre-training is required before using Student Forcing, but even then, it is not particularly stable.

Metaphorically, Student Forcing is like a teacher letting a student independently explore a complex problem without any step-by-step guidance, providing only a final evaluation of the result. If the student can successfully explore it, it shows the student's ability is very strong, but the problem is the lack of the teacher's "patient guidance," making the chance of the student "hitting a wall" much higher.

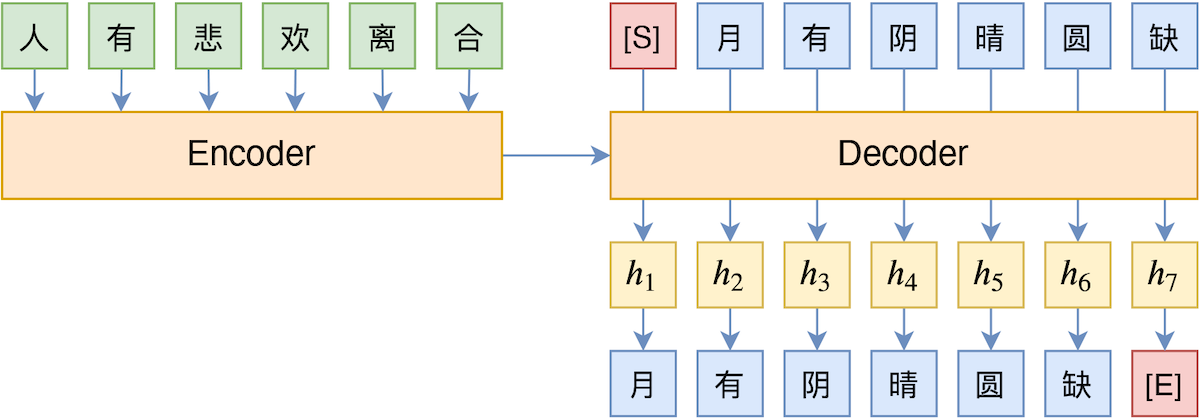

Is there a method between Teacher Forcing and Student Forcing? Yes, the TeaForN introduced in this article is one such method. Its idea is that while conventional Teacher Forcing corresponds to looking 1 step ahead during training, and Student Forcing corresponds to looking $L$ steps ahead (where $L$ is the target sentence length), if we look just a few steps ahead (equivalent to seeing N-grams), we can theoretically improve "foresight" without severely sacrificing the model's parallelism. Its schematic is as follows:

TeaForN Schematic

Intuitively, the output results are iterated forward multiple times. In this way, what the first $t-1$ tokens need to predict is not just the $t$-th token, but also the $(t+1)$-th, $(t+2)$-th, and so on. For example, in the diagram above, we finally use $h_6^{(3)}$ to predict the word "Que." As we can see, $h_6^{(3)}$ depends only on the three words "Yue" (月 - moon), "You" (有 - has), and "Yin" (阴 - shadow). Thus, we can also understand it as the vector $h_4^{(1)}$ having to predict the three words "Qing", "Yuan", and "Que" simultaneously, thereby increasing its "foresight."

To describe it in mathematical language, we can divide the Decoder into two parts: an embedding layer $E$ and the remaining part $M$. The embedding layer is responsible for mapping the input sentence $s=[w_0, w_1, w_2, \dots, w_{L-1}]$ to a sequence of vectors $[e_0, e_1, e_2, \dots, e_{L-1}]$ (where $w_0$ is a fixed start-of-decoding token, which is the [S] in the diagram above, recorded as <bos> in some articles). This is then handed to model $M$ for processing to obtain a sequence of vectors $[h_1, h_2, h_3, \dots, h_L]$, i.e.,

\begin{equation}[h_1, h_2, h_3, \dots, h_L] = M(E([w_0, w_1, w_2, \dots, w_{L-1}]))\end{equation}Next, the token probability distribution at step $t$ is obtained via $p_t = \text{softmax}(Wh_t + b)$. Finally, $-\log p_t[w_t]$ is used as the loss function for training. This is conventional Teacher Forcing.

One can imagine that the output vector sequence $[h_1, h_2, h_3, \dots, h_{L-1}]$, which is responsible for mapping to the token distribution, is in some sense similar to the embedding sequence $[e_1, e_2, e_3, \dots, e_{L-1}]$. If we supplement an $e_0$ and then feed $[e_0, h_1, h_2, \dots, h_{L-1}]$ back into model $M$ for processing once more, would that work? That is:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned} [e_0, e_1, e_2, \dots, e_{L-1}] &= E([w_0, w_1, w_2, \dots, w_{L-1}]) \\ [h_1^{(1)}, h_2^{(1)}, h_3^{(1)}, \dots, h_L^{(1)}] &= M([e_0, e_1, e_2, \dots, e_{L-1}]) \\ [h_1^{(2)}, h_2^{(2)}, h_3^{(2)}, \dots, h_L^{(2)}] &= M([e_0, h_1^{(1)}, h_2^{(1)}, \dots, h_{L-1}^{(1)}]) \\ [h_1^{(3)}, h_2^{(3)}, h_3^{(3)}, \dots, h_L^{(3)}] &= M([e_0, h_1^{(2)}, h_2^{(2)}, \dots, h_{L-1}^{(2)}]) \\ &\vdots \end{aligned}\end{equation}Then for every $h$, we calculate the probability distribution $p_t^{(i)} = \text{softmax}(Wh_t^{(i)} + b)$. Finally, the cross-entropy is calculated and weighted linearly:

\begin{equation}\text{loss} = -\sum_{t=1}^L \sum_{i=1}^N \lambda_i \log p_t^{(i)}[w_t]\end{equation}After training is complete, we only use $E$ and $M$ for conventional decoding operations (such as Beam Search), which means only $h_t^{(1)}$ is used, and $h_t^{(2)}, h_t^{(3)}, \dots$ are no longer needed. This process is the protagonist of this article: TeaForN.

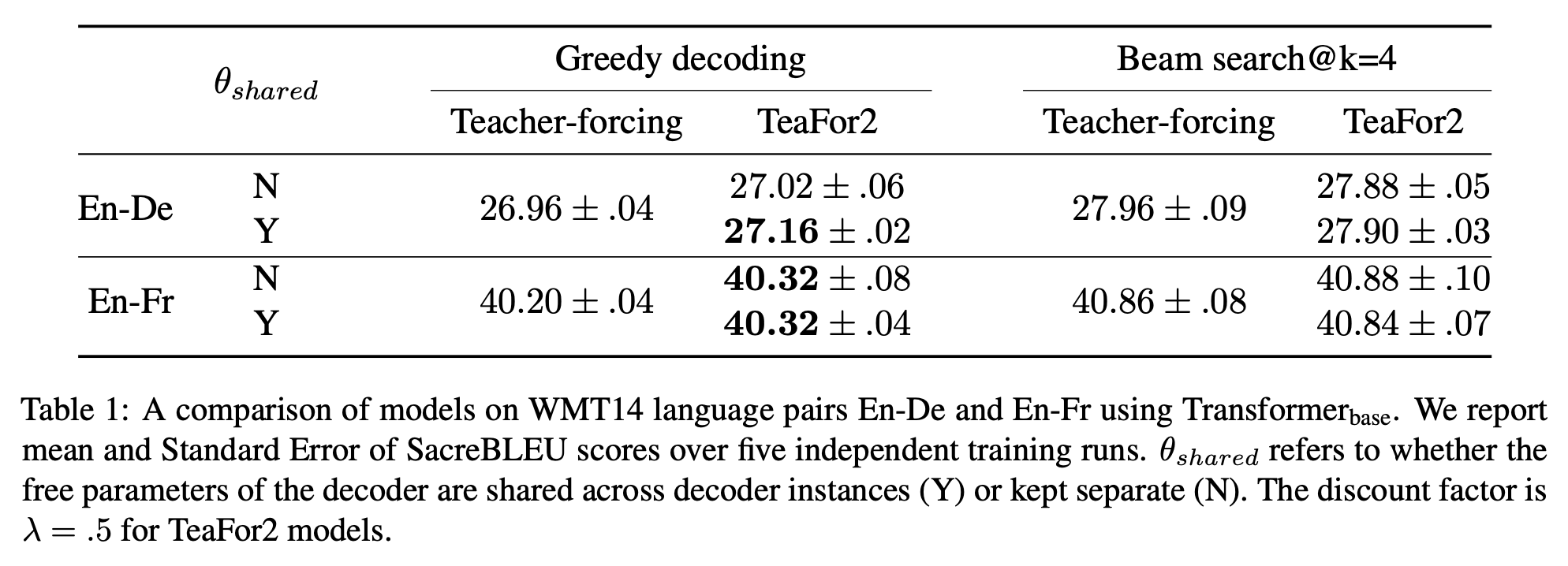

As for the experimental results, there is naturally an improvement. From the experimental tables in the original paper, the improvement is more significant when beam_size is relatively large. This is not hard to understand; theoretically, this processing should at least not lead to a performance drop, so it can be considered a "win-win" strategy.

TeaForN Experimental Results (Text Summarization)

The original paper discusses a few points worth debating; let's look at them here.

First, should the $M$ used in each step of the iteration share weights? Intuitively, sharing is better. If weights are not shared, looking forward $N$ steps would make the parameter count roughly $N$ times the original, which doesn't seem good. Of course, it's best to rely on experiments. The original paper did perform this comparison and confirmed our intuition.

TeaForN on Machine Translation, including weight-sharing comparison

Second, perhaps the main question is: Is it really reliable to use $[h_1, h_2, h_3, \dots, h_{L-1}]$ as $[e_1, e_2, e_3, \dots, e_{L-1}]$ during the iteration process? Of course, experimental results have already shown it's feasible, which is the most convincing argument. However, since $h_t$ is mapped to $p_t$ through an inner product, $h_t$ is not necessarily similar to $e_t$. If we could make them closer, would the effect be better? The original paper considered the following approach:

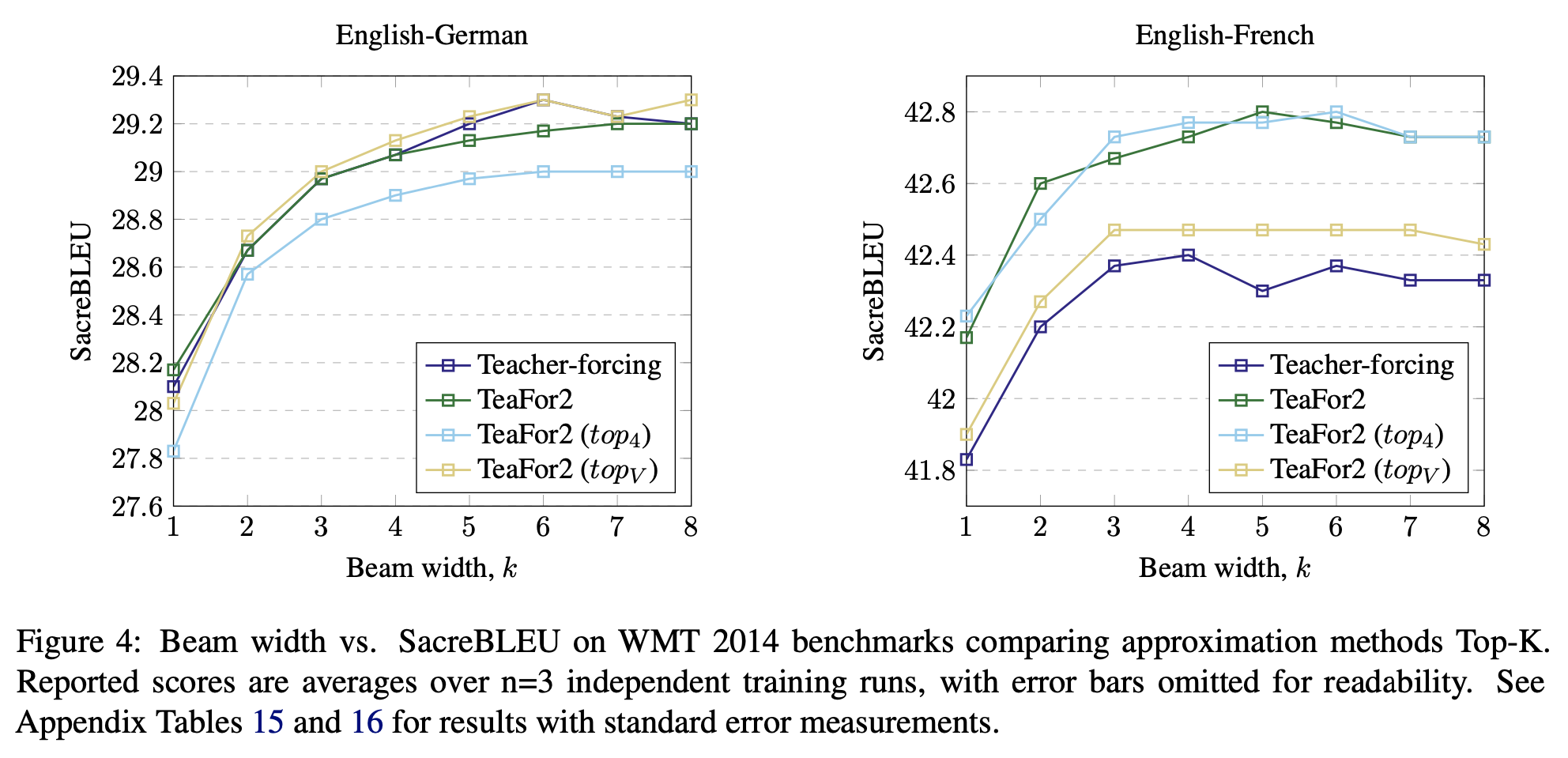

\begin{equation}\frac{\sum_{w\in \text{Top}_k(p_t)} p_t[w] e_w}{\sum_{w\in \text{Top}_k(p_t)} p_t[w]}\end{equation}In other words, after calculating $p_t$ at each step, take the $k$ tokens with the highest probability and use the weighted average of their embedding vectors as the input for the next iteration. The original paper experimented with $k=4$ and $k=|V|$ (vocabulary size); the results are shown below. Overall, the performance with Top-k was not particularly stable, and even in good cases, it was similar to directly using $h_t$. Therefore, there's no need to try anything else.

Effect of substituting h with weighted average embeddings using Top-k

Of course, I think it would have been even more perfect if the paper had also compared the effect of simulating sampling via Gumbel Softmax.

In this article, we shared a new training method called TeaForN proposed by Google. It sits between Teacher Forcing and Student Forcing, mitigating the Exposure Bias problem of the model without severely sacrificing the parallelism of model training. It is a strategy worth trying. Beyond that, it actually provides a new way of thinking about such problems (maintaining parallelism and foresight through iteration), which is quite worthy of reflection.