attention, please!

By 苏剑林 | July 27, 2019

Nowadays, in the field of NLP, Attention is all the rage. Of course, it's not just NLP; Attention also holds a place in the CV field (Non-local, SAGAN, etc.). In the early 2018 article "A Brief Reading of 'Attention is All You Need' (Introduction + Code)", we discussed the Attention mechanism. The core of Attention lies in the interaction and fusion of three vector sequences: $\boldsymbol{Q}, \boldsymbol{K}, \boldsymbol{V}$. The interaction between $\boldsymbol{Q}$ and $\boldsymbol{K}$ provides a certain degree of correlation (weight) between pairs of vectors, and the final output sequence is obtained by summing $\boldsymbol{V}$ according to these weights.

Clearly, numerous achievements in NLP & CV have fully affirmed the effectiveness of Attention. In this article, we will introduce some variants of Attention. The common characteristic of these variants is that they are "born for efficiency"—saving both time and video memory.

"Attention is All You Need" discusses what we call "multiplicative Attention," which is currently the most widely used type of Attention:

\begin{equation}Attention(\boldsymbol{Q},\boldsymbol{K},\boldsymbol{V}) = softmax\left(\frac{\boldsymbol{Q}\boldsymbol{K}^{\top}}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)\boldsymbol{V}\end{equation}There is also additive Attention, but additive Attention is not easily implemented in parallel (or consumes more video memory when implemented), so it is generally only used to encode variable-length vector sequences into fixed-length vectors (replacing simple Pooling) and is rarely used for sequence-to-sequence encoding. Among multiplicative Attention, the most widely used is Self Attention. In this case, $\boldsymbol{Q}, \boldsymbol{K}, \boldsymbol{V}$ are all results of the same $\boldsymbol{X}$ after linear transformations. In this way, the output result is a vector sequence of the same length as $\boldsymbol{X}$, and it can directly capture the association between any two vectors in $\boldsymbol{X}$, and is easy to parallelize. These are all advantages of Self Attention.

However, theoretically speaking, the computation time and video memory usage of Self Attention are both at the $\mathcal{O}(n^2)$ level ($n$ is the sequence length). This means that if the sequence length doubles, the video memory usage and calculation time both become 4 times larger. Of course, assuming there are enough parallel cores, the calculation time might not necessarily increase to 4 times, but the fourfold increase in video memory is real and unavoidable. This is also the reason why OOM (Out of Memory) errors frequently occur when fine-tuning BERT.

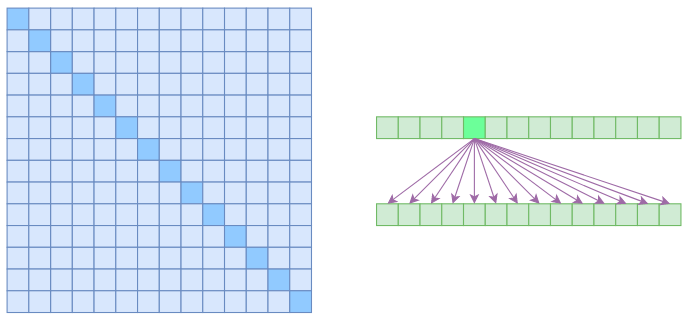

We say Self Attention is $\mathcal{O}(n^2)$ because it needs to calculate the correlation between any two vectors in the sequence, resulting in a correlation matrix of size $n^2$:

Attention matrix of standard Self Attention (left) and association illustration (right)

In the figure above, the left side shows the attention matrix, and the right side shows the associations. This indicates that every element is associated with all elements in the sequence. Therefore, if we want to save video memory and speed up computation, a basic idea is to reduce the calculation of associations—that is, to assume that each element is only related to a part of the elements in the sequence. This is the basic principle of Sparse Attention. The Sparse Attention introduced in this article originates from OpenAI's paper "Generating Long Sequences with Sparse Transformers", but it is not introduced according to the original paper's style, but rather in a way that I consider more natural.

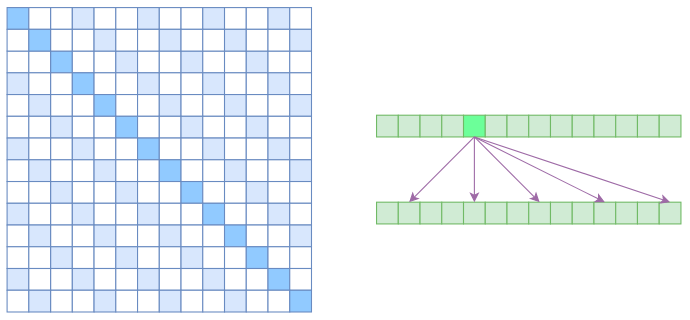

The first concept to introduce is Atrous Self Attention, which can be translated as "dilated self-attention," "hollow self-attention," or "self-attention with holes." Like the subsequent Local Self Attention, these names are coined by me based on their characteristics. The original paper "Generating Long Sequences with Sparse Transformers" does not use these specific terms, but I believe it is meaningful to introduce them separately.

Obviously, Atrous Self Attention is inspired by "Atrous Convolution." As shown in the right figure below, it constrains the correlations, forcing each element to only associate with elements at relative distances of $k, 2k, 3k, \dots$, where $k > 1$ is a pre-set hyperparameter. Looking at the attention matrix on the left, it simply requires that the attention for relative distances that are not multiples of $k$ be set to 0 (white represents 0):

Attention matrix of Atrous Self Attention (left) and association illustration (right)

Since attention is now calculated by "skipping," each element effectively only calculates correlation with approximately $n/k$ elements. Thus, in an ideal case, the operational efficiency and video memory usage become $\mathcal{O}(n^2/k)$, meaning they can be directly reduced to $1/k$ of the original.

Another transitional concept to introduce is Local Self Attention. Usually, the self-attention mechanism is referred to as "Non-local" in the CV field, and obviously, Local Self Attention abandons global associations to re-introduce local associations. Specifically, it is also very simple: it constrains each element to associate only with the $k$ elements before and after it, as well as itself, as shown below:

Attention matrix of Local Self Attention (left) and association illustration (right)

From the attention matrix perspective, attention for relative distances exceeding $k$ is directly set to 0.

In fact, Local Self Attention is very similar to ordinary convolution. Both maintain a window of size $2k+1$ and perform some operations within it. The difference is that ordinary convolution flattens the window and passes it through a fully connected layer to get the output, while here, the output is obtained by weighted averaging within the window via attention. For Local Self Attention, each element only calculates correlation with $2k+1$ elements. Thus, in an ideal case, the operational efficiency and video memory usage become $\mathcal{O}((2k+1)n) \sim \mathcal{O}(kn)$, meaning they grow linearly with $n$. This is a very ideal property—though it directly sacrifices long-range associations.

At this point, we can naturally introduce OpenAI's Sparse Self Attention. We notice that Atrous Self Attention has some "holes," and Local Self Attention fortunately fills these holes. Therefore, a simple way is to use Local Self Attention and Atrous Self Attention alternately. By accumulating both, global associations can theoretically be learned while saving video memory.

(A simple sketch reveals that if the first layer uses Local Self Attention, each output vector fuses several local input vectors. If the second layer then uses Atrous Self Attention, even though it skips elements, because the first layer's output already fused local input vectors, the second layer's output can theoretically be associated with any input vector. That is to say, long-range association is achieved.)

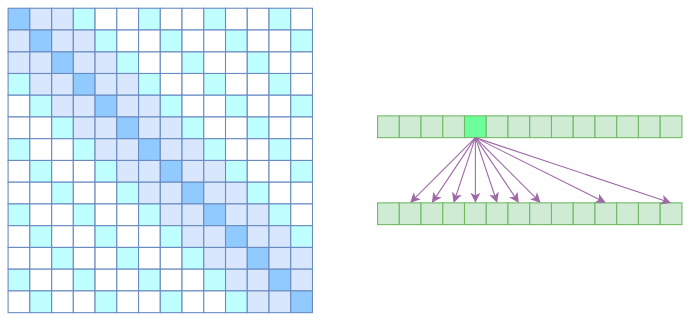

However, OpenAI did not do it this way. It directly merged two types—Atrous Self Attention and Local Self Attention—into one, as shown below:

Attention matrix of Sparse Self Attention (left) and association illustration (right)

It's easy to understand from the attention matrix: attention is set to 0 except for relative distances not exceeding $k$, and relative distances that are $k, 2k, 3k, \dots$. This gives the Attention the characteristic of being "locally dense and remotely sparse," which might be a good prior for many tasks, as tasks truly requiring dense long-range associations are actually quite rare.

The Atrous Self Attention, Local Self Attention, and Sparse Self Attention mentioned above are all considered types of Sparse Attention. Visually, the attention matrices become very sparse. So how do we implement them? If we simply mask the zero parts in the attention matrix, it is mathematically (functionally) sound, but it won't speed up the calculation or save video memory.

OpenAI has open-sourced its own implementation, located at: https://github.com/openai/sparse_attention

This is based on TensorFlow and uses their own sparse matrix library, blocksparse. However, it seems to be encapsulated strangely; I don't know how to migrate it to Keras, and it uses many Python 3 features, so it cannot be used directly in Python 2. Friends using Python 3 and pure TensorFlow can give it a try.

Another issue is that OpenAI's original paper mainly uses Sparse Attention to generate ultra-long sequences, so in both the paper and the code, they masked all upper triangular parts of the attention matrix (to avoid using future information). However, not all scenarios using Sparse Attention are generative, and for an introduction to basic concepts, this is unnecessary. This is one of the reasons why I did not introduce it following the original paper's logic.

For Keras, I have implemented these three types of Sparse Attention based on my own logic and standardized them with the Attention code I wrote previously. It is still placed in the same location:

https://github.com/bojone/attention/blob/master/attention_keras.py

Based on experiments, I found that in my implementation, these three types of Sparse Attention do indeed save some memory compared to full Attention. Unfortunately, except for Atrous Self Attention, the implementations of the other two cannot speed up the process—instead, they slow down slightly. This is because the implementation does not fully exploit sparsity. OpenAI's blocksparse, however, is highly optimized and written directly in CUDA code, which is incomparable. But regardless of speed, these three types of Sparse Attention should be functionally correct.

There's not much left to summarize; the article introduced and implemented three types of Sparse Attention. Besides saving video memory, Sparse Attention should be better suited for certain tasks, as associations in most tasks are primarily local and follow a "local to global" form. Especially the "locally dense and remotely sparse" nature reflected in the last Sparse Self Attention should meet the characteristics of most tasks. Readers who have relevant tasks might want to give it a try.