By 苏剑林 | Oct 22, 2021

As the name suggests, this article introduces a post-processing technique for classification problems—CAN (Classification with Alternating Normalization), from the paper "When in Doubt: Improving Classification Performance with Alternating Normalization". According to my tests, CAN indeed improves performance in most multi-class classification scenarios, and it adds almost no predictive cost, as it involves simple re-normalization operations on the prediction results.

Interestingly, the core idea behind CAN is very rustic—so rustic that everyone probably uses similar logic in daily life. However, the original CAN paper did not explain this idea very clearly, instead focusing on formal introductions and experiments. In this post, I will try to explain the algorithmic logic clearly.

Suppose we have a binary classification problem. For input $a$, the model's prediction is $p^{(a)} = [0.05, 0.95]$, so we predict class $1$. Next, for input $b$, the model gives $p^{(b)} = [0.5, 0.5]$. At this point, the model is in a state of maximum uncertainty, and we don't know which class to output.

However, what if I told you: 1. The class must be either 0 or 1; 2. The probability of each class occurring is exactly 0.5. Given these two pieces of prior information, since the previous sample was predicted as class 1, based on a naive principle of "balance," wouldn't we be more inclined to predict the second sample as class 0 to satisfy the second prior?

There are many such examples. For instance, if you are taking a 10-question multiple-choice test, you are confident about the first 9 questions. For the 10th question, you have no idea and have to guess. If you look back and see that among the first 9 questions, you've chosen A, B, and C, but never D, would you be more inclined to choose D for your guess?

Behind these simple examples lies the same logic as CAN: it uses prior distributions to calibrate low-confidence predictions, making the distribution of the new predictions closer to the prior distribution.

To be precise, CAN is a post-processing method targeting low-confidence predictions. Therefore, we first need a metric to measure the uncertainty of a prediction. A common measure is "Entropy" (refer to "Can't Afford 'Entropy': From Entropy and the Maximum Entropy Principle to Maximum Entropy Models (I)"). For $p=[p_1, p_2, \cdots, p_m]$, it is defined as:

\begin{equation}H(p) = -\sum_{i=1}^m p_i \log p_i\end{equation}However, although entropy is a common choice, its results do not always align with our intuition. For example, for $p^{(a)}=[0.5, 0.25, 0.25]$ and $p^{(b)}=[0.5, 0.5, 0]$, applying the formula directly yields $H(p^{(a)}) > H(p^{(b)})$. But for our classification scenario, we would clearly consider $p^{(b)}$ to be more "uncertain" than $p^{(a)}$ (regarding the top candidates), so simply using entropy is not reasonable enough.

A simple fix is to calculate the entropy using only the top-$k$ probability values. Without loss of generality, assume $p_1, p_2, \cdots, p_k$ are the highest $k$ values; then:

\begin{equation}H_{\text{top-}k}(p) = -\sum_{i=1}^k \tilde{p}_i \log \tilde{p}_i\end{equation}where $\tilde{p}_i = p_i \Big/ \sum_{i=1}^k p_i$. To get a result in the range of 0 to 1, we use $H_{\text{top-}k}(p) / \log k$ as the final uncertainty metric.

Now suppose we have $N$ samples to predict. The model directly outputs $N$ probability distributions $p^{(1)}, p^{(2)}, \cdots, p^{(N)}$. Assuming the test samples and training samples are identically distributed, a perfect set of predictions should satisfy:

\begin{equation}\frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^N p^{(i)} = \tilde{p}\label{eq:prior}\end{equation}where $\tilde{p}$ is the prior distribution of classes, which we can estimate directly from the training set. That is, the average of all predictions should be consistent with the prior distribution. However, due to model performance limitations, the actual prediction results may deviate significantly from the equation above. In such cases, we can manually correct this part.

Specifically, we select a threshold $\tau$. Predictions with an uncertainty metric below $\tau$ are treated as high-confidence, while those greater than or equal to $\tau$ are low-confidence. Without loss of generality, assume the first $n$ results $p^{(1)}, p^{(2)}, \cdots, p^{(n)}$ are high-confidence, and the remaining $N-n$ are low-confidence. We believe the high-confidence part is more reliable, so it doesn't need correction, and it can serve as a "standard reference frame" to correct the low-confidence part.

Specifically, for each $j \in \{n+1, n+2, \cdots, N\}$, we take $p^{(j)}$ along with the high-confidence $p^{(1)}, p^{(2)}, \cdots, p^{(n)}$ and perform one **"Inter-row" normalization**:

\begin{equation}p^{(k)} \leftarrow p^{(k)} \big/ \bar{p} \times \tilde{p}, \quad \bar{p} = \frac{1}{n+1} \left( p^{(j)} + \sum_{i=1}^n p^{(i)} \right) \label{eq:step-1}\end{equation}where $k \in \{1, 2, \cdots, n\} \cup \{j\}$, and the multiplication/division are element-wise. It is easy to see that the purpose of this normalization is to make the mean vector of all new $p^{(k)}$ equal to the prior distribution $\tilde{p}$, encouraging Eq. $\eqref{eq:prior}$ to hold. However, after this normalization, each $p^{(k)}$ might no longer be a valid probability distribution (summing to 1), so we must perform an **"Intra-row" normalization**:

\begin{equation}p^{(k)} \leftarrow \frac{p^{(k)}_i}{\sum_{i=1}^m p^{(k)}_i} \label{eq:step-2}\end{equation}But doing this might break Eq. $\eqref{eq:prior}$ again. Therefore, theoretically, we can iterate these two steps until convergence (though experiments show that usually one iteration yields the best results). Finally, we only keep the updated $p^{(j)}$ as the prediction result for the $j$-th sample, discarding the other $p^{(k)}$.

Note that this process needs to be executed for each low-confidence result $j \in \{n+1, n+2, \cdots, N\}$; that is, it is a sample-by-sample correction, not a batch correction. Each $p^{(j)}$ is corrected using the **original** high-confidence results $p^{(1)}, p^{(2)}, \cdots, p^{(n)}$. Although $p^{(1)}, p^{(2)}, \cdots, p^{(n)}$ are updated during the iterations, those are temporary results and are discarded; every correction starts from the original $p^{(1)}, p^{(2)}, \cdots, p^{(n)}$.

Below is a reference implementation code provided by the author:

# Prediction results, calculate accuracy before correction

y_pred = model.predict(

valid_generator.fortest(), steps=len(valid_generator), verbose=True

)

y_true = np.array([d[1] for d in valid_data])

acc_original = np.mean([y_pred.argmax(1) == y_true])

print('original acc: %s' % acc_original)

# Evaluate the uncertainty of each prediction

k = 3

y_pred_topk = np.sort(y_pred, axis=1)[:, -k:]

y_pred_topk /= y_pred_topk.sum(axis=1, keepdims=True)

y_pred_uncertainty = -(y_pred_topk * np.log(y_pred_topk)).sum(1) / np.log(k)

# Select threshold, split into high and low confidence parts

threshold = 0.9

y_pred_confident = y_pred[y_pred_uncertainty < threshold]

y_pred_unconfident = y_pred[y_pred_uncertainty >= threshold]

y_true_confident = y_true[y_pred_uncertainty < threshold]

y_true_unconfident = y_true[y_pred_uncertainty >= threshold]

# Display accuracy for both parts

# Generally, accuracy for the high-confidence set is much higher than the low-confidence one

acc_confident = (y_pred_confident.argmax(1) == y_true_confident).mean()

acc_unconfident = (y_pred_unconfident.argmax(1) == y_true_unconfident).mean()

print('confident acc: %s' % acc_confident)

print('unconfident acc: %s' % acc_unconfident)

# Estimate prior distribution from training set

prior = np.zeros(num_classes)

for d in train_data:

prior[d[1]] += 1.

prior /= prior.sum()

# Correct low-confidence samples one by one and re-evaluate accuracy

right, alpha, iters = 0, 1, 1

for i, y in enumerate(y_pred_unconfident):

Y = np.concatenate([y_pred_confident, y[None]], axis=0)

for j in range(iters):

Y = Y**alpha

Y /= Y.mean(axis=0, keepdims=True)

Y *= prior[None]

Y /= Y.sum(axis=1, keepdims=True)

y = Y[-1]

if y.argmax() == y_true_unconfident[i]:

right += 1

# Output final accuracy after correction

acc_final = (acc_confident * len(y_pred_confident) + right) / len(y_pred)

print('new unconfident acc: %s' % (right / (i + 1.)))

print('final acc: %s' % acc_final)

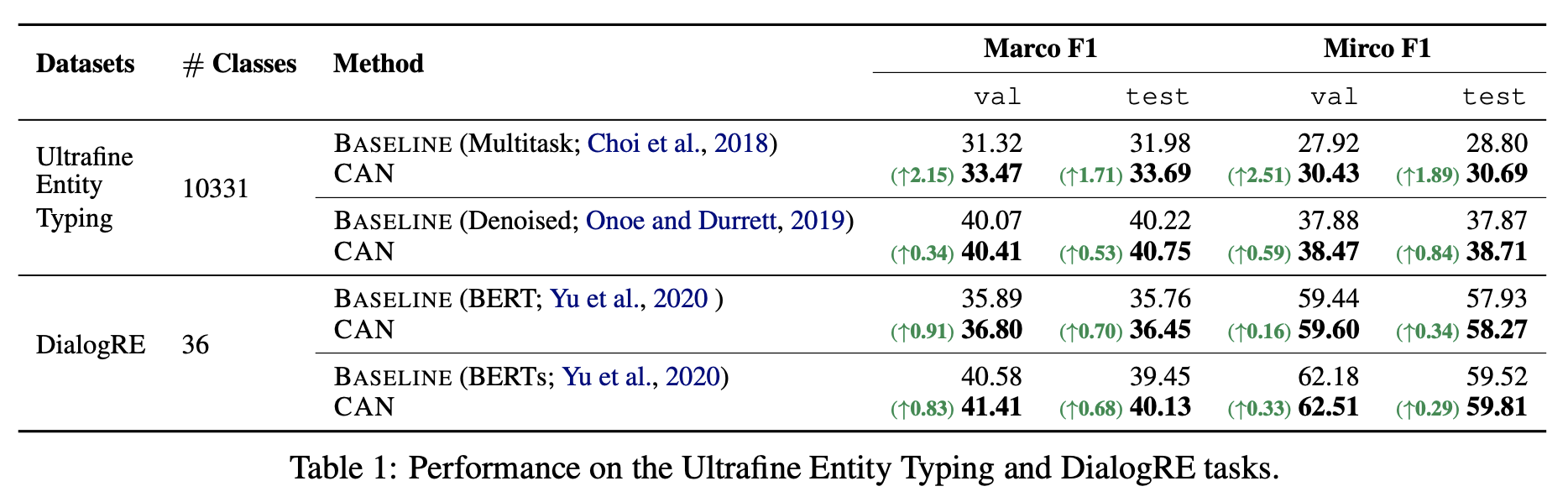

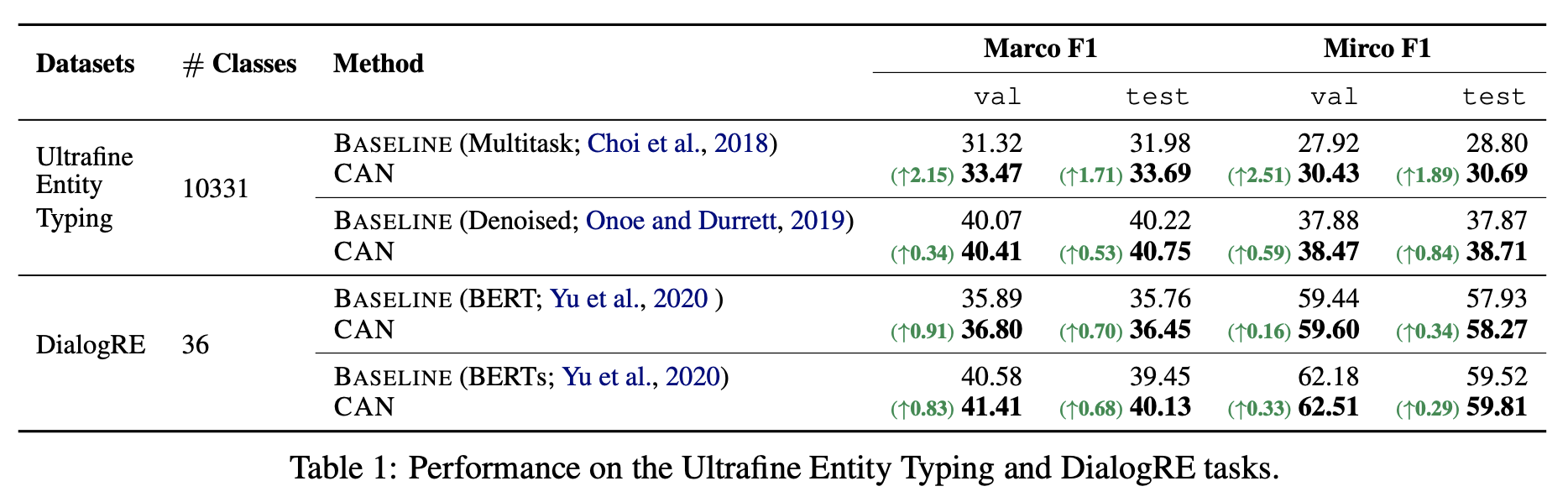

How much improvement can such a simple post-processing trick bring? the results provided in the original paper are quite impressive:

One of the experimental results from the original paper

I also conducted experiments on two Chinese text classification tasks from CLUE, which showed a small boost (validation set results):

\begin{array}{c|c|c} \hline & \text{IFLYTEK (Classes: 119)} & \text{TNEWS (Classes: 15)} \\ \hline \text{BERT} & 60.06\% & 56.80\% \\ \text{BERT + CAN} & 60.52\% & 56.86\% \\ \hline \text{RoBERTa} & 60.64\% & 58.06\% \\ \text{RoBERTa + CAN} & 60.95\% & 58.00\% \\ \hline \end{array}Overall, the more classes there are, the more significant the improvement. If the number of classes is small, the improvement might be minimal or even lead to a slight decrease (though the drop is usually marginal), making this a "nearly free lunch." As for hyperparameter selection, in the Chinese results above, I only iterated once, chose $k=3$ and $\tau=0.9$. After simple tuning, this combination seems to be optimal.

Some readers might wonder if the assumption that "high-confidence results are more reliable" actually holds true. At least in my two Chinese experiments, it was clearly true. For example, in the IFLYTEK task, the accuracy of the selected high-confidence set was 0.63+, while the low-confidence set was only 0.22+. Similarly for TNEWS, the high-confidence set accuracy was 0.58+, while the low-confidence set was only 0.23+.

Finally, let's reflect and evaluate CAN systematically.

First, a natural question is: why not batch all low-confidence results with high-confidence results for correction instead of doing it one by one? I don't know if the original authors compared these, but I tested it. The results showed that batch correction sometimes matched sample-by-sample correction but sometimes caused a decline. This makes sense: CAN's intent is to use the prior distribution combined with "known high-confidence samples" to correct the "unknown." If too many low-confidence results are merged into the process at once, the cumulative bias might increase, making sample-by-sample correction theoretically more reliable.

Speaking of the original paper, readers who have read it might notice three differences between my introduction and the paper:

1. **Calculation method for the uncertainty metric.** According to the paper's description, the final uncertainty calculation should be:

\begin{equation}-\frac{1}{\log m}\sum_{i=1}^k p_i \log p_i\end{equation}That is, it also uses a top-$k$ entropy form, but it does not re-normalize the $k$ probability values, and the factor used to compress the result into the 0-1 range is $\log m$ instead of $\log k$ (because without re-normalization, only dividing by $\log m$ ensures the output stays between 0 and 1). My tests showed that the paper's method often results in values significantly smaller than 1, which makes finding and tuning a threshold unintuitive.

2. **Presentation style of CAN.** The paper presented the algorithm steps in a purely mathematical and matrix-oriented way without explaining the underlying ideology, which isn't very user-friendly. Without thinking deeply about the principle, it is hard to understand why such post-processing works. Once understood, it feels a bit like "mystification."

3. **Algorithmic flow variation.** The original paper introduced a parameter $\alpha$ during iteration, turning Eq. $\eqref{eq:step-1}$ into:

\begin{equation}p^{(k)} \leftarrow [p^{(k)}]^{\alpha} \big/ \bar{p} \times \tilde{p}, \quad \bar{p} = \frac{1}{n+1} \left( [p^{(j)}]^{\alpha} + \sum_{i=1}^n [p^{(i)}]^{\alpha} \right)\end{equation}essentially raising each result to the power of $\alpha$ before iteration. The paper didn't explain this either. In my view, this parameter is purely for tuning (more parameters allow for higher scores). In my experiments, $\alpha=1$ was pretty much optimal, and fine-tuning $\alpha$ yielded no substantial gains.

This article introduced a simple post-processing trick called CAN. It leverages the prior distribution to re-normalize predictions, improving classification performance with almost zero extra computation. My experiments show that CAN indeed brings benefits, especially when the number of classes is high.