By 苏剑林 | March 08, 2021

Recently, the author has made some attempts to understand and improve the Transformer, gaining some experiences and conclusions that seem valuable. Consequently, I am starting a special series to summarize these findings, named "Transformer Upgrade Road," representing both a deepening of understanding and improvements in results.

As the first article in this series, I will introduce a new understanding of the Sinusoidal position encoding proposed by Google in "Attention is All You Need":

\begin{equation}\left\{\begin{aligned}&\boldsymbol{p}_{k,2i}=\sin\Big(k/10000^{2i/d}\Big)\\

&\boldsymbol{p}_{k, 2i+1}=\cos\Big(k/10000^{2i/d}\Big)

\end{aligned}\right.\label{eq:sin}\end{equation}

where $\boldsymbol{p}_{k,2i}, \boldsymbol{p}_{k,2i+1}$ are the $2i$-th and $(2i+1)$-th components of the encoding vector for position $k$, and $d$ is the vector dimension.

As an explicit solution for position encoding, Google's description of it in the original paper was sparse, merely mentioning that it could express relative position information. Later, various interpretations appeared on platforms like Zhihu, and some of its characteristics gradually became known, but they remain generally scattered. In particular, fundamental questions such as "How was it conceived?" and "Is this specific form necessary?" have not yet received satisfactory answers.

Therefore, this article focuses on reflecting upon these questions. During the thinking process, readers might feel as I did: the more one contemplates this design, the more exquisite and beautiful it seems, making one truly marvel at its ingenuity.

Taylor Expansion

Suppose our model is $f(\dots,\boldsymbol{x}_m,\dots,\boldsymbol{x}_n,\dots)$, where the marked $\boldsymbol{x}_m, \boldsymbol{x}_n$ represent the $m$-th and $n$-th inputs respectively. Without loss of generality, let $f$ be a scalar function. For a pure Attention model without an Attention Mask, it is fully symmetric, meaning for any $m, n$:

\begin{equation}f(\dots,\boldsymbol{x}_m,\dots,\boldsymbol{x}_n,\dots)=f(\dots,\boldsymbol{x}_n,\dots,\boldsymbol{x}_m,\dots)\end{equation}

This is why we say Transformers cannot identify positions—the full symmetry. Simply put, the function naturally satisfies the identity $f(x,y)=f(y,x)$, making it impossible to distinguish from the output whether the input was $[x,y]$ or $[y,x]$.

Therefore, what we need to do is break this symmetry, for example, by adding a different encoding vector at each position:

\begin{equation}\tilde{f}(\dots,\boldsymbol{x}_m,\dots,\boldsymbol{x}_n,\dots)=f(\dots,\boldsymbol{x}_m + \boldsymbol{p}_m,\dots,\boldsymbol{x}_n + \boldsymbol{p}_n,\dots)\end{equation}

Generally, as long as the encoding vectors for each position are different, this full symmetry is broken, and $\tilde{f}$ can be used instead of $f$ to process ordered inputs. But now we hope to further analyze the properties of position encoding, or even derive an explicit solution, so we cannot stop here.

To simplify the problem, let's first consider only the position encodings at positions $m$ and $n$. Treating them as perturbation terms, we perform a Taylor expansion to the second order:

\begin{equation}\tilde{f}\approx f + \boldsymbol{p}_m^{\top} \frac{\partial f}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}_m} + \boldsymbol{p}_n^{\top} \frac{\partial f}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}_n} + \frac{1}{2}\boldsymbol{p}_m^{\top} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}_m^2}\boldsymbol{p}_m + \frac{1}{2}\boldsymbol{p}_n^{\top} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}_n^2}\boldsymbol{p}_n + \underbrace{\boldsymbol{p}_m^{\top} \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}_m \partial \boldsymbol{x}_n}\boldsymbol{p}_n}_{\boldsymbol{p}_m^{\top} \boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}} \boldsymbol{p}_n}\end{equation}

As we can see, the 1st term is independent of position. The 2nd to 5th terms depend only on a single position, so they are pure absolute position information. The 6th term is the first interaction term containing both $\boldsymbol{p}_m$ and $\boldsymbol{p}_n$. We denote it as $\boldsymbol{p}_m^{\top} \boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}} \boldsymbol{p}_n$ and hope it can express a certain degree of relative position information.

(This Taylor expansion part refers to the response by 纳米酱 on the Zhihu question "Why does BERT use learned position embedding rather than sinusoidal position encoding?")

Relative Position

Let's start with a simple case, assuming $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}=\boldsymbol{I}$ is the identity matrix. In this case, $\boldsymbol{p}_m^{\top} \boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}} \boldsymbol{p}_n = \boldsymbol{p}_m^{\top} \boldsymbol{p}_n = \langle\boldsymbol{p}_m, \boldsymbol{p}_n\rangle$ is the inner product of the two position encodings. We hope that in this simple example, this term expresses relative position information, meaning there exists some function $g$ such that:

\begin{equation}\langle\boldsymbol{p}_m, \boldsymbol{p}_n\rangle = g(m-n)\label{eq:r1}\end{equation}

Here $\boldsymbol{p}_m, \boldsymbol{p}_n$ are $d$-dimensional vectors. Let's start with the simplest case where $d=2$.

For 2D vectors, we use complex numbers for the derivation, treating the vector $[x,y]$ as a complex number $x + y\text{i}$. According to the rules of complex multiplication, it is not difficult to obtain:

\begin{equation}\langle\boldsymbol{p}_m, \boldsymbol{p}_n\rangle = \text{Re}[\boldsymbol{p}_m \boldsymbol{p}_n^*]\end{equation}

where $\boldsymbol{p}_n^*$ is the complex conjugate of $\boldsymbol{p}_n$, and $\text{Re}[]$ represents the real part of the complex number. To satisfy equation $\eqref{eq:r1}$, we can assume there exists a complex number $\boldsymbol{q}_{m-n}$ such that:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{p}_m \boldsymbol{p}_n^* = \boldsymbol{q}_{m-n}\end{equation}

Taking the real part of both sides gives equation $\eqref{eq:r1}$. To solve this equation, we can use the exponential form of complex numbers, setting $\boldsymbol{p}_m=r_m e^{\text{i}\phi_m}, \boldsymbol{p}_n^*=r_n e^{-\text{i}\phi_n}, \boldsymbol{q}_{m-n}=R_{m-n} e^{\text{i}\Phi_{m-n}}$, which yields:

\begin{equation}r_m r_n e^{\text{i}(\phi_m - \phi_n)} = R_{m-n} e^{\text{i}\Phi_{m-n}}\quad\Rightarrow\quad \left\{\begin{aligned}&r_m r_n = R_{m-n}\\ & \phi_m - \phi_n=\Phi_{m-n}\end{aligned}\right.\end{equation}

For the first equation, substituting $n=m$ gives $r_m^2=R_0$, meaning $r_m$ is a constant; for simplicity, let's set it to 1. For the second equation, substituting $n=0$ gives $\phi_m - \phi_0=\Phi_m$. Setting $\phi_0=0$ for simplicity, we get $\phi_m=\Phi_m$, implying $\phi_m - \phi_n = \phi_{m-n}$. Substituting $n=m-1$ gives $\phi_m - \phi_{m-1}=\phi_1$, which means $\{\phi_m\}$ is just an arithmetic progression with the general term $m\theta$. Therefore, the solution for position encoding in 2D is:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{p}_m = e^{\text{i}m\theta}\quad\Leftrightarrow\quad \boldsymbol{p}_m=\begin{pmatrix}\cos m\theta \\ \sin m\theta\end{pmatrix}\end{equation}

Since the inner product satisfies linear additivity, for higher even dimensions, we can represent the position encoding as a combination of multiple 2D position encodings:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{p}_m = \begin{pmatrix}e^{\text{i}m\theta_0} \\ e^{\text{i}m\theta_1} \\ \vdots \\ e^{\text{i}m\theta_{d/2-1}}\end{pmatrix}\quad\Leftrightarrow\quad \boldsymbol{p}_m=\begin{pmatrix}\cos m\theta_0 \\ \sin m\theta_0 \\ \cos m\theta_1 \\ \sin m\theta_1 \\ \vdots \\ \cos m\theta_{d/2-1} \\ \sin m\theta_{d/2-1} \end{pmatrix}\label{eq:r2}\end{equation}

This also satisfies equation $\eqref{eq:r1}$. Of course, this is just one solution to equation $\eqref{eq:r1}$, not the only one; for our purposes, finding a simple solution is sufficient.

Long-range Decay

Based on the previous assumptions, we derived the form of the position encoding in $\eqref{eq:r2}$, which is essentially the same as the standard Sinusoidal position encoding in $\eqref{eq:sin}$, only with different placement of $\sin$ and $\cos$. Since neurons in a neural network are generally unordered, even shuffling the dimensions results in a valid position encoding. Thus, apart from the specific values for $\theta_i$, there is no fundamental difference between equation $\eqref{eq:r2}$ and equation $\eqref{eq:sin}$.

The choice in equation $\eqref{eq:sin}$ is $\theta_i = 10000^{-2i/d}$. What is the significance of this choice? In fact, this form has a favorable property: it ensures that as $|m-n|$ increases, $\langle\boldsymbol{p}_m, \boldsymbol{p}_n\rangle$ tends toward zero. According to our intuition, inputs with larger relative distance should have weaker correlation, so this property matches our intuition. However, how do periodic trigonometric functions exhibit a decaying trend?

This is indeed a magical phenomenon, originating from the asymptotic zero-convergence of high-frequency oscillatory integrals. Specifically, we can write the inner product as:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}

\langle\boldsymbol{p}_m, \boldsymbol{p}_n\rangle =&\, \text{Re}\left[e^{\text{i}(m-n)\theta_0} + e^{\text{i}(m-n)\theta_1} + \cdots + e^{\text{i}(m-n)\theta_{d/2-1}}\right]\\

=&\,\frac{d}{2}\cdot\text{Re}\left[\sum_{i=0}^{d/2-1} e^{\text{i}(m-n)10000^{-i/(d/2)}}\frac{1}{d/2}\right]\\

\sim&\, \frac{d}{2}\cdot\text{Re}\left[\int_0^1 e^{\text{i}(m-n)\cdot 10000^{-t}}dt\right]

\end{aligned}\end{equation}

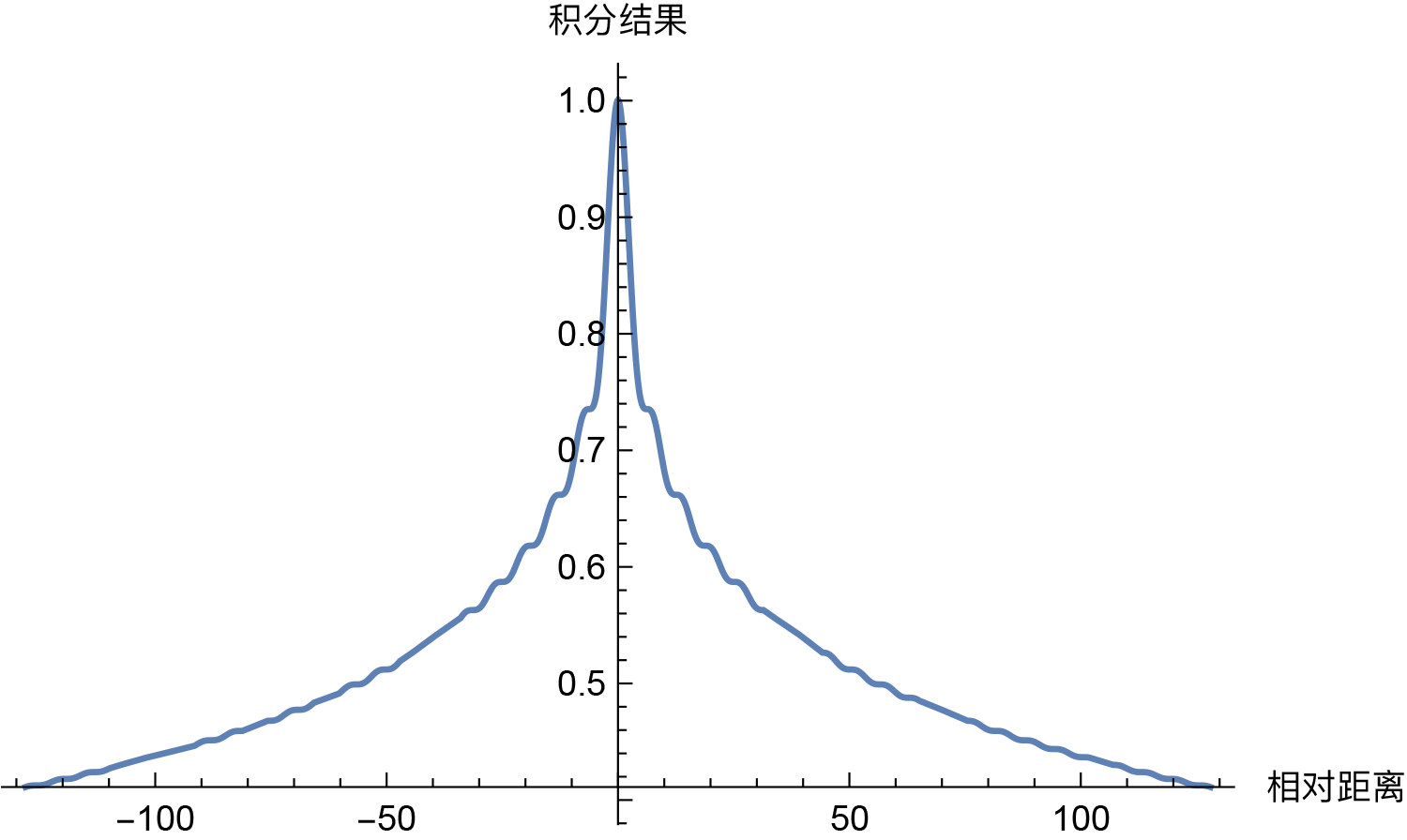

Thus, the problem becomes an asymptotic estimation of the integral $\int_0^1 e^{\text{i}(m-n)\theta_t}dt$. Estimations of such oscillatory integrals are common in quantum mechanics and can be analyzed using those methods. For us, the most direct way is to plot the integral result using Mathematica:

\[Theta][t_] = (1/10000)^t; f[x_] = Re[Integrate[Exp[I*x*\[Theta][t]], {t, 0, 1}]]; Plot[f[x], {x, -128, 128}]

From the image, we can clearly see the decaying trend:

Estimating the decay trend of the Sinusoidal position encoding inner product through direct integration

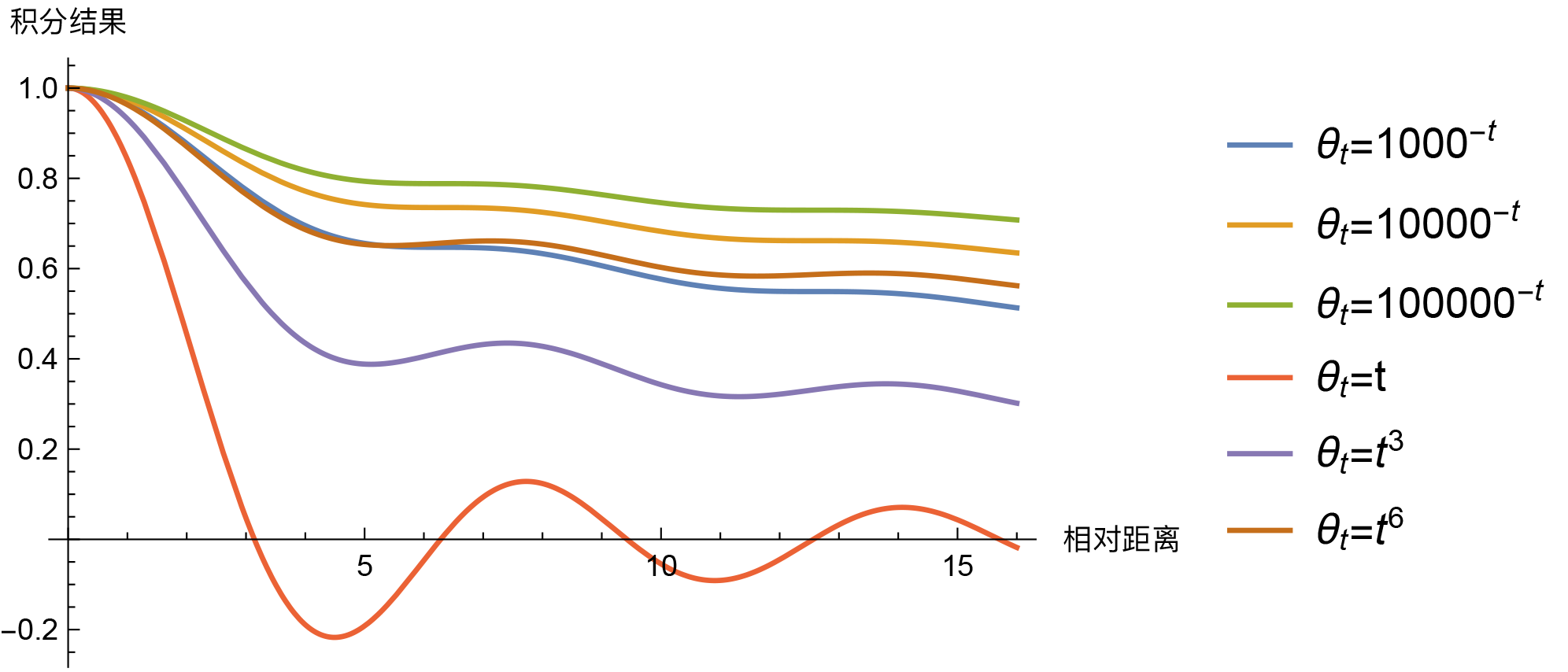

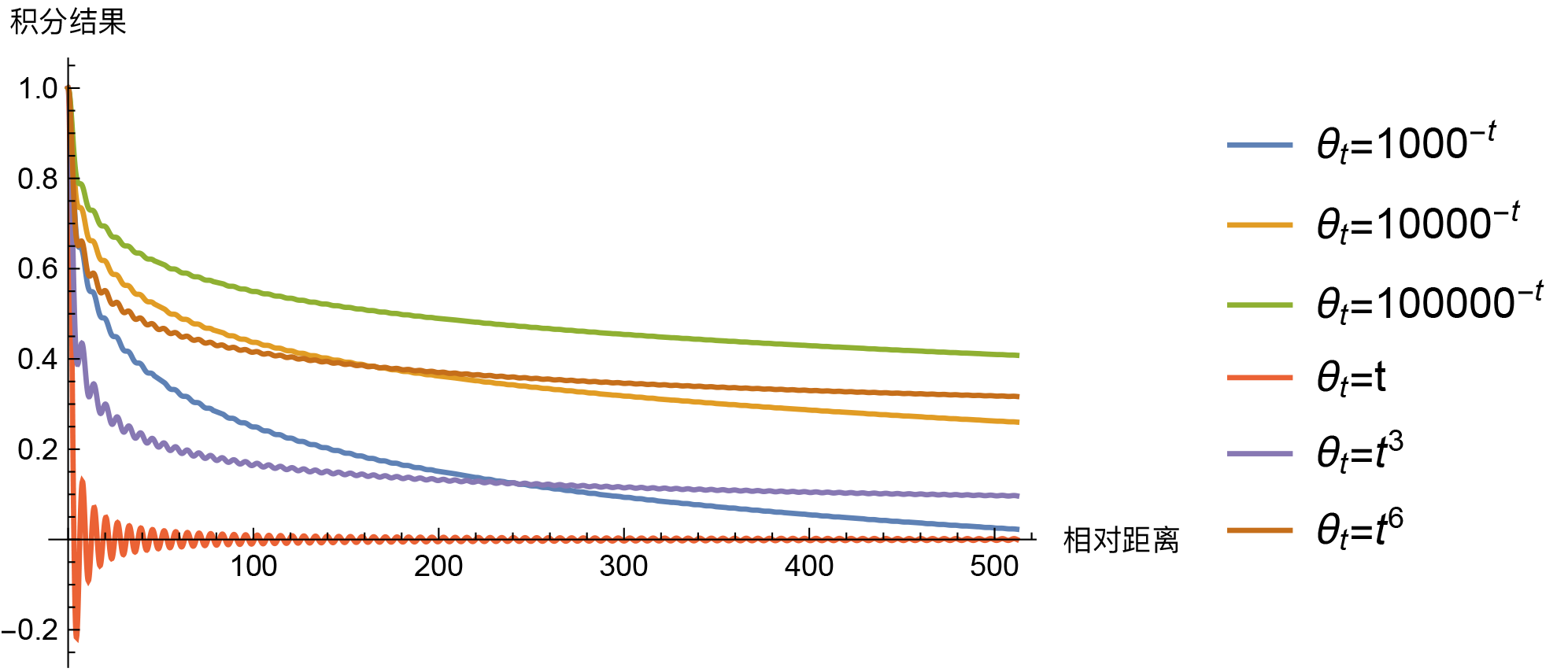

So, the question is, must it be $\theta_t = 10000^{-t}$ to exhibit long-range decay? Of course not. In fact, for our scenario, "almost" any monotonic smooth function $\theta_t$ on $[0,1]$ will make the integral $\int_0^1 e^{\text{i}(m-n)\theta_t}dt$ have an asymptotic decay trend, such as power functions $\theta_t = t^{\alpha}$. Then, what is special about $\theta_t = 10000^{-t}$? Let's compare some results.

Integral results for several different θt (short-distance trend)

Integral results for several different θt (long-distance trend)

Looking at these, except for $\theta_t=t$ which is slightly unusual (intersecting with the horizontal axis), the others don't show much differentiation. It's hard to determine which is better or worse; some drop faster at short distances while others drop faster at long distances. If $\theta_t$ as a whole is closer to 0, the overall drop is slower, and so on. In this light, $\theta_t = 10000^{-t}$ is just a compromise choice without much exclusivity. If I were to choose, I would likely pick $\theta_t = 1000^{-t}$. Another option is to use $\theta_i = 10000^{-2i/d}$ simply as initial values and set them as trainable, letting the model automatically complete the fine-tuning so we don't have to agonize over the choice.

General Case

In the previous two sections, we demonstrated the idea of using absolute position encoding to express relative position information. Combined with the constraint of long-range decay, we can "reverse-engineer" the Sinusoidal position encoding and provide other choices for $\theta_i$. But remember, up to now, our derivation has been based on the simple case where $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}=\boldsymbol{I}$. For a general $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}$, does using the above Sinusoidal position encoding still preserve these good properties?

If $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}$ is a diagonal matrix, then the various properties above can be somewhat preserved. In this case:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{p}_m^{\top} \boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}} \boldsymbol{p}_n=\sum_{i=1}^{d/2} \boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}_{2i,2i} \cos m\theta_i \cos n\theta_i + \boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}_{2i+1,2i+1} \sin m\theta_i \sin n\theta_i\end{equation}

Using the product-to-sum identities, we get:

\begin{equation}\sum_{i=1}^{d/2} \frac{1}{2}\left(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}_{2i,2i} + \boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}_{2i+1,2i+1}\right) \cos (m-n)\theta_i + \frac{1}{2}\left(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}_{2i,2i} - \boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}_{2i+1,2i+1}\right) \cos (m+n)\theta_i \end{equation}

We can see that it indeed contains the relative position $m-n$, although it might also include the $m+n$ term. If it is not needed, the model can let $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}_{2i,2i} = \boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}_{2i+1,2i+1}$ to eliminate it. In this special case, we point out that Sinusoidal position encoding grants the model the possibility to learn relative positions; as for which specific position information is needed, that is determined by the model's own training.

In particular, for the above equation, the long-range decay property still exists. Take the first sum, for example. Analogous to the approximation in the previous section, it is equivalent to the integral:

\begin{equation}\sum_{i=1}^{d/2} \frac{1}{2}\left(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}_{2i,2i} + \boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}_{2i+1,2i+1}\right) \cos (m-n)\theta_i \sim \int_0^1 h_t e^{\text{i}(m-n)\theta_t}dt\end{equation}

Similarly, results from the estimation of oscillatory integrals (ref: "Oscillatory integrals", "Study Notes 3 - One-dimensional Oscillatory Integrals and Applications", etc.) tell us that under easily achievable conditions, the integral value tends toward zero as $|m-n|\to\infty$. Therefore, the long-range decay property can be preserved.

If $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}$ is not a diagonal matrix, then unfortunately, the above properties are difficult to reproduce. We can only hope that the diagonal part of $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}$ is dominant, so that the properties can be approximately preserved. The diagonal part being dominant means that the correlation between any two dimensions of the $d$-dimensional vector is small, satisfying a degree of decoupling. For an Embedding layer, this assumption has some rationality. I tested the covariance matrices of the word embedding and position embedding matrices trained by BERT and found that the diagonal elements are significantly larger than the non-diagonal elements, proving that the assumption that the diagonal part is dominant is somewhat reasonable.

Problem Discussion

Some readers may argue: even if you describe Sinusoidal position encoding as peerless, it doesn't change the fact that directly trained position encodings perform better than Sinusoidal position encoding. Indeed, experiments have shown that in models like BERT that have undergone sufficient pre-training, directly trained position encodings are slightly better than Sinusoidal position encoding. I do not deny this. What this article aims to do is to start from some principles and assumptions to deduce why Sinusoidal position encoding can serve as an effective position encoding, but not to say it is necessarily the best.

Derivations are based on assumptions. If the derived result is not good enough, it means the assumptions do not sufficiently match reality. So, for Sinusoidal position encoding, where might the problems lie? We can reflect step by step.

Step one: Taylor expansion. This depends on $\boldsymbol{p}$ being small. I also verified this in BERT and found that the average norm of word embeddings is larger than that of position embeddings, which suggests that assuming $\boldsymbol{p}$ is small is reasonable to some extent, but how reasonable is hard to say because while the embedding norm is larger, it's not overwhelming. Step two: assuming $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{H}}$ is the identity matrix. Since we analyzed in the previous section that the diagonal is likely dominant, assuming identity might not be too big of an issue. Step three: assuming relative position is expressed through the inner product of two absolute position vectors. Intuition tells us this should be reasonable; the interaction of absolute positions should be capable of expressing relative position information. Final step: determining $\theta_i$ through the property of automatic long-range decay. This should be a good thing, but this step has the most variables because there are too many optional forms for $\theta_i$, and even trainable $\theta_i$. It is difficult to choose the most reasonable one. Therefore, if Sinusoidal position encoding is not good enough, this step is very much worth re-examining.

Article Summary

In summary, this article attempts to derive Sinusoidal position encoding based on several assumptions. These assumptions have their own rationality as well as some issues, making the Sinusoidal position encoding noteworthy yet not flawless. Regardless, in current deep learning, being able to obtain an explicit solution for a specific problem rather than directly using brute-force fitting makes Sinusoidal position encoding a rare and precious case worthy of deep reflection.

Jianlin Su. (Mar. 08, 2021). "Transformer Upgrade Road: 1. Tracing the Origins of Sinusoidal Position Encoding" [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://kexue.fm/archives/8231