Standard event extraction sample (Image from Baidu DuEE's GitHub)

By Su Jianlin | Feb 21, 2022 | Information Age

About two years ago, I first encountered the event extraction task in Baidu's "2020 Language and Intelligent Technology Competition." In the article "bert4keras in hand, I have the baseline: Baidu LIC2020," I shared a simple baseline that converted it into NER using BERT+CRF. However, that baseline was more of a placeholder—a semi-finished product—and could not be called a complete event extraction model. Over the past two years, while relation extraction models have emerged one after another with SOTA results constantly being updated, event extraction has not seen many particularly brilliant designs.

Recently, I revisited the event extraction task. Building upon my previous relation extraction model GPLinker, and combining it with complete subgraph searching, I designed a relatively simple but comprehensive joint event extraction model, which I still call GPLinker. I invite everyone to comment on it.

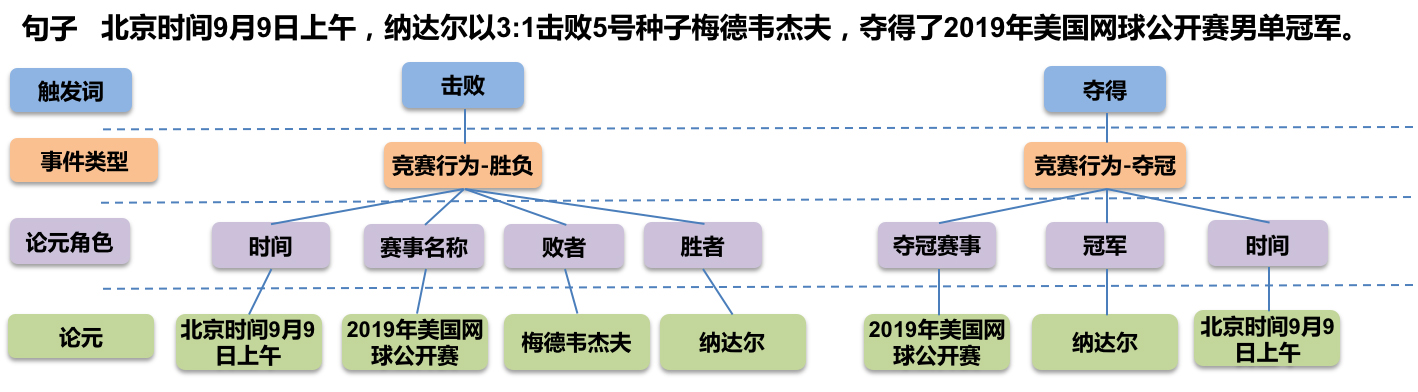

Event extraction is a comprehensive task. A standard event extraction sample is as follows:

Standard event extraction sample (Image from Baidu DuEE's GitHub)

Each event has an event type and a corresponding trigger word, along with arguments playing different roles. Event types and argument roles are selected from a predefined limited set (schema), while trigger words and arguments are generally fragments of the input sentence. In a few cases, they might be categorical objects from an enumerable set (this appeared in Baidu's DuEE-fin). In principle, the design of an event extraction model depends on the evaluation metrics. In LIC2020, the reason we could convert event extraction into an NER problem was that the evaluation metrics at the time only examined the triples composed of (event type, argument role, argument). Thus, we could combine (event type, argument role) into a single large class, mapping it directly to NER.

Of course, this was just an opportunistic approach for that specific metric. For real-world event extraction scenarios, we naturally hope to extract events in a standard format, which means designing a model that is as complete as possible. Below, I will introduce the GPLinker model we use for event extraction, which basically achieves the requirement of being both simple and complete.

We have mentioned the word "complete" several times. What does it mean? Specifically, we want the final model design to be theoretically applicable to as many event extraction scenarios as possible. Traditional event extraction models are generally divided into four subtasks: "trigger detection," "event/trigger type identification," "event argument detection," and "argument role identification." This means the trigger must be detected first, and further processing is based on the trigger. If the training set does not have triggers labeled, it cannot be done, which shows the traditional approach is not complete enough.

To unify scenarios with and without triggers, we treat the trigger word as just another argument role of the event. Thus, having or not having a trigger is simply a matter of adding or removing an argument, so the primary focus remains on argument identification and event division. For argument identification, we still combine (event type, argument role) into a large class and convert it into an NER problem. However, it should be noted that different entities may overlap/nest, so the previous CRF-based NER is insufficient. We use GlobalPointer, which can identify nested entities, to accomplish this.

As mentioned earlier, tasks like DuEE-fin also include classification-style argument types, where the argument is not a fragment of the input text but is 1 choice from a limited set. Since there are not many such argument types, we convert them into extraction-style arguments. Using DuEE-fin as an example, the "Step" argument for the "Company Listing" event type has four candidate values: Listing Preparation, Listing Suspension, Formal Listing, and Listing Termination. Instead of treating "Step" as an argument type, we treat Listing Preparation, Listing Suspension, Formal Listing, and Listing Termination as four distinct argument types, with the corresponding entity being the trigger word. Thus, the argument we extract is not a categorical (Company Listing, Step, XX Listing), but an extractive (Company Listing, XX Listing, Trigger). In the post-processing stage, we convert them back.

Regarding event division, a natural thought is to directly aggregate all arguments sharing the same event type into one event. But this is not comprehensive enough because a single input might have multiple events of the same type. What if we include trigger words? Still not enough, as multiple events of the same type might share the same trigger word. For example, a sample in DuEE is: "Main members Cheng Jie and Wang Shaowei were sentenced by the court of first instance to 22 years and 20 years of fixed-term imprisonment respectively." This contains two events: "Cheng Jie sentenced to 22 years" and "Wang Shaowei sentenced to 20 years." Both have the trigger "fixed-term imprisonment" and the event type "Imprisonment."

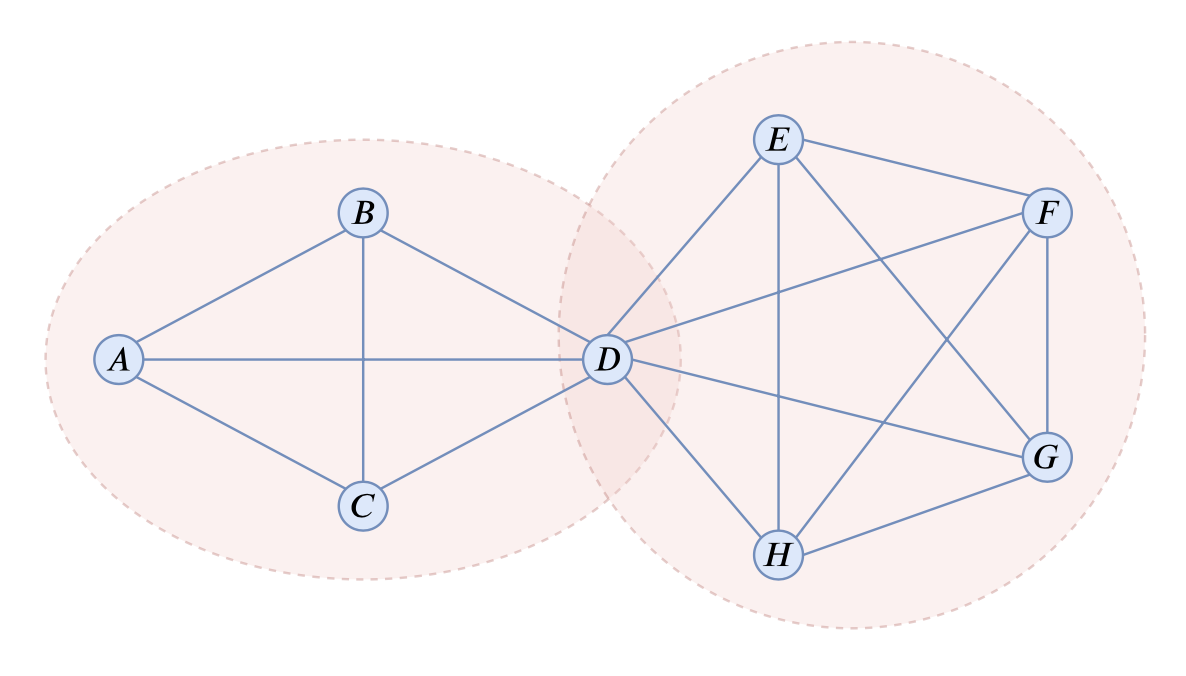

Therefore, we need to design an additional module for event division. We believe that various arguments of the same event are connected. and this connection can be described by an undirected graph. That is, we treat each argument as a node on the graph. Any two argument nodes belonging to the same event can be connected by an edge. If two arguments never appear in the same event, the corresponding nodes are not connected (not adjacent). In this way, any two nodes in the same event are adjacent, which we call a "Complete Graph" or a "Clique." Event division then transforms into searching for complete subgraphs on the graph.

Example of complete subgraphs in a graph

So how do we construct this undirected graph? We follow the approach of TPLinker. If two argument entities are related, their (start, start) and (end, end) positions can be matched. We can use GlobalPointer to predict their matching relationship, just like in the relation extraction GPLinker. Specifically, since we only need to construct an undirected graph, we can mask the lower-triangular part and describe all edges using only the upper-triangular part.

Assuming we have an undirected graph describing argument relationships, how do we search for all complete subgraphs? It looks similar to graph segmentation but is not identical, because in our scenario, nodes can be reused, meaning the same entity can simultaneously be an argument for multiple different events. For example, the 8 nodes in the image above can result in two complete subgraphs, where node $D$ appears in both. This represents that we can partition two events sharing a common argument $D$.

After analysis, I conceived the following recursive search algorithm:

1. Enumerate all node pairs on the graph. If all node pairs are adjacent, then the graph itself is a complete graph; return it directly. If there are non-adjacent node pairs, execute step 2.

2. For each pair of non-adjacent nodes, find the set of all nodes adjacent to each respectively (including the node itself) to form subgraphs, and then perform step 1 on each of these subgraph sets.

Taking the above figure as an example again, we can find that $B$ and $E$ are a pair of non-adjacent nodes. We then find their adjacent sets as $\{A, B, C, D\}$ and $\{D, E, F, G, H\}$, and continue to search for non-adjacent pairs within $\{A, B, C, D\}$ and $\{D, E, F, G, H\}$. Since none are found, both $\{A, B, C, D\}$ and $\{D, E, F, G, H\}$ are complete subgraphs. Note that this does not depend on the order of the non-adjacent pairs, because we must perform the same operation for "all" non-adjacent pairs. For instance, if we found $A$ and $F$ as a non-adjacent pair, we would similarly find their adjacent sets $\{A, B, C, D\}$ and $\{D, E, F, G, H\}$ and execute recursively. Therefore, throughout the process, we might obtain many duplicate results, but we will not miss any, nor will we be affected by the identification order; we just perform deduplication at the end.

Additionally, during each search, we only need to search nodes of the same event type. In most cases, there are only a handful of arguments for the same event type, so although the algorithm looks complex, it actually runs very fast.

The design for GPLinker event extraction is now complete. In summary, we need one nested entity recognition model to identify arguments, and then one "head-head" matching and one "tail-tail" matching model to build the relationships between arguments. These modules are surprisingly consistent with the GPLinker model for relation extraction, and all can be accomplished using GlobalPointer. Therefore, we still name it "GPLinker." The code is unified at:

Github Address: https://github.com/bojone/GPLinker

I conducted simple experiments on DuEE and DuEE-fin and submitted them to the Qianyan Leaderboard. The results are as follows:

\[ \begin{array}{c|ccc} \hline & \text{Precision} & \text{Recall} & \text{F1} \\ \hline \text{DuEE} & 82.65 & 80.31 & 81.47 \\ \hline \text{DuEE-fin} & 50.35 & 65.19 & 56.82 \\ \hline \end{array} \]Looking at these two scores alone, they rank 5th on the leaderboard. It's not particularly outstanding, and there is still some distance to the 1st place. However, this article wasn't specifically written to win the competition, so I didn't perform further optimizations for the competition data. This score can be considered quite respectable. As for not comparing with other event extraction models, it is because I am not very familiar with this field. After briefly looking at a few papers on relation extraction, I felt the models there were exceptionally complex and lacked the interest to replicate them.

Finally, the GlobalPointer used in the code is entirely Efficient GlobalPointer. I also compared it with the standard version of GlobalPointer and found that the standard version converges faster initially but yields poorer final results. This re-confirms the effectiveness of Efficient GlobalPointer.

GPLinker for event extraction pursues simplicity and completeness. In actual practice, it might not be the most effective solution. One obvious problem is its significant reliance on data; its performance might be substandard in few-shot scenarios. This is essentially because GPLinker is sufficiently complete—meaning it has high degrees of freedom (can accommodate enough scenarios)—meaning the model lacks prior information, which increases the learning difficulty.

However, GPLinker indeed has features of being simple and efficient, and theoretically, it does not suffer from the Exposure Bias problem. Therefore, in practice, if GPLinker's performance is lacking, one viable solution is to first use another method that achieves good results (likely high-performance but low-efficiency) to create a model version, and then distill it into GPLinker. This way, one can balance both performance and efficiency.

This article introduced the approach of using GPLinker for event extraction: first using nested entity extraction to extract arguments, and then transforming event partitioning into a complete subgraph search problem. The entire model is relatively concise and complete, and theoretically free from the Exposure Bias problem.