By 苏剑林 | April 20, 2022

As is common knowledge, classification models usually obtain an encoding vector first, then connect it to a Dense layer to predict the probability of each category, and the output during prediction is the category with the highest probability. But have you ever wondered about this possibility: a trained classification model might have "unpredictable categories"? That is, no matter what the input is, it is impossible to predict a certain category $k$; category $k$ can never become the one with the highest probability.

Of course, this situation generally only occurs in scenarios where the number of categories far exceeds the dimension of the encoding vector; conventional classification problems are rarely so extreme. However, we know that a language model is essentially a classification model, and its number of categories—the total size of the vocabulary—often far exceeds the vector dimension. So, does our language model have "unpredictable words"? (Considering only Greedy decoding).

The ACL 2022 paper "Low-Rank Softmax Can Have Unargmaxable Classes in Theory but Rarely in Practice" first explored this question. As the title suggests, the answer is "they exist in theory but the probability of occurrence in practice is very small."

First, let's look at "theoretical existence." To prove its existence, we only need to construct a specific example. Let the vectors for each category be $\boldsymbol{w}_1, \boldsymbol{w}_2, \cdots, \boldsymbol{w}_n \in \mathbb{R}^d$, and the bias terms be $b_1, b_2, \cdots, b_n$. Assuming category $k$ is predictable, then there exists a $\boldsymbol{z} \in \mathbb{R}^d$ that simultaneously satisfies \begin{equation}\langle\boldsymbol{w}_k,\boldsymbol{z}\rangle + b_k > \langle\boldsymbol{w}_i,\boldsymbol{z}\rangle + b_i \quad (\forall i \neq k)\end{equation} Conversely, if category $k$ is unpredictable, then for any $\boldsymbol{z} \in \mathbb{R}^d$, there must exist some $i \neq k$ that satisfies \begin{equation}\langle\boldsymbol{w}_k,\boldsymbol{z}\rangle + b_k \leq \langle\boldsymbol{w}_i,\boldsymbol{z}\rangle + b_i\end{equation} Since we only need to provide an example now, for simplicity, let's first consider the case without bias terms and let $k=n$. In this case, the condition is $\langle \boldsymbol{w}_i - \boldsymbol{w}_n, \boldsymbol{z}\rangle \geq 0$. That is to say, for any vector $\boldsymbol{z}$, one must be able to find a vector $\boldsymbol{w}_i - \boldsymbol{w}_n$ whose angle with it is less than or equal to 90 degrees. It is not hard to imagine that when the number of vectors is greater than the space dimension and the vectors are uniformly distributed in the space, this might occur. For example, any vector in a 2D plane must have an angle of less than 90 degrees with one of $(0,1), (1,0), (0,-1), (-1,0)$. Thus, we can construct an example: \begin{equation}\left\{\begin{aligned} &\boldsymbol{w}_5 = (1, 1) \quad(\boldsymbol{w}_5 \text{ can be chosen arbitrarily})\\ &\boldsymbol{w}_1 = (1, 1) + (0, 1) = (1, 2)\\ &\boldsymbol{w}_2 = (1, 1) + (1, 0) = (2, 1)\\ &\boldsymbol{w}_3 = (1, 1) + (0, -1) = (1, 0)\\ &\boldsymbol{w}_4 = (1, 1) + (-1, 0) = (0, 1)\\ \end{aligned}\right.\end{equation} In this example, category 5 is unpredictable. If you don't believe it, you can try substituting some $\boldsymbol{z}$ values.

Now that we have confirmed that "unpredictable categories" can exist, a natural question is: for a trained model, given $\boldsymbol{w}_1, \boldsymbol{w}_2, \cdots, \boldsymbol{w}_n \in \mathbb{R}^d$ and $b_1, b_2, \cdots, b_n$, how can we determine if there are unpredictable categories among them?

According to the description in the previous section, from the perspective of solving inequalities, if category $k$ is predictable, then the solution set of the following system of inequalities is non-empty: \begin{equation}\langle\boldsymbol{w}_k - \boldsymbol{w}_i, \boldsymbol{z}\rangle + (b_k - b_i) > 0 \quad (\forall i \neq k)\end{equation} Without loss of generality, we also set $k=n$, and denote $\Delta\boldsymbol{w}_i = \boldsymbol{w}_n - \boldsymbol{w}_i$ and $\Delta b_i = b_n - b_i$. Note that: \begin{equation}\langle\Delta\boldsymbol{w}_i, \boldsymbol{z}\rangle + \Delta b_i > 0 \, (i = 1,2,\cdots,n-1) \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad \min_i \langle\Delta\boldsymbol{w}_i, \boldsymbol{z}\rangle + \Delta b_i > 0\end{equation} Therefore, as long as we try to maximize $\min\limits_i \langle\Delta\boldsymbol{w}_i, \boldsymbol{z}\rangle + \Delta b_i$, if the final result is positive, then category $n$ is predictable; otherwise, it is unpredictable. Readers who have read "Chatting about Multi-task Learning (II): Acting on Gradients" will find this problem "familiar." In particular, if there are no bias terms, it is almost identical to the process of finding "Pareto optimality" in multi-task learning.

Now the problem becomes: \begin{equation}\max_{\boldsymbol{z}} \min_i \langle\Delta\boldsymbol{w}_i, \boldsymbol{z}\rangle + \Delta b_i\end{equation} To avoid divergence to infinity, we can add a constraint $\Vert \boldsymbol{z}\Vert \leq r$: \begin{equation}\max_{\Vert \boldsymbol{z}\Vert \leq r} \min_i \langle\Delta\boldsymbol{w}_i, \boldsymbol{z}\rangle + \Delta b_i \end{equation} where $r$ is a constant. As long as $r$ is large enough, it can sufficiently match the actual situation because the output of a neural network is usually bounded. The subsequent process is almost the same as in "Chatting about Multi-task Learning (II): Acting on Gradients". First, we introduce: \begin{equation}\mathbb{P}^{n-1} = \left\{(\alpha_1, \alpha_2, \cdots, \alpha_{n-1}) \left| \alpha_1, \alpha_2, \cdots, \alpha_{n-1} \geq 0, \sum_i \alpha_i = 1 \right.\right\}\end{equation} Then the problem becomes: \begin{equation}\max_{\Vert \boldsymbol{z}\Vert \leq r} \min_{\alpha \in \mathbb{P}^{n-1}} \left\langle \sum_i \alpha_i \Delta\boldsymbol{w}_i, \boldsymbol{z} \right\rangle + \sum_i \alpha_i \Delta b_i\end{equation} According to Von Neumann's Minimax Theorem, the order of $\max$ and $\min$ can be swapped: \begin{equation}\min_{\alpha \in \mathbb{P}^{n-1}} \max_{\Vert \boldsymbol{z}\Vert \leq r} \left\langle \sum_i \alpha_i \Delta\boldsymbol{w}_i, \boldsymbol{z} \right\rangle + \sum_i \alpha_i \Delta b_i\end{equation} Obviously, the $\max$ step is achieved when $\Vert\boldsymbol{z}\Vert=r$ and $\boldsymbol{z}$ is in the same direction as $\sum\limits_i \alpha_i \Delta\boldsymbol{w}_i$. The result is: \begin{equation}\min_{\alpha \in \mathbb{P}^{n-1}} r \left\Vert \sum_i \alpha_i \Delta\boldsymbol{w}_i \right\Vert + \sum_i \alpha_i \Delta b_i\end{equation} When $r$ is large enough, the influence of the bias term becomes very small, so this is almost equivalent to the case without bias terms: \begin{equation}\min_{\alpha \in \mathbb{P}^{n-1}} \left\Vert \sum_i \alpha_i \Delta\boldsymbol{w}_i \right\Vert\end{equation} The final solution process for the $\min$ has already been discussed in "Chatting about Multi-task Learning (II): Acting on Gradients", mainly using the Frank-Wolfe algorithm, which will not be repeated here.

(Note: The above identification process was derived by the author himself and is not the same as the method in the paper "Low-Rank Softmax Can Have Unargmaxable Classes in Theory but Rarely in Practice".)

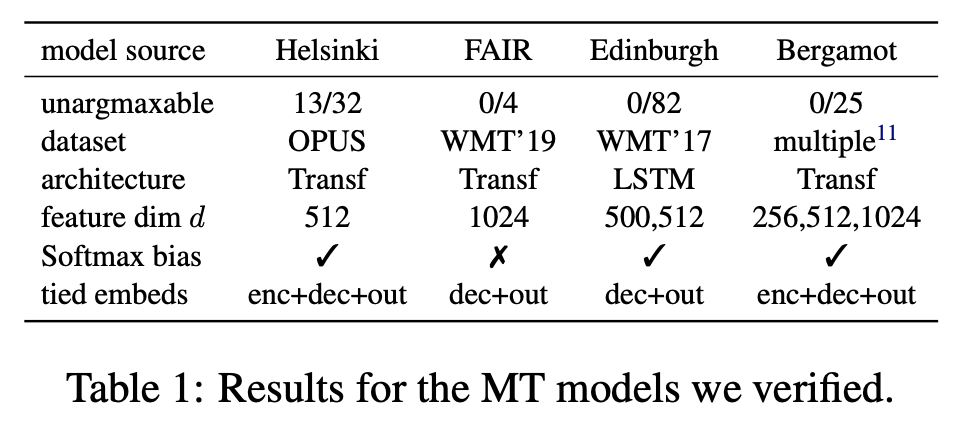

The previous discussions were theoretical. So, how likely is it for actual language models to have "unpredictable words"? The original paper tested some trained language models and generative models and found that the probability of occurrence is actually very small. For example, the test results of machine translation models are shown in the following table:

This is not difficult to understand. From the previous discussion, we know that "unpredictable words" generally only appear when the number of categories is much larger than the vector dimension, which is the "Low-Rank" mentioned in the original paper's title. However, due to the "Curse of Dimensionality," the concept of "much larger" is not as intuitive as we might think. For example, for a 2D space, 4 categories can be called "much larger," but for a 200-dimensional space, even a vocabulary of 40,000 does not count as "much larger." The vector dimensions of common language models are basically in the hundreds, while the vocabulary size is at most in the hundreds of thousands; thus, it still doesn't count as "much larger," so the probability of "unpredictable words" occurring is very small.

In addition, we can prove that if all $\boldsymbol{w}_i$ are distinct but have the same magnitude, "unpredictable words" will absolutely not occur. Therefore, this unpredictable situation only appears when there is a large discrepancy in the magnitudes of $\boldsymbol{w}_i$. In current mainstream deep models, due to the application of various Normalization techniques, situations where the magnitudes of $\boldsymbol{w}_i$ differ significantly are rare, further reducing the probability of "unpredictable words" appearing.

Of course, as stated at the beginning of the article, the "unpredictable words" referred to here pertain to Maximization prediction, i.e., Greedy Search. If Beam Search or random sampling is used, then even if an "unpredictable word" exists, it can still potentially be generated. This "unpredictable word" is more of a fun but not very practical theoretical concept.

This article introduced a phenomenon that has no practical value but is quite interesting: your language model might have some "unpredictable words" that can never become the most probable ones.