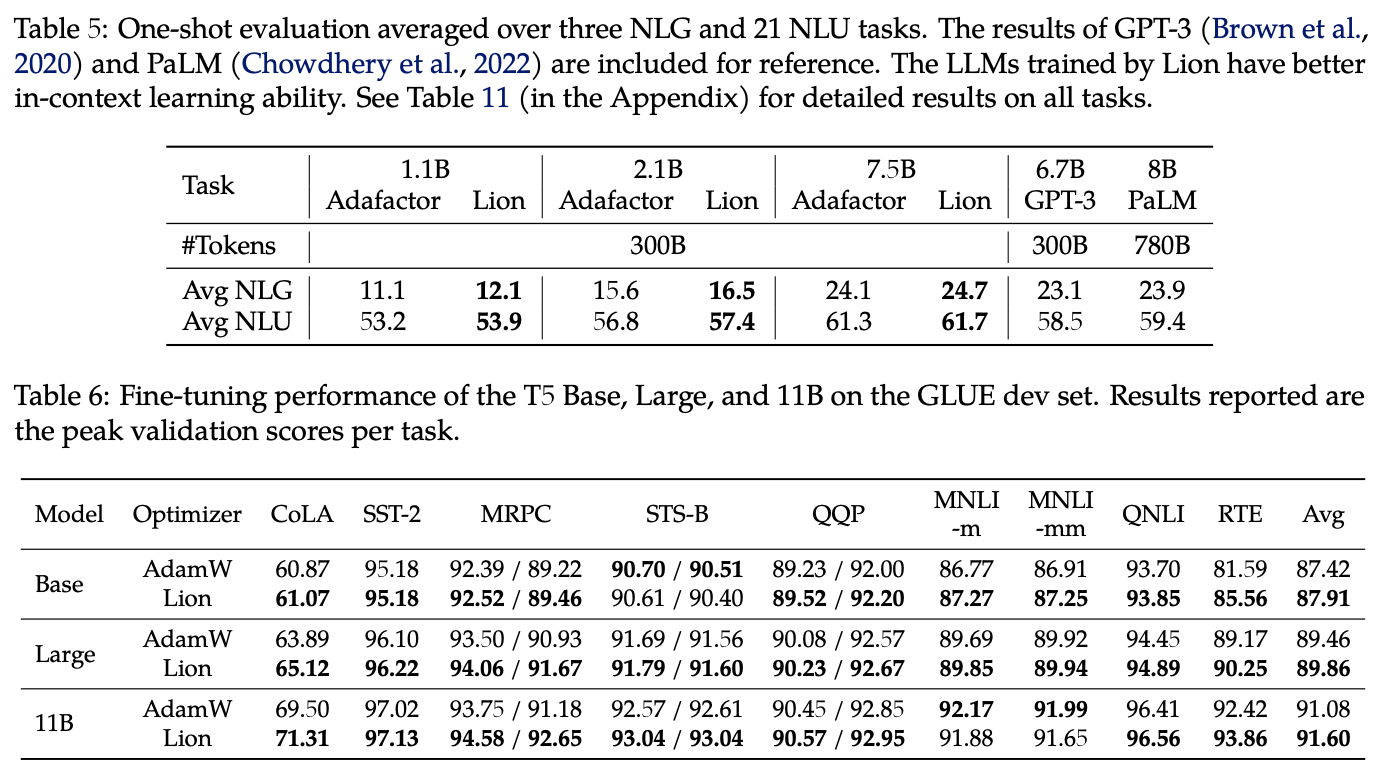

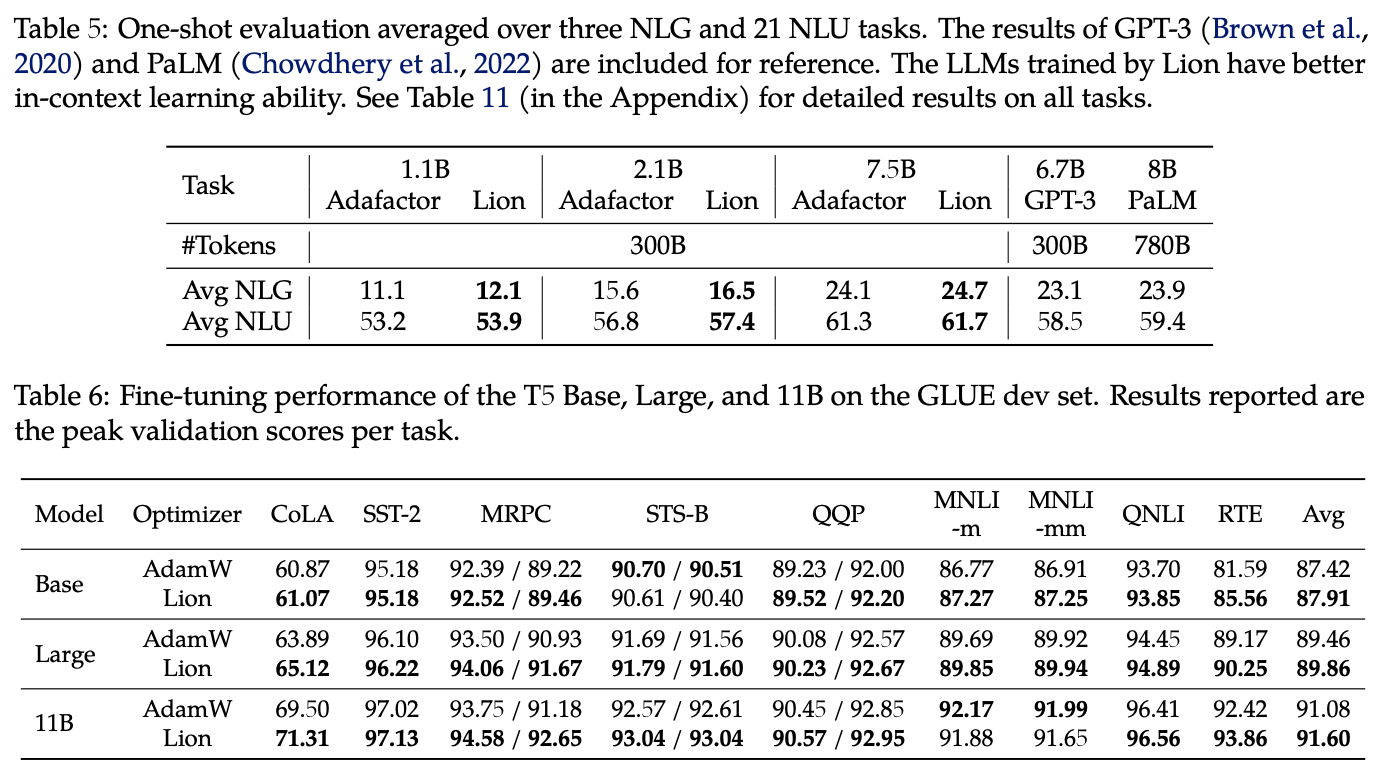

Lion's results on NLU and NLG tasks, most of which are superior to AdamW and Adafactor.

By 苏剑林 | February 16, 2023

Yesterday, I discovered a new paper from Google on arXiv titled "Symbolic Discovery of Optimization Algorithms". It focuses on the automatic search for optimization algorithms. At first glance, it didn't seem particularly interesting, as there have been many similar works, and most of their results are somewhat uninspiring. However, a closer look revealed something Remarkable. The authors used thousands of TPU hours of compute combined with human intervention to discover a faster and more memory-efficient optimizer called Lion (EvoLved Sign Momentum—I have to admit, the backronym is a bit forced). They conducted extensive experiments on various tasks, including image classification, image-text matching, diffusion models, and language model pre-training and fine-tuning. In most tasks, Lion demonstrated better performance than the currently mainstream AdamW and other optimizers.

Saving VRAM while achieving better results—truly having one's cake and eating it too. What kind of optimizer can possess such powerful performance? Let's take a look at the results of this paper.

This article primarily focuses on the discovered optimizer itself, so we will not discuss the details of the search process. Interested readers can refer to the original paper. The update process for the Lion optimizer is as follows:

\begin{equation} \text{Lion}:=\left\{\begin{aligned} &\boldsymbol{u}_t = \text{sign}\big(\beta_1 \boldsymbol{m}_{t-1} + \left(1 - \beta_1\right) \boldsymbol{g}_t\big) \\ &\boldsymbol{\theta}_t = \boldsymbol{\theta}_{t-1} - \eta_t (\boldsymbol{u}_t \color{skyblue}{ + \lambda_t \boldsymbol{\theta}_{t-1}}) \\ &\boldsymbol{m}_t = \beta_2 \boldsymbol{m}_{t-1} + \left(1 - \beta_2\right) \boldsymbol{g}_t \end{aligned}\right. \end{equation}where $\boldsymbol{g}_t = \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} L(\boldsymbol{\theta}_{t-1})$ is the gradient of the loss function, and $\text{sign}$ is the sign function, which converts positive numbers to 1 and negative numbers to -1. We can compare this with the update process of the current mainstream optimizer AdamW:

\begin{equation} \text{Adam}\color{skyblue}{\text{W}}:=\left\{\begin{aligned} &\boldsymbol{m}_t = \beta_1 \boldsymbol{m}_{t-1} + \left(1 - \beta_1\right) \boldsymbol{g}_t\\ &\boldsymbol{v}_t = \beta_2 \boldsymbol{v}_{t-1} + \left(1 - \beta_2\right) \boldsymbol{g}_t^2\\ &\hat{\boldsymbol{m}}_t = \boldsymbol{m}_t\left/\left(1 - \beta_1^t\right)\right.\\ &\hat{\boldsymbol{v}}_t = \boldsymbol{v}_t\left/\left(1 - \beta_2^t\right)\right.\\ &\boldsymbol{u}_t =\hat{\boldsymbol{m}}_t\left/\left(\sqrt{\hat{\boldsymbol{v}}_t} + \epsilon\right)\right.\\ &\boldsymbol{\theta}_t = \boldsymbol{\theta}_{t-1} - \eta_t (\boldsymbol{u}_t \color{skyblue}{ + \lambda_t \boldsymbol{\theta}_{t-1}}) \end{aligned}\right. \end{equation}The contrast is quite obvious. Compared to AdamW, Lion has fewer parameters (missing $\epsilon$), caches one fewer set of parameters $\boldsymbol{v}$ (making it more VRAM-efficient), and removes the division and square root operations, which are the most computationally intensive parts of the AdamW update (making it faster).

Prior to this, the optimizer most similar to Lion was likely SIGNUM, whose update process is:

\begin{equation} \text{SIGNUM}:=\left\{\begin{aligned} &\boldsymbol{m}_t = \beta \boldsymbol{m}_{t-1} + \left(1 - \beta\right) \boldsymbol{g}_t \\ &\boldsymbol{u}_t = \text{sign}\big(\boldsymbol{m}_t\big) \\ &\boldsymbol{\theta}_t = \boldsymbol{\theta}_{t-1} - \eta_t \boldsymbol{u}_t \end{aligned}\right. \end{equation}Like Lion, SIGNUM also uses the sign function to process the update amount and is even more simplified than Lion (equivalent to a special case of Lion where $\beta_1=\beta_2$ and $\lambda_t=0$). Unfortunately, SIGNUM did not achieve better results; its original intent was simply to reduce transmission costs in distributed computing. Lion's update rule is different, especially in that the update of momentum occurs after the update of the parameters, and it has demonstrated its performance advantages in extensive experiments.

As mentioned at the beginning, Lion has been tested on a wide range of tasks. There are many experimental results; below, I list some key findings I consider important.

Lion's results on NLU and NLG tasks, most of which are superior to AdamW and Adafactor.

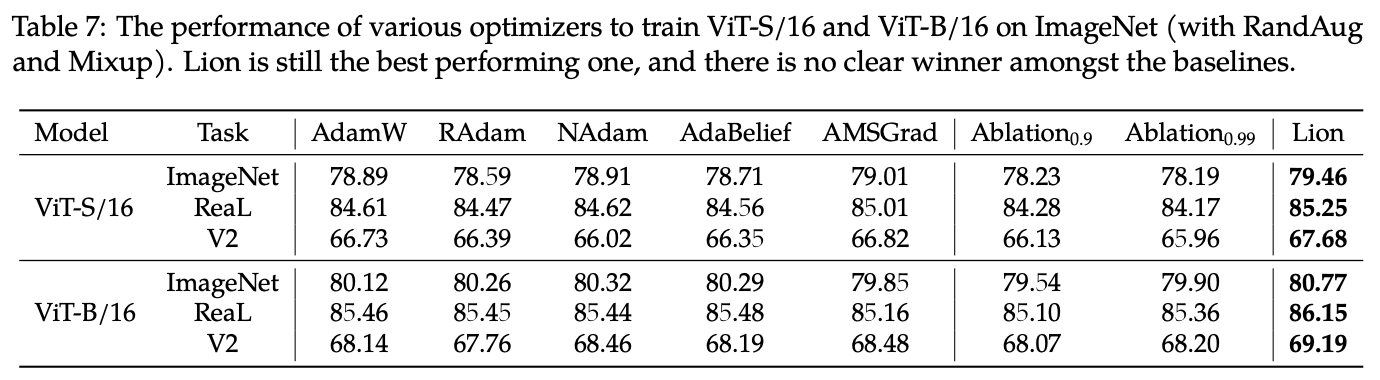

Comparison of Lion with numerous other optimizers on Vision Transformers.

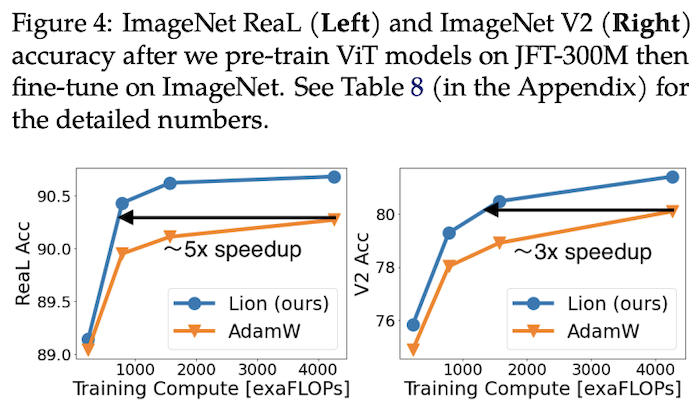

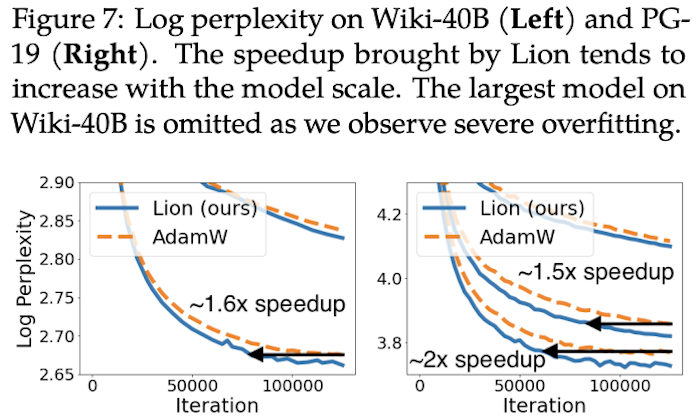

Lion converges faster on CV classification tasks.

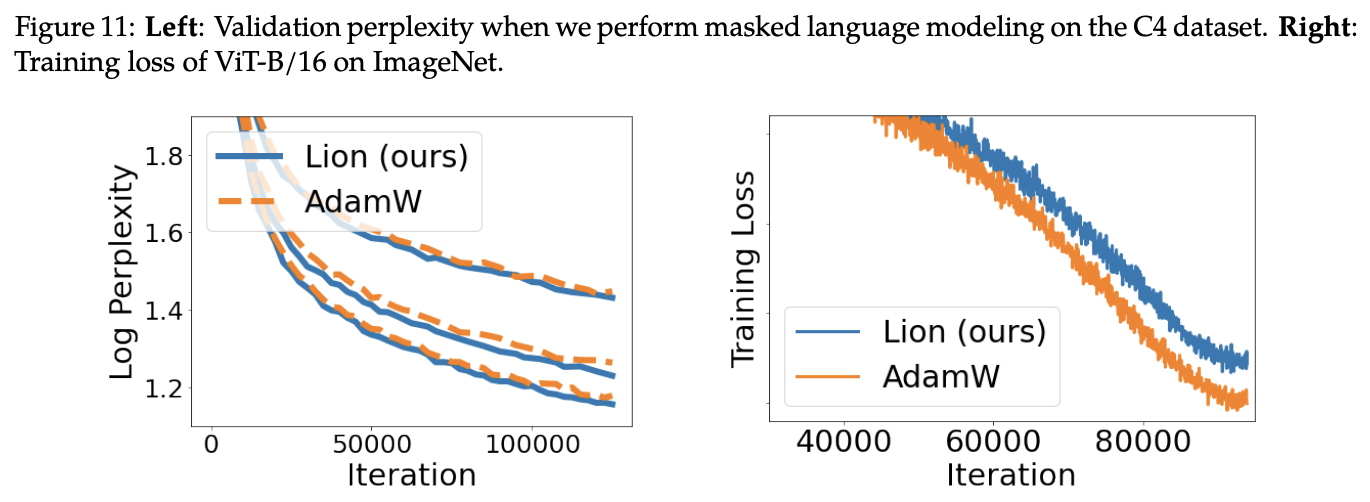

Lion converges faster on NLP autoregressive generation.

The top-right figure shows training curves on ImageNet, indicating that while Lion achieves better validation set performance, its performance on the training set is not necessarily superior to AdamW.

Seeing such impressive results in the paper, I was eager to try it myself. Before running experiments, it's naturally necessary to understand the settings for each hyperparameter. First are $\beta_1, \beta_2$. The result automatically discovered in the original paper was $\beta_1=0.9, \beta_2=0.99$, and this combination was reused in most experiments. However, on NLP tasks, the combination $\beta_1=0.95, \beta_2=0.98$ was used (detailed experimental configurations are in Table 12 on the last page of the paper).

The crucial hyperparameters are the learning rate $\eta$ and weight decay rate $\lambda$. Since the absolute value of each component of Lion's update amount $\boldsymbol{u}$ is 1, which is generally larger than that of AdamW, the learning rate must be reduced by more than 10 times to obtain a similar update magnitude. Consequently, since the learning rate is lowered, the weight decay rate should be increased proportionally to keep the magnitude of weight decay unchanged. The last page of the original paper provides reference values for hyperparameters for various experiments, where the Base-level small models use $\eta = 3\times 10^{-4}$ and $\lambda=0.01$, while large models (over 1 billion parameters) appropriately reduced the learning rate to $\eta = 2\times 10^{-4}$ or even $\eta = 10^{-4}$.

In fact, we previously derived a combination scheme for the learning rate and weight decay rate in "Some 'Alchemy Strategies' Derived from the Ideas of the Amos Optimizer". Referencing that scheme is the most convenient way to set these. In that scheme, the update amount is written as (the notation is slightly different from the previous description but not to the point of confusion):

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{\theta}_{t+1} = \boldsymbol{\theta}_t - (\alpha_t \boldsymbol{u}_t + \rho_t\boldsymbol{\theta}_t)\end{equation}where

\begin{equation}\alpha_t \approx \frac{\alpha_0\Vert\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_0\Vert}{\Vert\boldsymbol{u}_t\Vert} \frac{1}{\kappa t + 1},\quad \rho_t \approx \frac{\alpha_0^2}{2q} \frac{1}{\kappa t + 1}\end{equation}where $\boldsymbol{u}_t$ is the original update amount; $\alpha_0$ is the relative change in parameters (at the initial stage), generally on the order of $10^{-3}$, representing that the change in parameter norm after each step is roughly one-thousandth; $q$ is a hyperparameter that can be set to 1 if there are no special circumstances; $\kappa$ is a hyperparameter controlling the learning rate decay speed, which can be set based on the size of the training data.

Since $\boldsymbol{u}_t$ has undergone the $\text{sign}$ operation, $\Vert\boldsymbol{u}_t\Vert=\sqrt{k}$, where $k$ is the parameter dimension. $\Vert\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_0\Vert\approx\sqrt{k}\sigma$, as we derived in "Some 'Alchemy Strategies' Derived from the Ideas of the Amos Optimizer", where $\sigma$ is the scale of parameter variation. For multiplicative matrices, $\sigma^2$ is its initialization variance. Therefore, after a series of simplifications, we have:

\begin{equation}\alpha_t \approx \frac{\alpha_0\sigma}{\kappa t + 1},\quad \rho_t \approx \frac{\alpha_0^2}{2(\kappa t + 1)}\end{equation}Here, $\alpha_t$ is the $\eta_t$ from before, and $\lambda_t = \rho_t / \alpha_t = \alpha_0 / 2\sigma$. Calculated based on BERT base's $d=768$, the order of magnitude for initialization variance is roughly $1/d$, so $\sigma = \sqrt{1/d}\approx 0.036$. Assuming $\alpha_0$ is $1.11 \times 10^{-3}$ (to round the result), according to the above formula, the learning rate is approximately $4\times 10^{-5}$ and the decay rate is approximately $0.015$. In my own MLM pre-training experiments, this combination performed well.

Personal Implementation: https://github.com/bojone/bert4keras

Overall, Lion's performance is commendable. Whether in the original paper or my own experiments, it holds its own against AdamW. Combined with Lion's speed and VRAM-saving characteristics, it's foreseeable that it will have a place among future mainstream optimizers.

Since the introduction of Adam, its fast convergence has made it the default optimizer for many models. Some scholars have even suggested that this phenomenon in turn leads to an evolutionary effect: all model improvements are drifting in a direction favorable to Adam. In other words, because we chose Adam as the optimizer, we may have discarded many changes that were actually effective but ineffective on the Adam optimizer, leaving only those favorable to Adam. A detailed evaluation can be found in "NEURAL NETWORKS (MAYBE) EVOLVED TO MAKE ADAM THE BEST OPTIMIZER". Therefore, in this context, discovering an optimizer that is simpler and more effective than Adam is a remarkable achievement, even if it was discovered with the help of massive computing power.

Readers might wonder: why can Lion achieve better generalization performance? The original paper's explanation is that the $\text{sign}$ operation introduces additional noise (compared to exact floating-point values), which causes the model to enter a flatter (though not necessarily lower) region of the loss landscape, thereby improving generalization performance. To verify this, the authors compared the anti-interference ability of model weights trained by AdamW and Lion, and the results showed that Lion had better anti-interference ability. Theoretically, however, this only proves that Lion indeed enters a flatter region, but it cannot prove that this result is caused by the $\text{sign}$ operation. Nevertheless, Adam has been published for many years and its mechanism is still not fully understood, while Lion was just recently proposed, so there's no need to be overly pedantic.

My guess is that by using the $\text{sign}$ operation, Lion treats every component equally, allowing the model to fully utilize the role of every component, thus resulting in better generalization. In SGD, the update magnitude is proportional to its gradient; however, the small gradient of some components might just be because they weren't initialized well, not because they are unimportant. Thus, Lion's $\text{sign}$ operation can be seen as providing an opportunity for every parameter to "restore vitality" or even "achieve new glory." In fact, it can be proven that Adam's early update amounts are also close to $\text{sign}$, only gradually deviating as the number of training steps increases.

Is Lion perfect? Obviously not. For instance, the original paper notes that its performance is inferior to AdamW when the batch size is small (less than 64). This is also understandable; $\text{sign}$ already introduces noise, and a small batch size further increases it. Noise is something that must be moderate; when both are superimposed, it is likely that excessive noise leads to performance degradation. Furthermore, because $\text{sign}$ exacerbates noise in the optimization process, divergence (increasing loss) can occur when parameters are improperly set. In such cases, one can try introducing Warmup or increasing the number of Warmup steps. Additionally, Lion still needs to cache momentum parameters, so its VRAM usage is higher than AdaFactor. Whether this part of the parameter overhead can be further optimized remains unknown for now.

This article introduced Google's newly proposed Lion optimizer, which was derived through massive compute and human intervention. Compared to the mainstream AdamW, it is faster and saves memory. Extensive experimental results show that it performs no worse than—and often better than—AdamW in most tasks.