By 苏剑林 | June 28, 2022

In the past few days, I came across the paper "Exploring and Exploiting Hubness Priors for High-Quality GAN Latent Sampling" and learned a new term: the "Hubness phenomenon." It refers to an aggregation effect in high-dimensional space, which is essentially one of the manifestations of the "curse of dimensionality." Using the concept of Hubness, the paper derives a scheme to improve the generation quality of GAN models, which seems quite interesting. Therefore, I took the opportunity to learn more about the Hubness phenomenon and recorded my findings here for your reference.

"Curse of dimensionality" is a very broad concept. Any conclusion in high-dimensional space that differs significantly from its 2D or 3D counterparts can be called a "curse of dimensionality." For example, as introduced in "Distribution of the Angle Between Two Random Vectors in n-Dimensional Space," "any two vectors in a high-dimensional space are almost always orthogonal." Many manifestations of the curse of dimensionality share the same source: "The ratio of the volume of an $n$-dimensional unit sphere to its circumscribed hypercube collapses to 0 as the dimension increases." This includes the "Hubness phenomenon" discussed in this article.

In "Masterpieces of Nature: Calculating the Volume of an n-Dimensional Sphere," we derived the volume formula for an $n$-dimensional sphere. From it, we know that the volume of an $n$-dimensional unit sphere is:

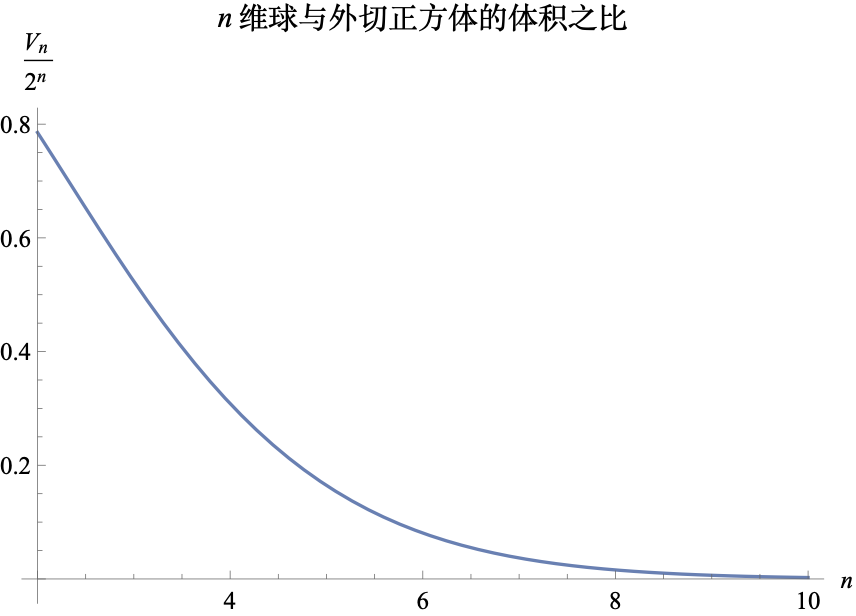

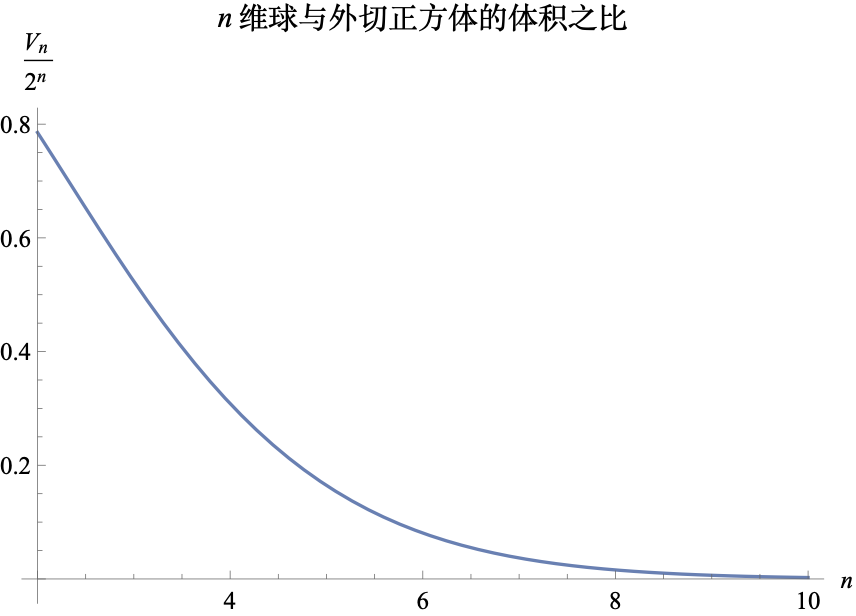

\begin{equation}V_n = \frac{\pi^{n/2}}{\Gamma\left(\frac{n}{2}+1\right)}\end{equation}The side length of the corresponding circumscribed hypercube is $2$, so its volume is naturally $2^n$. Therefore, the ratio of the volumes is $V_n / 2^n$. Its graph is shown below:

As can be seen, as the dimension increases, this ratio quickly tends toward 0. A descriptive way to put this is: "As the dimension increases, the sphere becomes increasingly insignificant." This tells us that if we try to achieve uniform sampling within a sphere using "uniform distribution + rejection sampling," the efficiency in high-dimensional space will be extremely low (the rejection rate will be close to 100%). Another way to understand this is that "most points in a high-dimensional sphere are concentrated near the surface," and the ratio of the region from the center to the surface becomes smaller and smaller.

Now, let's turn to the Hubness phenomenon. It states that when a batch of points is randomly selected in a high-dimensional space, "there are always some points that frequently appear in the $k$-nearest neighbors of other points."

How should we understand this? Suppose we have $N$ points $x_1, x_2, \dots, x_N$. For each $x_i$, we can find the $k$ points closest to it; these $k$ points are called the "$k$-neighbors of $x_i$." With this concept, we can count how many times each point appears in the $k$-neighbors of other points. This count is called the "Hub value." The larger the Hub value, the more likely the point is to appear in the $k$-neighbors of other points.

The Hubness phenomenon states: there are always a few points whose Hub values are significantly large. If Hub values represent "wealth," a vivid metaphor would be "80% of the wealth is concentrated in 20% of the people," and as the dimension increases, this "wealth gap" grows larger. If Hub values represent "connections," it can be compared to "there are always a few people in a community who possess extremely extensive social resources."

How does the Hubness phenomenon arise? It is actually related to the collapse of the $n$-dimensional sphere mentioned in the previous section. We know that the point with the smallest sum of squared distances to all points is exactly the mean point:

\begin{equation}\frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N x_i = c^* = \mathop{\text{argmin}}_c \sum_{i=1}^N \Vert x_i - c\Vert^2\end{equation}This implies that points near the mean vector have smaller average distances to all points and have a better chance of becoming the $k$-neighbors of more points. The collapse of the $n$-dimensional sphere tells us that the "neighborhood near the mean vector"—a spherical neighborhood centered at the mean—occupies a very small proportion of the space. Consequently, we see the phenomenon where "very few points appear in the $k$-neighbors of many points." Of course, using the mean vector here is a more intuitive way to understand it; for general data points, points closer to the center of density will have larger Hub values.

So, what does the GAN generation quality improvement scheme mentioned at the beginning have to do with the Hubness phenomenon? The paper "Exploring and Exploiting Hubness Priors for High-Quality GAN Latent Sampling" proposes a prior hypothesis: the larger the Hub value, the better the generation quality of the corresponding point.

Specifically, the general GAN sampling generation process is $z \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1), x=G(z)$. We can first sample $N$ points $z_1, z_2, \dots, z_N$ from $\mathcal{N}(0,1)$, and then calculate the Hub value of each sample point. The original paper found that the Hub value is positively correlated with generation quality, so they only keep sample points with a Hub value greater than or equal to a threshold $t$ for generation. This is an "ex-ante" screening strategy. The reference code is as follows:

def get_z_samples(size, t=50):

"""Filter sampling results via Hub values"""

Z = np.empty((0, z_dim))

while len(Z) < size:

z = np.random.randn(size, z_dim)

# Calculate Hub values for these sample points; this part is omitted

hub_values = calculate_hub_values(z)

z = z[hub_values >= t]

Z = np.concatenate([Z, z], 0)[:size]

print('%s / %s' % (len(Z), size))

return ZWhy filter by Hub values? Based on the previous discussion, a larger Hub value means a point is closer to the sample center—or more accurately, the density center. This implies there are many surrounding neighbor points, making it unlikely to be an outlier that hasn't been adequately trained. Therefore, the sampling quality is relatively higher. Multiple experimental results in the paper confirm this conclusion.

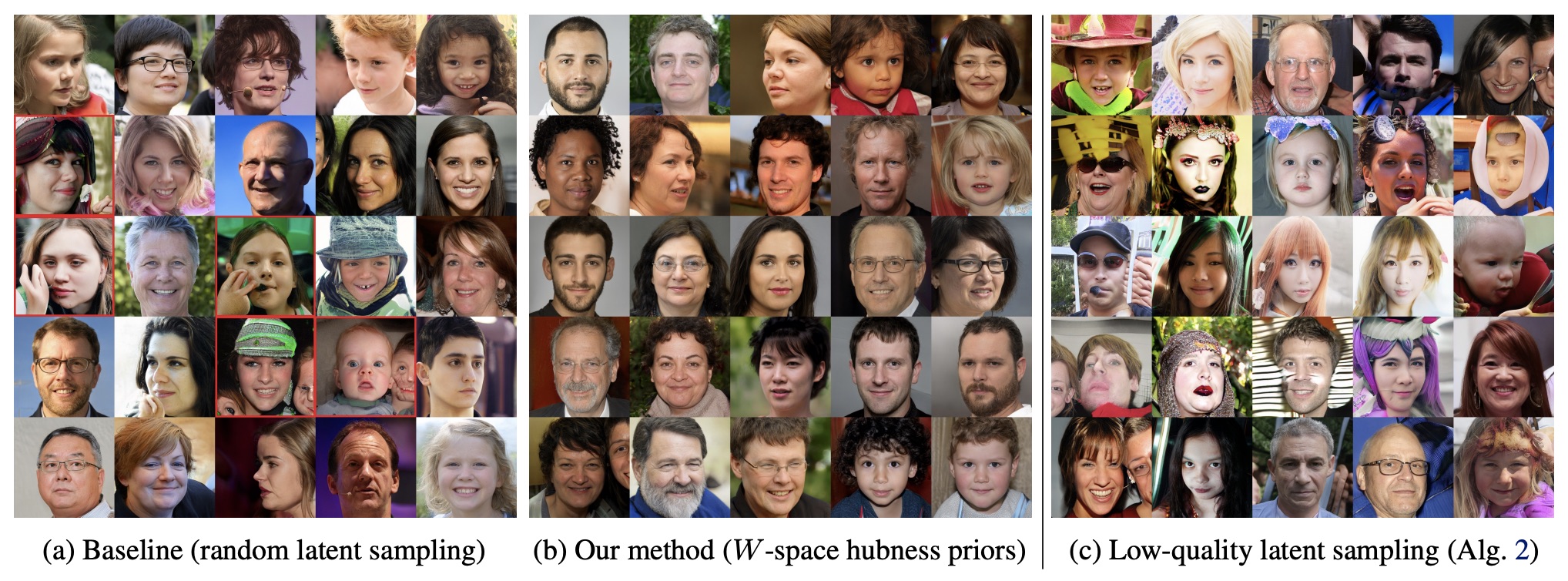

Comparison of generation quality based on Hub value filtering

This article briefly introduced the Hubness phenomenon in the "curse of dimensionality" and described its application in improving the generation quality of GANs.