By 苏剑林 | August 12, 2022

For generative diffusion models, a crucial question is how to choose the variance of the generation process, as different variances significantly impact the generation quality.

In "Diffusion Model Notes (2): DDPM = Autoregressive VAE", we mentioned that DDPM derived two usable results by assuming the data followed two special distributions respectively. In "Diffusion Model Notes (4): DDIM = High-Perspective DDPM", DDIM adjusted the generation process, making the variance a hyperparameter and even allowing for zero-variance generation; however, the generation quality of zero-variance DDIM is generally worse than non-zero variance DDPM. Furthermore, "Diffusion Model Notes (5): SDE Perspective of the General Framework" showed that the variance of the forward and reverse SDEs should be consistent, but this principle theoretically only holds when $\Delta t \to 0$. "Improved Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models" proposed treating it as a trainable parameter to be learned, though this increases training difficulty.

So, how exactly should the variance of the generation process be set? Two papers from this year, "Analytic-DPM: an Analytic Estimate of the Optimal Reverse Variance in Diffusion Probabilistic Models" and "Estimating the Optimal Covariance with Imperfect Mean in Diffusion Probabilistic Models", seem to provide a relatively perfect answer to this question. Next, let's appreciate their results together.

Uncertainty

In fact, these two papers come from the same team, and the authors are essentially the same. The first paper (referred to as Analytic-DPM hereafter) derived an analytical solution for the unconditional variance based on DDIM. The second paper (referred to as Extended-Analytic-DPM) weakened the assumptions of the first paper and proposed an optimization method for conditional variance. This article will first introduce the results of the first paper.

In "Diffusion Model Notes (4): DDIM = High-Perspective DDPM", we derived that for a given $p(\boldsymbol{x}_t|\boldsymbol{x}_0) = \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{x}_t;\bar{\alpha}_t \boldsymbol{x}_0,\bar{\beta}_t^2 \boldsymbol{I})$, the corresponding general solution for $p(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}|\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{x}_0)$ is:

\begin{equation}p(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}|\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{x}_0) = \mathcal{N}\left(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}; \frac{\sqrt{\bar{\beta}_{t-1}^2 - \sigma_t^2}}{\bar{\beta}_t} \boldsymbol{x}_t + \gamma_t \boldsymbol{x}_0, \sigma_t^2 \boldsymbol{I}\right)\end{equation}

where $\gamma_t = \bar{\alpha}_{t-1} - \frac{\bar{\alpha}_t\sqrt{\bar{\beta}_{t-1}^2 - \sigma_t^2}}{\bar{\beta}_t}$, and $\sigma_t$ is the adjustable standard deviation parameter. In DDIM, the subsequent processing workflow is: use $\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)$ to estimate $\boldsymbol{x}_0$, and then assume:

\begin{equation}p(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}|\boldsymbol{x}_t) \approx p(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}|\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{x}_0=\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t))\end{equation}

However, from a Bayesian perspective, this treatment is quite improper because predicting $\boldsymbol{x}_0$ from $\boldsymbol{x}_t$ cannot be perfectly accurate; it carries a certain degree of uncertainty. Therefore, we should use a probability distribution rather than a deterministic function to describe it. In fact, strictly speaking:

\begin{equation}p(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}|\boldsymbol{x}_t) = \int p(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}|\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{x}_0)p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)d\boldsymbol{x}_0\end{equation}

The exact $p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)$ is usually unobtainable, but here we only need a coarse approximation. Thus, we use a normal distribution $\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{x}_0;\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t),\bar{\sigma}_t^2\boldsymbol{I})$ to approach it (how to approach it will be discussed later). With this approximate distribution, we can write:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}

\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} =&\, \frac{\sqrt{\bar{\beta}_{t-1}^2 - \sigma_t^2}}{\bar{\beta}_t}\boldsymbol{x}_t + \gamma_t \boldsymbol{x}_0 + \sigma_t\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_1 \\

\approx&\, \frac{\sqrt{\bar{\beta}_{t-1}^2 - \sigma_t^2}}{\bar{\beta}_t}\boldsymbol{x}_t + \gamma_t \big(\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) + \bar{\sigma}_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_2\big) + \sigma_t\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_1 \\

=&\, \left(\frac{\sqrt{\bar{\beta}_{t-1}^2 - \sigma_t^2}}{\bar{\beta}_t}\boldsymbol{x}_t + \gamma_t \bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)\right) + \underbrace{\big(\sigma_t\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_1 + \gamma_t\bar{\sigma}_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_2\big)}_{\sim \sqrt{\sigma_t^2 + \gamma_t^2\bar{\sigma}_t^2}\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}} \\

\end{aligned}\end{equation}

where $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_1,\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_2,\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}\sim\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0},\boldsymbol{I})$. It can be seen that $p(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}|\boldsymbol{x}_t)$ is closer to a normal distribution with mean $\frac{\sqrt{\bar{\beta}_{t-1}^2 - \sigma_t^2}}{\bar{\beta}_t}\boldsymbol{x}_t + \gamma_t \bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)$ and covariance $\left(\sigma_t^2 + \gamma_t^2\bar{\sigma}_t^2\right)\boldsymbol{I}$. The mean is consistent with previous results; the difference is that the variance has an additional term $\gamma_t^2\bar{\sigma}_t^2$. Therefore, even if $\sigma_t=0$, the corresponding variance is not 0. This additional term is the correction for the optimal variance proposed in the first paper.

Mean Optimization

Now let's discuss how to use $\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{x}_0;\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t),\bar{\sigma}_t^2\boldsymbol{I})$ to approach the true $p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)$, which essentially means finding the mean and covariance of $p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)$.

For the mean $\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)$, it depends on $\boldsymbol{x}_t$, so a model is needed to fit it, and training the model requires a loss function. Utilizing:

\begin{equation}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}}[\boldsymbol{x}] = \mathop{\text{argmin}}_{\boldsymbol{\mu}}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}}\left[\Vert \boldsymbol{x} - \boldsymbol{\mu}\Vert^2\right]\label{eq:mean-opt}\end{equation}

We obtain:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}

\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) =&\, \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)}[\boldsymbol{x}_0] \\[5pt]

=&\, \mathop{\text{argmin}}_{\boldsymbol{\mu}}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[\Vert \boldsymbol{x}_0 - \boldsymbol{\mu}\Vert^2\right] \\

=&\, \mathop{\text{argmin}}_{\boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[\left\Vert \boldsymbol{x}_0 - \boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)\right\Vert^2\right] \\

=&\, \mathop{\text{argmin}}_{\boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim \tilde{p}(\boldsymbol{x}_0)}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t|\boldsymbol{x}_0)}\left[\left\Vert \boldsymbol{x}_0 - \boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)\right\Vert^2\right] \\

\end{aligned}\label{eq:loss-1}\end{equation}

This is the loss function used to train $\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)$. If we introduce parameterization as before:

\begin{equation}\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) = \frac{1}{\bar{\alpha}_t}\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t - \bar{\beta}_t \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)\right)\label{eq:bar-mu}\end{equation}

we can obtain the form of the loss function used in DDPM training: $\left\Vert\boldsymbol{\varepsilon} - \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\bar{\alpha}_t \boldsymbol{x}_0 + \bar{\beta}_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}, t)\right\Vert^2$. The results regarding mean optimization are consistent with previous ones and involve no modifications.

Variance Estimation 1

Similarly, by definition, the covariance matrix should be:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}

\boldsymbol{\Sigma}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)=&\, \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[\left(\boldsymbol{x}_0 - \bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)\right)\left(\boldsymbol{x}_0 - \bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)\right)^{\top}\right] \\

=&\, \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[\left((\boldsymbol{x}_0 - \boldsymbol{\mu}) - (\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) - \boldsymbol{\mu})\right)\left((\boldsymbol{x}_0 - \boldsymbol{\mu}) - (\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) - \boldsymbol{\mu})\right)^{\top}\right] \\

=&\, \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[(\boldsymbol{x}_0 - \boldsymbol{\mu}_0)(\boldsymbol{x}_0 - \boldsymbol{\mu}_0)^{\top}\right] - (\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) - \boldsymbol{\mu}_0)(\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) - \boldsymbol{\mu}_0)^{\top}\\

\end{aligned}\label{eq:var-expand}\end{equation}

where $\boldsymbol{\mu}_0$ can be any constant vector, corresponding to the translation invariance of covariance.

The above estimates the full covariance matrix, but it is not what we want, because currently we want to use $\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{x}_0;\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t),\bar{\sigma}_t^2\boldsymbol{I})$ to approach $p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)$, where the designed covariance matrix is $\bar{\sigma}_t^2\boldsymbol{I}$. It has two characteristics:

1. Independent of $\boldsymbol{x}_t$: To eliminate the dependence on $\boldsymbol{x}_t$, we take the average over all $\boldsymbol{x}_t$, i.e., $\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_t = \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t)}[\boldsymbol{\Sigma}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)]$;

2. A multiple of the identity matrix: This means we only need to consider the diagonal parts and take the average of the diagonal elements, i.e., $\bar{\sigma}_t^2 = \text{Tr}(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_t)/d$, where $d=\dim(\boldsymbol{x})$.

Thus we have:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}

\bar{\sigma}_t^2 =&\, \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[\frac{\Vert\boldsymbol{x}_0 - \boldsymbol{\mu}_0\Vert^2}{d}\right] - \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[\frac{\Vert\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) - \boldsymbol{\mu}_0\Vert^2}{d}\right] \\

=&\, \frac{1}{d}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim \tilde{p}(\boldsymbol{x}_0)}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t|\boldsymbol{x}_0)}\left[\Vert\boldsymbol{x}_0 - \boldsymbol{\mu}_0\Vert^2\right] - \frac{1}{d}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[\Vert\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) - \boldsymbol{\mu}_0\Vert^2\right] \\

=&\, \frac{1}{d}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim \tilde{p}(\boldsymbol{x}_0)}\left[\Vert\boldsymbol{x}_0 - \boldsymbol{\mu}_0\Vert^2\right] - \frac{1}{d}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[\Vert\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) - \boldsymbol{\mu}_0\Vert^2\right] \\

\end{aligned}\label{eq:var-1}\end{equation}

This is an analytical form for $\bar{\sigma}_t^2$ provided by the author. Once $\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)$ is trained, the above equation can be approximately calculated by sampling a batch of $\boldsymbol{x}_0$ and $\boldsymbol{x}_t$.

Specially, if we take $\boldsymbol{\mu}_0=\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim \tilde{p}(\boldsymbol{x}_0)}[\boldsymbol{x}_0]$, then it can be written as:

\begin{equation}\bar{\sigma}_t^2 = \mathbb{V}ar[\boldsymbol{x}_0] - \frac{1}{d}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[\Vert\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) - \boldsymbol{\mu}_0\Vert^2\right]\end{equation}

Here $\mathbb{V}ar[\boldsymbol{x}_0]$ is the pixel-level variance of all training data $\boldsymbol{x}_0$. If every pixel value of $\boldsymbol{x}_0$ is within the range $[a,b]$, then its variance obviously won't exceed $\left(\frac{b-a}{2}\right)^2$, leading to the inequality:

\begin{equation}\bar{\sigma}_t^2 \leq \mathbb{V}ar[\boldsymbol{x}_0] \leq \left(\frac{b-a}{2}\right)^2\end{equation}

Variance Estimation 2

The previous solution was an intuitive one provided by the author. The original Analytic-DPM paper provided a slightly different solution, which the author considers relatively less intuitive. By substituting Eq. $\eqref{eq:bar-mu}$, we can obtain:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}

\boldsymbol{\Sigma}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)=&\, \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[\left(\boldsymbol{x}_0 - \bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)\right)\left(\boldsymbol{x}_0 - \bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)\right)^{\top}\right] \\

=&\, \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[\left(\left(\boldsymbol{x}_0 - \frac{\boldsymbol{x}_t}{\bar{\alpha}_t}\right) + \frac{\bar{\beta}_t}{\bar{\alpha}_t} \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)\right)\left(\left(\boldsymbol{x}_0 - \frac{\boldsymbol{x}_t}{\bar{\alpha}_t}\right) + \frac{\bar{\beta}_t}{\bar{\alpha}_t} \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)\right)^{\top}\right] \\

=&\, \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[\left(\boldsymbol{x}_0 - \frac{\boldsymbol{x}_t}{\bar{\alpha}_t}\right)\left(\boldsymbol{x}_0 - \frac{\boldsymbol{x}_t}{\bar{\alpha}_t}\right)^{\top}\right] - \frac{\bar{\beta}_t^2}{\bar{\alpha}_t^2} \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)^{\top}\\

=&\, \frac{1}{\bar{\alpha}_t^2}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t - \bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0\right)\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t - \bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0\right)^{\top}\right] - \frac{\bar{\beta}_t^2}{\bar{\alpha}_t^2} \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)^{\top}\\

\end{aligned}\end{equation}

At this point, if we average both sides over $\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t)$, we have:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}

&\,\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_0|\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t - \bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0\right)\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t - \bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0\right)^{\top}\right] \\

=&\, \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim \tilde{p}(\boldsymbol{x}_0)}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t|\boldsymbol{x}_0)}\left[\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t - \bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0\right)\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t - \bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0\right)^{\top}\right]

\end{aligned}\end{equation}

Don't forget $p(\boldsymbol{x}_t|\boldsymbol{x}_0) = \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{x}_t;\bar{\alpha}_t \boldsymbol{x}_0,\bar{\beta}_t^2 \boldsymbol{I})$, so $\bar{\alpha}_t \boldsymbol{x}_0$ is actually the mean of $p(\boldsymbol{x}_t|\boldsymbol{x}_0)$. Then $\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t|\boldsymbol{x}_0)}\left[\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t - \bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0\right)\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t - \bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0\right)^{\top}\right]$ is actually calculating the covariance matrix of $p(\boldsymbol{x}_t|\boldsymbol{x}_0)$, which is obviously $\bar{\beta}_t^2 \boldsymbol{I}$. Therefore:

\begin{equation}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim \tilde{p}(\boldsymbol{x}_0)}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t|\boldsymbol{x}_0)}\left[\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t - \bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0\right)\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t - \bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0\right)^{\top}\right] = \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_0\sim \tilde{p}(\boldsymbol{x}_0)}\left[\bar{\beta}_t^2 \boldsymbol{I}\right] = \bar{\beta}_t^2 \boldsymbol{I}

\end{equation}

Then:

\begin{equation}

\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_t = \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t)}[\boldsymbol{\Sigma}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)] = \frac{\bar{\beta}_t^2}{\bar{\alpha}_t^2}\left(\boldsymbol{I} - \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[ \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)^{\top}\right]\right)\end{equation}

Taking the trace and dividing by $d$, we get:

\begin{equation}\bar{\sigma}_t^2 = \frac{\bar{\beta}_t^2}{\bar{\alpha}_t^2}\left(1 - \frac{1}{d}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{x}_t\sim p(\boldsymbol{x}_t)}\left[ \Vert\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)\Vert^2\right]\right)\leq \frac{\bar{\beta}_t^2}{\bar{\alpha}_t^2}\label{eq:var-2}\end{equation}

This gives another estimate and upper bound, which is the original result of Analytic-DPM.

Experimental Results

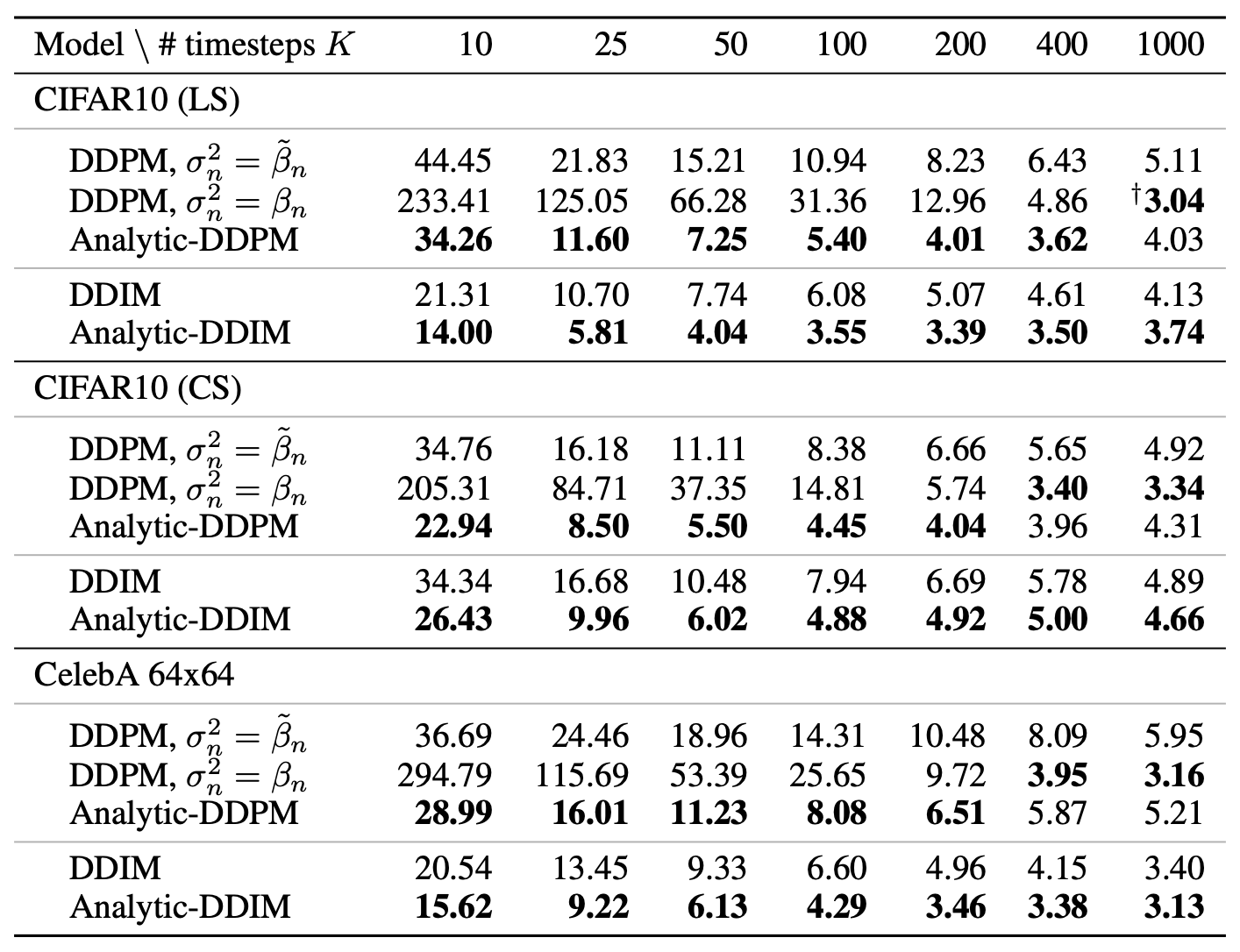

Experimental results from the original paper show that the variance correction made by Analytic-DPM provides a more significant improvement when the number of generation diffusion steps is small. Thus, it is quite meaningful for accelerating diffusion models:

I also tried the Analytic-DPM correction on my previously implemented code. The reference code is at:

Github: https://github.com/bojone/Keras-DDPM/blob/main/adpm.py

When the number of diffusion steps is 10, the comparison between DDPM and Analytic-DDPM is as follows:

It can be seen that when the number of diffusion steps is small, DDPM's generated results are smoother, giving a sort of "heavy skin smoothing" feeling. In contrast, Analytic-DDPM's results appear more realistic but also bring additional noise. In terms of evaluation metrics, Analytic-DDPM is better.

Nitpicking

At this point, we have completed the introduction to Analytic-DPM. The derivation involves some technicality but isn't overly complex; at least the logic is quite clear. If readers find it difficult to understand, they might want to look at the original paper's derivation in the appendix, which takes 7 pages and 13 lemmas. I'm sure after seeing that, the derivation in this article will feel quite friendly, haha.

Admittedly, I admire the authors' insight in being the first to obtain this analytical solution for variance. However, from a "hindsight" perspective, Analytic-DPM made some "detours" in its derivation and results, being "too convoluted" and "too coincidental," and thus lacking heuristic value. One of the most prominent features is that the original paper's results are all expressed using $\nabla_{\boldsymbol{x}_t}\log p(\boldsymbol{x}_t)$, which brings three problems: first, it makes the derivation process particularly un-intuitive, making it hard to understand "how they thought of it"; second, it requires readers to have extra knowledge of score matching results, increasing the difficulty of understanding; finally, in practice, $\nabla_{\boldsymbol{x}_t}\log p(\boldsymbol{x}_t)$ must be expressed back using $\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)$ or $\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)$, which just adds an extra loop.

The starting point of the derivation in this article is that we are estimating parameters of a normal distribution. For a normal distribution, moment estimation is identical to maximum likelihood estimation, so we can directly estimate the corresponding mean and variance. In terms of results, there's no need to force the form to align with $\nabla_{\boldsymbol{x}_t}\log p(\boldsymbol{x}_t)$ or score matching. Obviously, the baseline model for Analytic-DPM is DDIM, and DDIM itself did not start from score matching. Adding links to score matching doesn't benefit the theory or the experiments. Directly aligning with $\bar{\boldsymbol{\mu}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)$ or $\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)$ is more intuitive in form and makes it easier to convert into experimental formats.

Summary

This article shared the optimal diffusion variance estimation results from the Analytic-DPM paper. it provides a directly usable analytical formula for optimal variance estimation, allowing us to improve generation quality without retraining. I simplified the derivation from the original paper with my own logic and performed simple experimental verification.