By 苏剑林 | April 03, 2021

In a previous article, "Is GPT-3 Necessary? No, BERT's MLM Model Can Also Do Small-Shot Learning," we introduced a method called Pattern-Exploiting Training (PET). By combining manually constructed templates with BERT's MLM (Masked Language Model), it can achieve excellent results in zero-shot, small-shot, and even semi-supervised learning. This approach is elegant because it unifies the pre-training task with downstream tasks. However, manually constructing these templates can sometimes be difficult, and the effectiveness of different templates varies greatly. If templates could be automatically constructed using a small number of samples, it would be highly valuable.

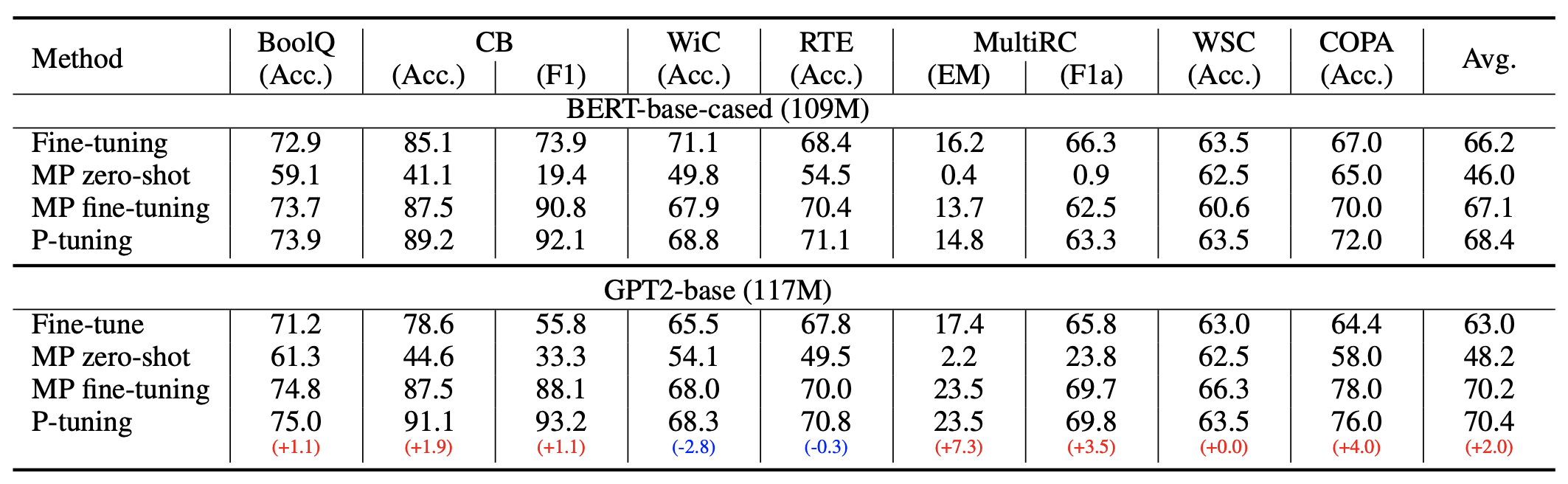

A recent paper on Arxiv, "GPT Understands, Too," proposed a method called P-tuning, which successfully realizes the automatic construction of templates. Not only that, but with the help of P-tuning, GPT's performance on SuperGLUE exceeded that of BERT models of the same class for the first time. This overturns the long-held conclusion that "GPT is not good at NLU" (Natural Language Understanding), which is the reason for the paper's title.

What is a Template

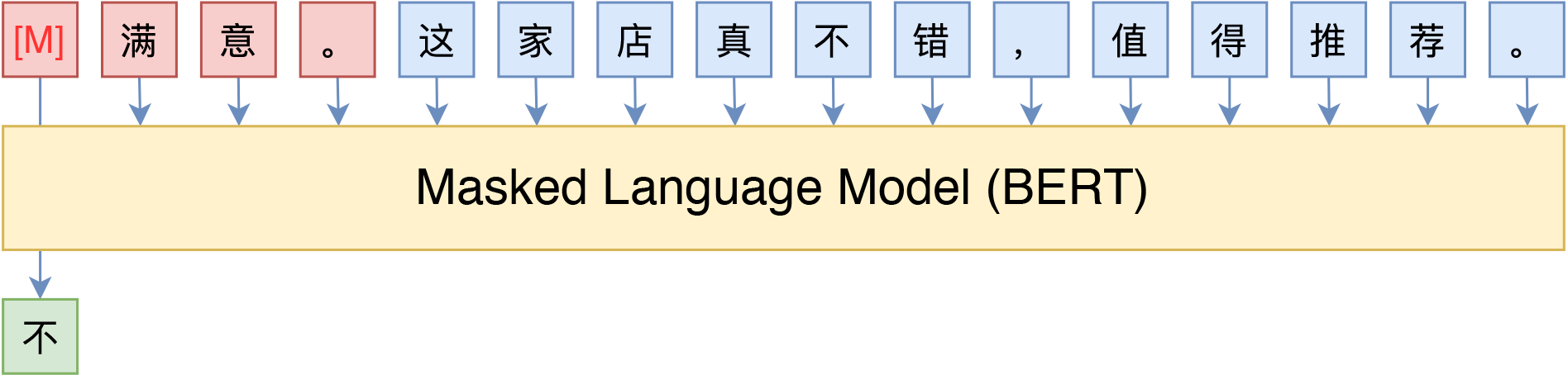

The main idea of PET is to use templates (often called Patterns or Prompts) composed of natural language to transform a downstream task into a cloze task. This allows a BERT MLM model to be used for prediction. For example, the image below shows sentiment classification and topic classification using conditional prefixes:

Translating sentiment classification to an MLM task via specific templates

Translating news classification to an MLM task via specific templates

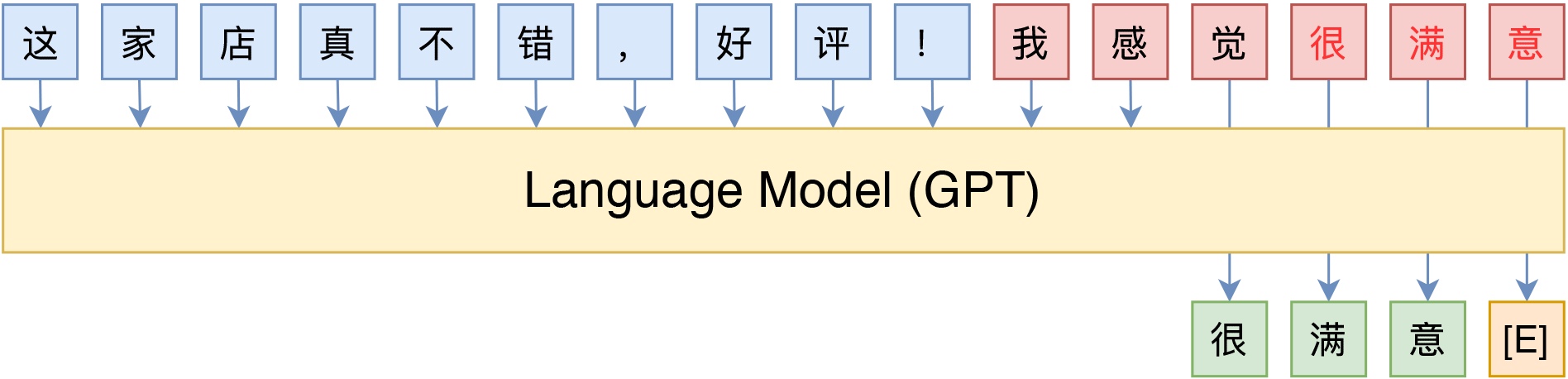

Of course, this scheme is not only limited to MLM models; using unidirectional language models (LM) like GPT is also straightforward:

Translating sentiment classification to an LM task via specific templates

Translating news classification to an LM task via specific templates

However, since language models decode from left to right, the prediction part must be placed at the end of the sentence (although categorical prefixes can be added, the predicted portion remains at the end).

In a sense, these templates act as "probes" for the language model. We can extract specific knowledge from the language model through these templates, achieving good zero-shot effects. Combined with a small number of labeled samples, the performance can be further improved, as discussed in detail in "Is GPT-3 Necessary? No, BERT's MLM Model Can Also Do Small-Shot Learning."

However, as mentioned, for some tasks, constructing templates manually is not easy. We cannot easily determine the quality of a template, and the difference in performance between different models can be massive. In such cases, manually labeling a few samples might be easier than constructing a template. Therefore, how to automatically build a template based on existing labeled samples has become a problem worth studying.

P-tuning

P-tuning re-examines the definition of a template and abandons the conventional requirement that "templates must consist of natural language." It converts the construction of templates into a continuous parameter optimization problem, which is simple yet effective.

Rethinking Templates

First, let's think about "what a template is." Intuitively, a template is a prefix/suffix composed of natural language. Through these templates, we align the downstream task with the pre-training task, allowing more full utilization of the original pre-trained model and resulting in better zero-shot and small-shot learning.

But wait, do we really care if the template is made of "natural language"?

Not really. Essentially, we don't care what the template looks like; we only need to know which tokens it consists of, where to insert them, whether they help complete our downstream task after insertion, and what the candidate space for the output is. Whether the template is natural language or not has no impact on us. The "natural language" requirement is only to better achieve "consistency," but it is not mandatory. Thus, P-tuning considers templates of the following form:

![P-tuning uses [unused*] tokens directly to build templates](https://kexue.fm/usr/uploads/2021/04/2868831073.png)

P-tuning directly uses [unused*] tokens to build templates, ignoring the natural language aspect of the template.

Here, [u1] to [u6] represent the [unused1] to [unused6] tokens in the BERT vocabulary. That is, several tokens never seen before are used to form the template. The number of tokens is a hyperparameter, and whether they are placed at the beginning or the end can also be adjusted. Then, to make the "template" work, we use labeled data to solve for this template.

How to Optimize

At this point, depending on the amount of labeled data, we discuss two scenarios.

First, the labeled data is scarce. In this case, we fix the weights of the entire model and only optimize the Embeddings of the [u1] to [u6] tokens. In other words, we are essentially learning six new Embeddings that act as a template. Since the model weights are almost entirely fixed, training is very fast. Because there are so few parameters to learn, even with very few labeled samples, the template can be learned without easy overfitting.

Second, the labeled data is sufficient. In this case, if we still followed the first scenario, underfitting would occur because the six tokens provide too few optimizable parameters. Therefore, we can open all weights for fine-tuning. The experiments in the original paper on SuperGLUE were done this way. Readers might think: What is the difference between this and directly adding a full connection layer for fine-tuning? The original paper's results show that this approach works better, likely because it is more consistent with the pre-training task.

Performance of P-tuning on SuperGLUE

Furthermore, in the example above, target tokens such as "Very" or "Sports" are manually selected. Can they also be replaced by [unused*] tokens? The answer is yes, but it also falls into two cases: 1. When labeled data is scarce, manually selecting appropriate target tokens often works better; 2. When labeled data is sufficient, using [unused*] for target tokens works better because the model's optimization space is larger.

Enhancing Correlation

In the original paper, P-tuning doesn't just randomly initialize several new tokens and train them directly. Instead, these Embeddings are calculated through a small LSTM model, and this LSTM model is made learnable. What's the benefit of this extra step? The original paper suggests that token representations appearing in an LSTM have stronger correlations, which to some extent makes them more like "natural language" (since natural language tokens are not independent). Additionally, it prevents falling into local optima. I confirmed with the author on GitHub (refer here) that the difference in effect is that the LSTM approach allows the model to converge faster and achieve better results.

However, adding an LSTM feels a bit awkward and slightly complicates implementation. According to the author, the LSTM helps the template tokens become (to some extent) closer to natural language. But this doesn't necessarily require an LSTM, and even if an LSTM is used, it might not achieve this. I believe a more natural method is that while training for the downstream task, we should not only predict the target token (e.g., "Very" or "News") but also predict other tokens simultaneously.

For example, if it's an MLM model, randomly mask other tokens for prediction as well. If it's an LM model, predict the complete sequence rather than just the target word. The reasoning is: since our MLM/LM are pre-trained on natural language, we (perhaps overconfidently) believe that sequences that can be reconstructed well must be close to natural language. Therefore, adding such auxiliary training objectives can also make the model closer to natural language. My testing shows that adding such auxiliary objectives does improve performance compared to only optimizing the downstream task objective.

Experiments and Effects

As the saying goes, "talk is cheap, show me the code." It's time for the experiments. Here, I'll share the experimental results of P-tuning, including my implementation logic and experimental results on Chinese tasks.

Stopped Gradients

What is the best way to implement the P-tuning algorithm? If all weights are released for training, it is simple and no different from ordinary BERT fine-tuning. The key is how to implement "optimizing only a few tokens" in a small-shot scenario.

There are several methods, such as re-constructing an Embedding layer for the tokens to be optimized, concatenating it with the BERT Embedding layer, and then only releasing weights for the new Embedding layer during training. But this requires significant changes to the original code. The best way is to minimize code changes so that it is almost transparent to the user. To this end, I devised a scheme to modify the Embedding layer using stop_gradient, roughly as follows:

class PtuningEmbedding(Embedding):

"""New Embedding layer that optimizes only specific Tokens"""

def call(self, inputs, mode='embedding'):

embeddings = self.embeddings

embeddings_sg = K.stop_gradient(embeddings)

mask = np.zeros((K.int_shape(embeddings)[0], 1))

mask[1:9] += 1 # Only optimize tokens with ids 1 to 8

self.embeddings = embeddings * mask + embeddings_sg * (1 - mask)

return super(PtuningEmbedding, self).call(inputs, mode)

After a variable passes through the stop_gradient operator, its gradient is zero during backpropagation, but forward propagation remains unchanged. Therefore, in the code above, the forward propagation results won't change, but when calculating gradients during backpropagation, the gradients of the tokens controlled by the mask will be non-zero, while the gradients of all other tokens will be zero. This achieves updating only specific tokens.

The complete code is available at:

GitHub: https://github.com/bojone/P-tuning

By the way, the original paper also released code:

GitHub: https://github.com/THUDM/P-tuning

Testing and Effects

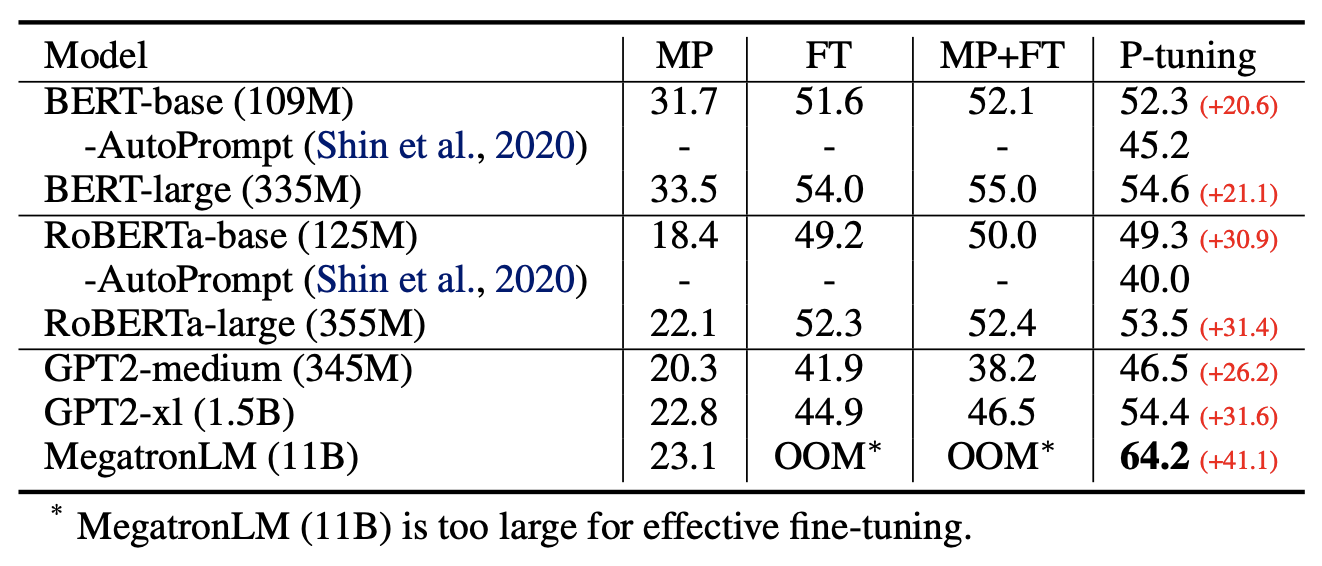

I previously shared the original author's experimental results on SuperGLUE, which showed that with P-tuning: 1. The performance of GPT and BERT improved significantly compared to direct fine-tuning; 2. GPT's performance could even exceed BERT's. This indicates that GPT not only has NLG (Natural Language Generation) capabilities but also NLU capabilities, essentially "squeezing" out GPT's potential. Of course, BERT also improved with P-tuning, indicating that P-tuning's release of language model potential is relatively universal.

The original paper has rich experiments, and I recommend readers read it carefully; it is very rewarding. Notably, in Table 2 of the final column, when the pre-trained model is large enough, our devices might not be able to fine-tune the entire model. P-tuning can choose to optimize only a few token parameters, which significantly reduces the memory and computing power required for optimization. Thus, P-tuning actually gives us a way to utilize large-scale pre-trained models within limited computing power.

Effect of P-tuning across various language model sizes

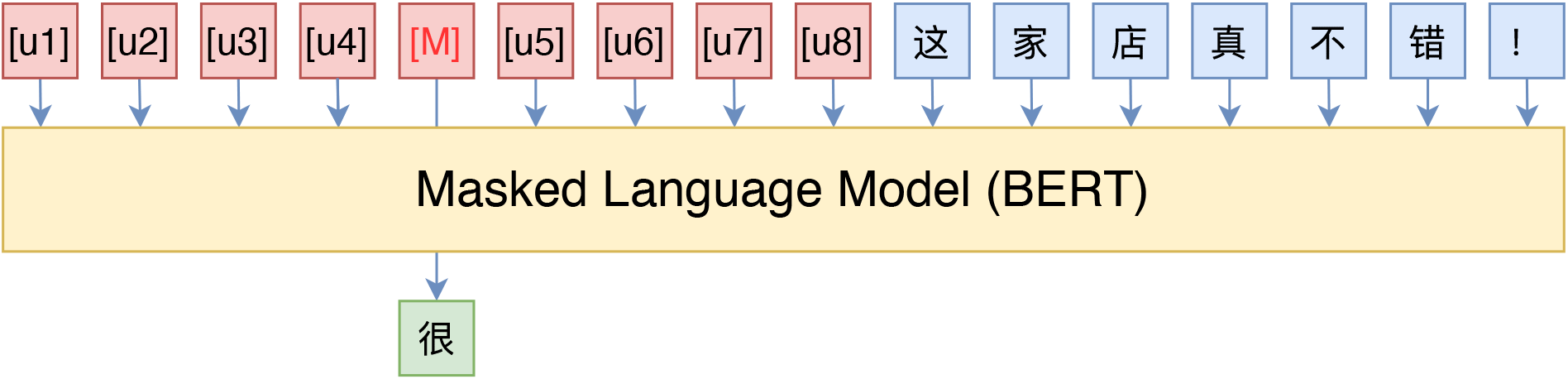

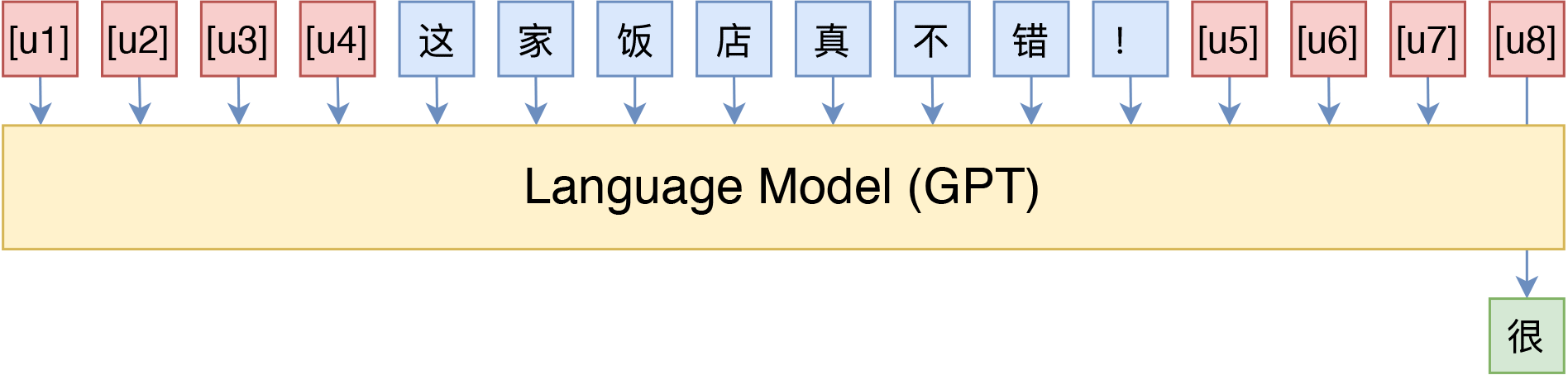

Of course, my consistent view is that "an algorithm not tested on Chinese has no soul." Therefore, I also briefly tested it on Chinese tasks. The test task is consistent with "Is GPT-3 Necessary? No, BERT's MLM Model Can Also Do Small-Shot Learning," involving small-shot sentiment classification. The test models included BERT and GPT, with their respective candidate templates shown below:

The "BERT + P-tuning" template I used for Chinese sentiment classification

The "GPT + P-tuning" template I used for Chinese sentiment classification

Note that for LM models, introducing a prefix is very important; the effect is significantly worse when only a suffix is introduced. For MLM models, the prefix effect is also generally better than the suffix. The overall results are in the table below:

\[

\begin{array}{c|cc}

\hline

& \text{Validation Set} & \text{Test Set} \\

\hline

\text{Small-shot Direct Fine-tuning} & 88.93\% & 89.34\% \\

\text{VAT Semi-supervised Learning} & 89.83\% & 90.37\% \\

\hline

\text{PET Zero-shot} & 85.17\% & 84.27\% \\

\text{PET Unsupervised} & 88.05\% & 87.53\% \\

\text{PET Small-shot} & 89.29\% & 89.18\% \\

\text{PET Semi-supervised} & 90.09\% & 89.76\% \\

\hline

\text{BERT + P-tuning} & 89.81\% & 89.75\% \\

\text{GPT + P-tuning} & 89.30\% & 88.51\% \\

\hline

\end{array}

\]

Among these, "Small-shot" uses only a "small number of labeled samples," "Unsupervised" uses "a large amount of unlabeled samples," "Semi-supervised" uses "a small number of labeled samples + a large amount of unlabeled samples," and "P-tuning" are all small-shot experiments. PET tasks report the best results from manual templates, although there were worse ones. From a small-shot perspective, P-tuning indeed achieved the best results. From a template construction perspective, P-tuning is indeed much better than manually constructed templates. From the model perspective, P-tuning can indeed bring GPT's classification performance close to BERT, revealing the fact that GPT also has strong NLU capabilities.

Further Understanding

This section introduces my further thoughts on P-tuning, aiming to understand it from multiple dimensions.

Discrete vs. Continuous

Before P-tuning, there were already some efforts in automatic template construction, such as "How Can We Know What Language Models Know?" and "AutoPrompt: Eliciting Knowledge from Language Models with Automatically Generated Prompts." However, they searched for natural language templates in a discrete space, so their effectiveness was limited and did not yield particularly prominent results.

In contrast, P-tuning abandoned the requirement of "natural language," turning it into a continuous parameter problem that can be solved by simple gradient descent. The result is better. At the same time, this change means P-tuning highlights the essence of a template—that the key lies in how it's used, not what it consists of—giving a sense of "extracting the essence" that is indeed commendable.

(Note: As pointed out by reader @brotherb, the paper "Prefix-Tuning: Optimizing Continuous Prompts for Generation" published at the beginning of the year is quite close to P-tuning. Both designed non-natural language templates, though Prefix-Tuning mainly focuses on NLG applications while P-tuning focuses more on NLU.)

Adapter

We can also understand P-tuning from the perspective of an Adapter. Shortly after BERT was released, Google proposed a fine-tuning method called Adapter in the paper "Parameter-Efficient Transfer Learning for NLP." It doesn't fine-tune the entire model directly. Instead, it fixes the original BERT weights and adds some residual modules on top of BERT, optimizing only these residual modules. Since these modules have fewer parameters, the fine-tuning cost is lower. The idea of the Adapter actually originates from CV's "Learning multiple visual domains with residual adapters." However, it hasn't been seen much in the last two years, perhaps because while it improves training speed, it decreases prediction speed and often results in some loss of accuracy.

In P-tuning, if we don't treat the new tokens as "templates" but as part of the model, then P-tuning is actually a type of Adapter approach. It also fixes the original model weights and inserts new optimizable parameters, updating only these new parameters. The difference is that the new parameters are inserted into the Embedding layer. Therefore, from this perspective, P-tuning and Adapters share many similarities.

Why is it Effective?

Now, there's another question worth considering: Why is P-tuning better? For example, with full data, everyone opens all weights, yet P-tuning is still better than direct fine-tuning. Why?

In fact, readers who ask this question are likely "used to" the practice of adding a full connection layer on top of BERT for fine-tuning. Obviously, whether it is PET or P-tuning, they are closer to the pre-training task, while the practice of adding a full connection layer is not as close. So in a sense, the effectiveness of P-tuning is more "obvious," and it is the effectiveness of adding a full connection layer that should be questioned.

Last year, the paper "A Mathematical Exploration of Why Language Models Help Solve Downstream Tasks" attempted to answer this. The general line of reasoning is:

- The pre-trained model is a certain type of language model task;

- Downstream tasks can be expressed as a special case of this language model;

- When the output space is finite, it approximates adding a full connection layer;

- Therefore, fine-tuning with an added full connection layer is effective.

As can be seen, the paper's main assumption is point 2, which effectively assumes that downstream tasks can be expressed in a format similar to PET and then proceeds to prove it. This further illustrates that PET and P-tuning are more natural ways to use pre-trained models. Fine-tuning by adding a full connection layer is just a corollary of them. In other words, PET and P-tuning are schemes that return to the essence, which is why they are more effective.

Simple Summary

This article introduced P-tuning, an automatic template construction method. Through templates, we can extract knowledge from language models and complete tasks such as zero-shot and small-shot learning with often superior effects. With P-tuning, GPT can achieve excellent NLU results, even surpassing BERT on SuperGLUE. Additionally, P-tuning provides an effective solution for utilizing large pre-trained models under limited computing resources.