By 苏剑林 | April 13, 2020

Since the release of "Attention is All You Need", Transformer models based on Multi-Head Attention have become popular. The BERT model released last year pushed the popularity of the Transformer model to a new peak. Of course, the exploration of technology is endless, and incremental improvements have emerged: some improve pre-training tasks, such as XLNet's PLM and ALBERT's SOP; some improve normalization, such as the shift from Post-Norm to Pre-Norm and the removal of the beta parameter in Layer Norm in T5; some improve the model structure, such as Transformer-XL; some improve training methods, such as ALBERT's parameter sharing; and so on.

The changes above all take place outside of the Attention mechanism. In other words, they default to the rationality of the Attention mechanism itself and do not modify it. In this article, we introduce two new results: they target potential modeling bottlenecks in Multi-Head Attention and propose different solutions to improve Multi-Head Attention. Both papers come from Google and include extensive experiments, making the results quite persuasive.

No matter how small, key_size must be large

The first result comes from the article "Low-Rank Bottleneck in Multi-head Attention Models". It explicitly points out the bottleneck in representational capacity within Multi-Head Attention and proposes alleviating this bottleneck by increasing the key_size.

Multi-Head Attention

First, let's briefly review Multi-Head Attention. Readers can also refer to the previous post "A Brief Reading of 'Attention is All You Need' (Introduction + Code)". The foundation of Multi-Head Attention is naturally Single-Head Attention, also known as Scaled Dot-Product Attention, defined as follows:

\begin{equation}Attention(\boldsymbol{Q},\boldsymbol{K},\boldsymbol{V}) = softmax\left(\frac{\boldsymbol{Q}\boldsymbol{K}^{\top}}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)\boldsymbol{V}\end{equation}

where $\boldsymbol{Q}\in\mathbb{R}^{n\times d_k}, \boldsymbol{K}\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times d_k}, \boldsymbol{V}\in\mathbb{R}^{m\times d_v}$. Multi-Head Attention involves projecting $\boldsymbol{Q}, \boldsymbol{K}, \boldsymbol{V}$ using $h$ different sets of projection matrices $h$ times, performing $h$ Single-Head Attentions separately, and finally concatenating the results:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}&\boldsymbol{Q}^{(1)}=\boldsymbol{Q}\boldsymbol{W}_Q^{(1)},\boldsymbol{K}^{(1)}=\boldsymbol{K}\boldsymbol{W}_K^{(1)},\boldsymbol{V}^{(1)}=\boldsymbol{V}\boldsymbol{W}_V^{(1)},\boldsymbol{O}^{(1)}=Attention\left(\boldsymbol{Q}^{(1)},\boldsymbol{K}^{(1)},\boldsymbol{V}^{(1)}\right)\\

&\boldsymbol{Q}^{(2)}=\boldsymbol{Q}\boldsymbol{W}_Q^{(2)},\boldsymbol{K}^{(2)}=\boldsymbol{K}\boldsymbol{W}_K^{(2)},\boldsymbol{V}^{(2)}=\boldsymbol{V}\boldsymbol{W}_V^{(2)},\boldsymbol{O}^{(2)}=Attention\left(\boldsymbol{Q}^{(2)},\boldsymbol{K}^{(2)},\boldsymbol{V}^{(2)}\right)\\

&\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\vdots\\

&\boldsymbol{Q}^{(h)}=\boldsymbol{Q}\boldsymbol{W}_Q^{(h)},\boldsymbol{K}^{(h)}=\boldsymbol{K}\boldsymbol{W}_K^{(h)},\boldsymbol{V}^{(h)}=\boldsymbol{V}\boldsymbol{W}_V^{(h)},\boldsymbol{O}^{(h)}=Attention\left(\boldsymbol{Q}^{(h)},\boldsymbol{K}^{(h)},\boldsymbol{V}^{(h)}\right)\\

&\boldsymbol{O}=\left[\boldsymbol{O}^{(1)},\boldsymbol{O}^{(2)},\dots,\boldsymbol{O}^{(h)}\right]

\end{aligned}\end{equation}

The Bottleneck in Attention

In practice, $\boldsymbol{Q}, \boldsymbol{K}, \boldsymbol{V}$ usually have the same feature dimension $d_k=d_v=d$ (i.e., hidden_size), such as 768 in BERT Base. $h$ is typically chosen as 12, 16, 24, etc. After determining $d$ and $h$, the standard choice is to set the projection matrices $\boldsymbol{W}\in\mathbb{R}^{d\times (d/h)}$. This means that in each Attention Head, the original $d$ dimensions are projected down to $d/h$ dimensions, the Attention operation is performed, the output is $d/h$ dimensions, and finally, the outputs of the $h$ heads are concatenated to get a $d$-dimensional output. We usually call $d/h$ the head_size.

The critical step in Attention is:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{P}=softmax\left(\frac{\boldsymbol{Q}\boldsymbol{K}^{\top}}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)\label{eq:softmax}\end{equation}

This step describes the relationship between pairs of vectors in $\boldsymbol{Q}$ and $\boldsymbol{K}$. We can view $\boldsymbol{P}$ as a binary joint distribution (it is actually $n$ univariate distributions, but this detail is not important). If the sequence length is $n$, meaning each element can take $n$ possible values, this distribution contains a total of $n^2$ values.

However, when we project $\boldsymbol{Q}$ and $\boldsymbol{K}$ into lower dimensions, the parameter count for each is only $n \times (d/h)$. The total parameter count is $2nd/h$. Thus, Equation \eqref{eq:softmax} is equivalent to using $2nd/h$ parameters to approximate a volume that inherently has $n^2$ values. Typically, $2nd/h \ll n^2$, especially when $h$ is large. Therefore, this modeling approach "overburdens the model," which is the meaning of the "Low-Rank Bottleneck" in the original paper.

How about increasing key_size?

What is the solution? The direct thought is to increase $2nd/h$, so we either reduce the number of heads $h$ or increase the hidden_size $d$. However, more Attention Heads themselves enhance the representational power of the model, so reducing $h$ to alleviate the low-rank bottleneck might be counterproductive. Increasing $d$ would naturally enhance the overall expressiveness, but the model size and computational cost would grow dramatically, which doesn't seem like a good choice either.

Are there other ways? Yes! When we use projection matrices to map $\boldsymbol{Q}, \boldsymbol{K}, \boldsymbol{V}$ to lower dimensions, they are usually all projected to $d/h$. But in reality, their dimensions don't have to be equal. We only need the dimensions of $\boldsymbol{Q}$ and $\boldsymbol{K}$ to be identical (to perform the dot product). To distinguish them, we usually call the dimension of $\boldsymbol{Q}$ and $\boldsymbol{K}$ the key_size, and only the dimension of $\boldsymbol{V}$ is called the head_size. Changing the key_size without changing the head_size does not affect the model's hidden_size.

Therefore, the solution proposed in this paper is to increase the key_size of the model. This increases the expressiveness of Attention without changing the overall hidden_size of the model, while only slightly increasing the computational cost.

Supplementary Note:

In fact, the original paper considers simultaneously increasing key_size and head_size, then using a transformation matrix to reduce the dimension after concatenating the Multi-Head Attention outputs. However, I believe that since the concatenation and reduction step is just a linear transformation, the fundamental improvement comes from increasing the key_size. Thus, this article emphasizes the step of increasing key_size.

Furthermore, if both key_size and head_size are increased, computational cost and memory consumption increase significantly. If only key_size is increased, the additional resource consumption is much smaller.

Let's look at the experimental results

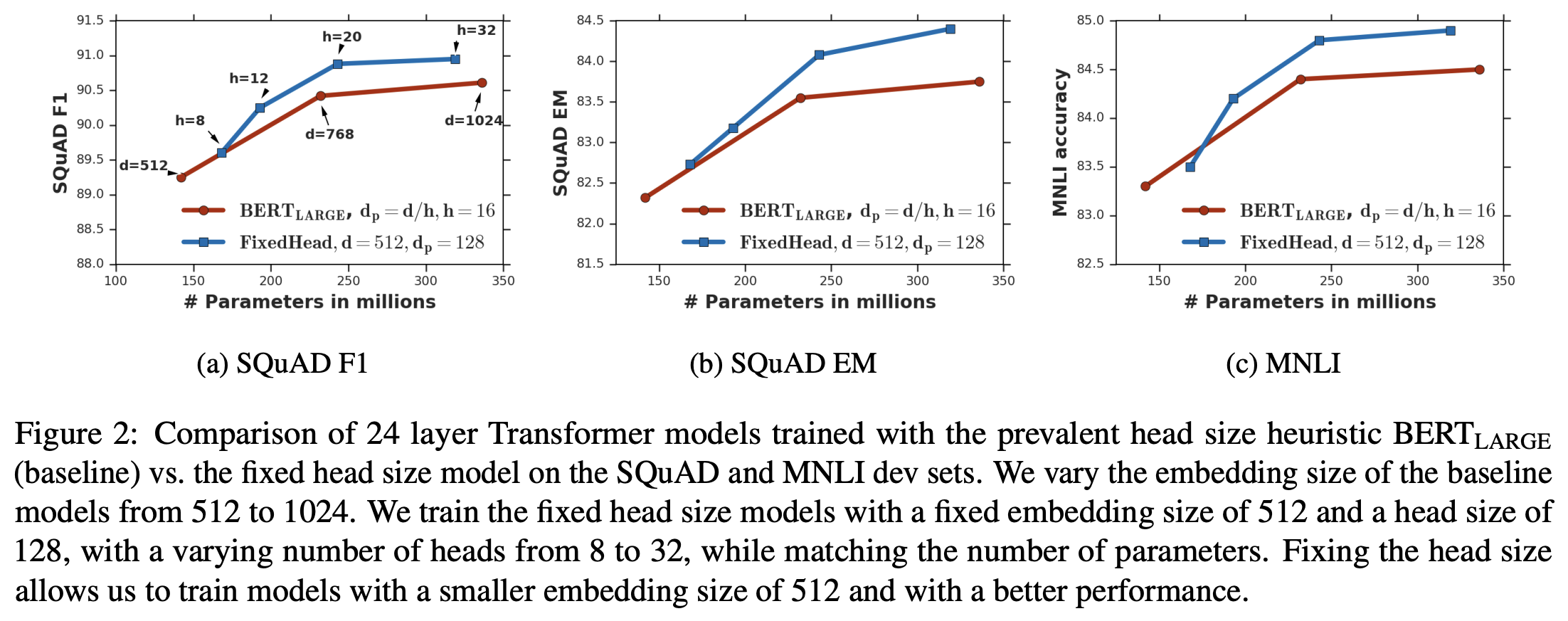

The idea of increasing key_size is very simple and easy to implement, but is it really effective? Let's look at the results from the original paper. The experiments used BERT as a baseline. There are many charts in the original paper, so it is best to read it directly, but here is a representative one:

Maintaining a larger key_size allows the model to perform better given the same parameter scale

This result shows that if we fix a relatively large key_size (e.g., 128), we can adjust the model's hidden_size and number of heads so that the parameter count is the same as the original BERT design, but the performance is better! Therefore, increasing key_size is indeed meaningful. Even if the total parameter count is adjusted back to the original size, it can still improve the model's performance to some extent. This undoubtedly provides important guidance for us when designing new Transformer models (especially small-scale ones).

Finally, we have attached two small RoBERTa models pre-trained with increased key_size. Everyone is welcome to use them (we call them RoBERTa+):

https://github.com/ZhuiyiTechnology/pretrained-models

No matter what is missing, Talking must stay

The second result for improving Multi-Head Attention comes from the paper "Talking-Heads Attention". Although this paper doesn't explicitly mention its connection to the previous one, I believe they are essentially solving the same problem but with different approaches. It points out that in current Multi-Head Attention, the computation of each head is isolated. By linking them ("Talking"), one can achieve a stronger Attention design, hence the title "Talking-Heads Attention."

From Single Distributions to Mixture Distributions

In the previous paper, we mentioned the low-rank bottleneck, which means that because key_size is too small, the representational capacity of $\boldsymbol{Q}^{(i)}{\boldsymbol{K}^{(i)}}^{\top}$ is insufficient, making it difficult for the softmax to propose a complete binary distribution. To alleviate this problem, beyond increasing key_size, is there another way? Yes, for example, the mixture distribution approach used in this paper.

A mixture distribution is the superposition (e.g., weighted average) of multiple simple distributions. It can significantly enhance the expressiveness of the original distribution. A typical example is the Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM). We know that a single Gaussian distribution is just a common simple distribution, but a Gaussian Mixture distribution formed by superimposing multiple Gaussians is a much stronger distribution. Theoretically, as long as enough Gaussians are superimposed, a GMM can approximate any probability distribution. This example tells us that if we want to increase the representational power of the distributions in Attention without increasing key_size, we can consider superimposing multiple low-rank distributions.

Where do "multiple" low-rank distributions come from? We have Multi-Head! Each head carries a low-rank distribution; we can just superimpose them. This is Talking-Heads Attention. Specifically, its form is:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}&\hat{\boldsymbol{J}}^{(1)}=\boldsymbol{Q}^{(1)}{\boldsymbol{K}^{(1)}}^{\top},\quad\hat{\boldsymbol{J}}^{(2)}=\boldsymbol{Q}^{(2)}{\boldsymbol{K}^{(2)}}^{\top},\quad\cdots,\quad\hat{\boldsymbol{J}}^{(h)}=\boldsymbol{Q}^{(h)}{\boldsymbol{K}^{(h)}}^{\top}\\

&\begin{pmatrix}\boldsymbol{J}^{(1)} \\ \boldsymbol{J}^{(2)} \\ \vdots \\ \boldsymbol{J}^{(h)}\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}\lambda_{11} & \lambda_{12}& \cdots & \lambda_{1h}\\

\lambda_{21} & \lambda_{22} & \cdots & \lambda_{2h}\\

\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\

\lambda_{h1} & \lambda_{h2} & \cdots & \lambda_{hh}

\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}\hat{\boldsymbol{J}}^{(1)} \\ \hat{\boldsymbol{J}}^{(2)} \\ \vdots \\ \hat{\boldsymbol{J}}^{(h)}\end{pmatrix}\\

&\boldsymbol{P}^{(1)}=softmax\left(\boldsymbol{J}^{(1)}\right),\boldsymbol{P}^{(2)}=softmax\left(\boldsymbol{J}^{(2)}\right),\dots,\boldsymbol{P}^{(h)}=softmax\left(\boldsymbol{J}^{(h)}\right)\\

&\boldsymbol{O}^{(1)}=\boldsymbol{P}^{(1)} \boldsymbol{V}^{(1)},\quad \boldsymbol{O}^{(2)}=\boldsymbol{P}^{(2)} \boldsymbol{V}^{(2)},\quad ,\cdots,\quad\boldsymbol{O}^{(h)}=\boldsymbol{P}^{(h)} \boldsymbol{V}^{(h)}\\

&\boldsymbol{O}=\left[\boldsymbol{O}^{(1)},\boldsymbol{O}^{(2)},\dots,\boldsymbol{O}^{(h)}\right]

\end{aligned}\end{equation}

It looks complicated, but it is actually very simple: Between "$\boldsymbol{Q}\boldsymbol{K}^{\top}$" and "softmax", use a parameter matrix $\boldsymbol{\lambda}$ to superimpose the results of various $\boldsymbol{Q}\boldsymbol{K}^{\top}$. This links the previously isolated Attention Heads, performing a simple "Talking" operation.

Two supplementary notes on the formulas above:

1. For simplicity, I omitted the scaling factor $\sqrt{d_k}$ in the formulas above. If needed, readers can add it themselves.

2. A more general version of Talking-Heads Attention allows for up-projection in the step $\boldsymbol{J}=\boldsymbol{\lambda}\hat{\boldsymbol{J}}$, i.e., superimposing more than $h$ mixture distributions, and then using another parameter matrix to project back down. However, this is not a particularly critical improvement, so it is not featured in the main text.

Let's look at the experimental results

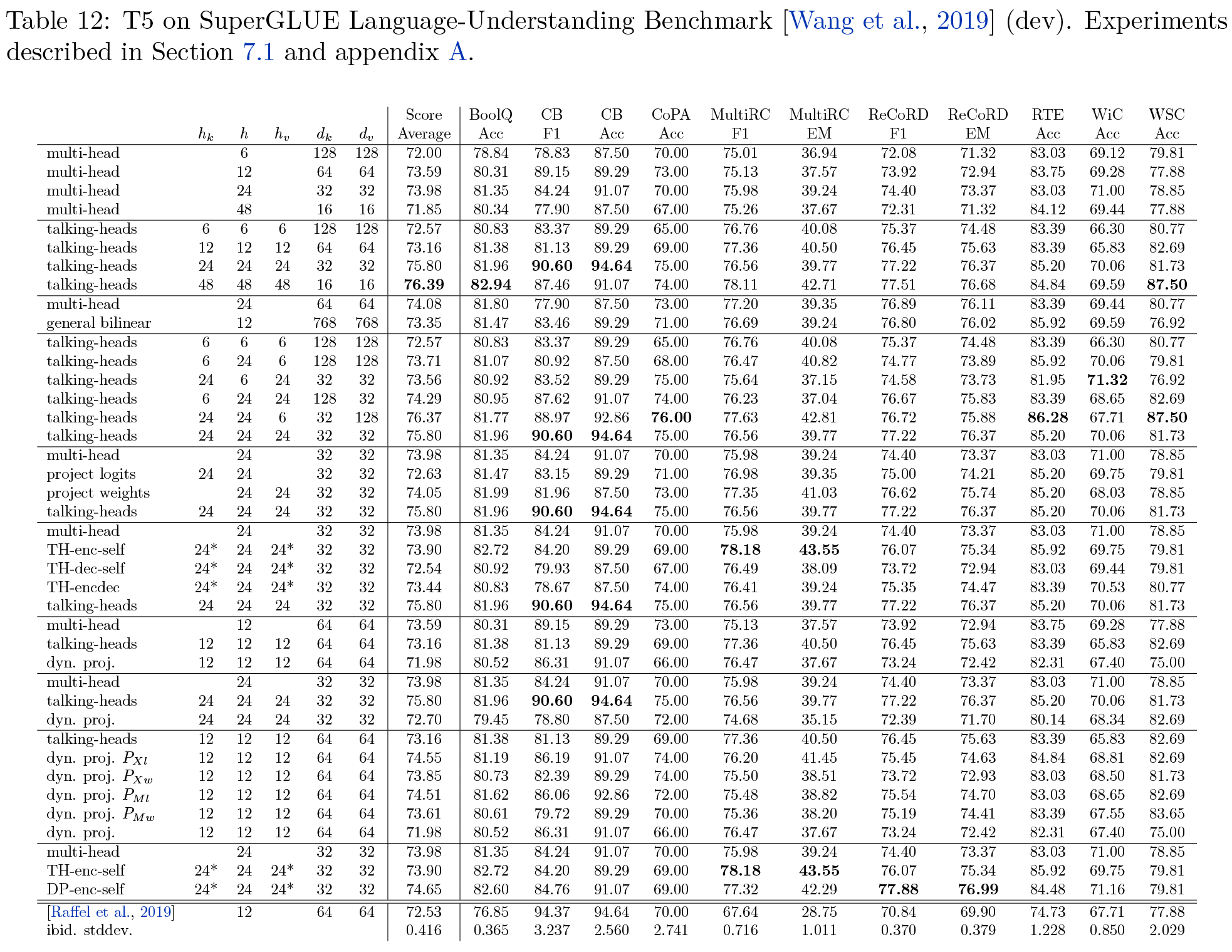

Is it really effective? Of course, the experimental results speak for themselves. The experimental lineup of this paper is unprecedentedly strong, including results based on BERT, ALBERT, and T5 clusters! As we all know, BERT, ALBERT, and T5 were all SOTA (State of the Art) models in NLP at certain points in time. T5, in particular, remains at the top of the SuperGLUE leaderboard, far ahead of the second place. Talking-Heads Attention has essentially pushed their glorious achievements to a new height!

Again, you should check the original paper for detailed experimental results. Here is a typical one:

Experimental results show that when the Talking-Head mechanism is used and hidden_size is kept constant, a larger number of heads leads to better results.

This result shows that when using Talking-Head Attention, while keeping hidden_size constant, the more heads there are (consequently, the smaller the key_size and head_size), the better the effect. This seems to contradict the conclusion of the previous paper about increasing key_size, but it actually illustrates the significant role of mixture distributions in improving distribution fitting. It can superimpose single distributions that are weakened by shrinking key_size into a distribution with much stronger fitting capabilities. Of course, this doesn't mean we should simply set key_size=1, because the computational cost would be significantly higher than the original BERT Base. In practice, a balance between performance and computation is required.

The table above is just the tip of the iceberg of the original paper's experiments. Let's look at another experimental table to feel the scale of the lineup:

Experimental results of T5 + Talking-Heads Attention on SuperGLUE

Experiments were conducted for almost every task and every combination of hyperparameters. Such a powerful experimental blitz could essentially only be done by Google. Furthermore, the entire paper has a strong "T5 Style" (readers who haven't read the T5 paper can check out "Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer"). Sure enough, one of the authors, Noam Shazeer, is also one of the authors of T5.

I just want to say that this massive experimental bombardment seems to announce to us:

"Don't doubt it, we've tuned all the parameters that need to be tuned, and our Talking-Heads Attention is the best~"

Interlude: Strange Paper Style

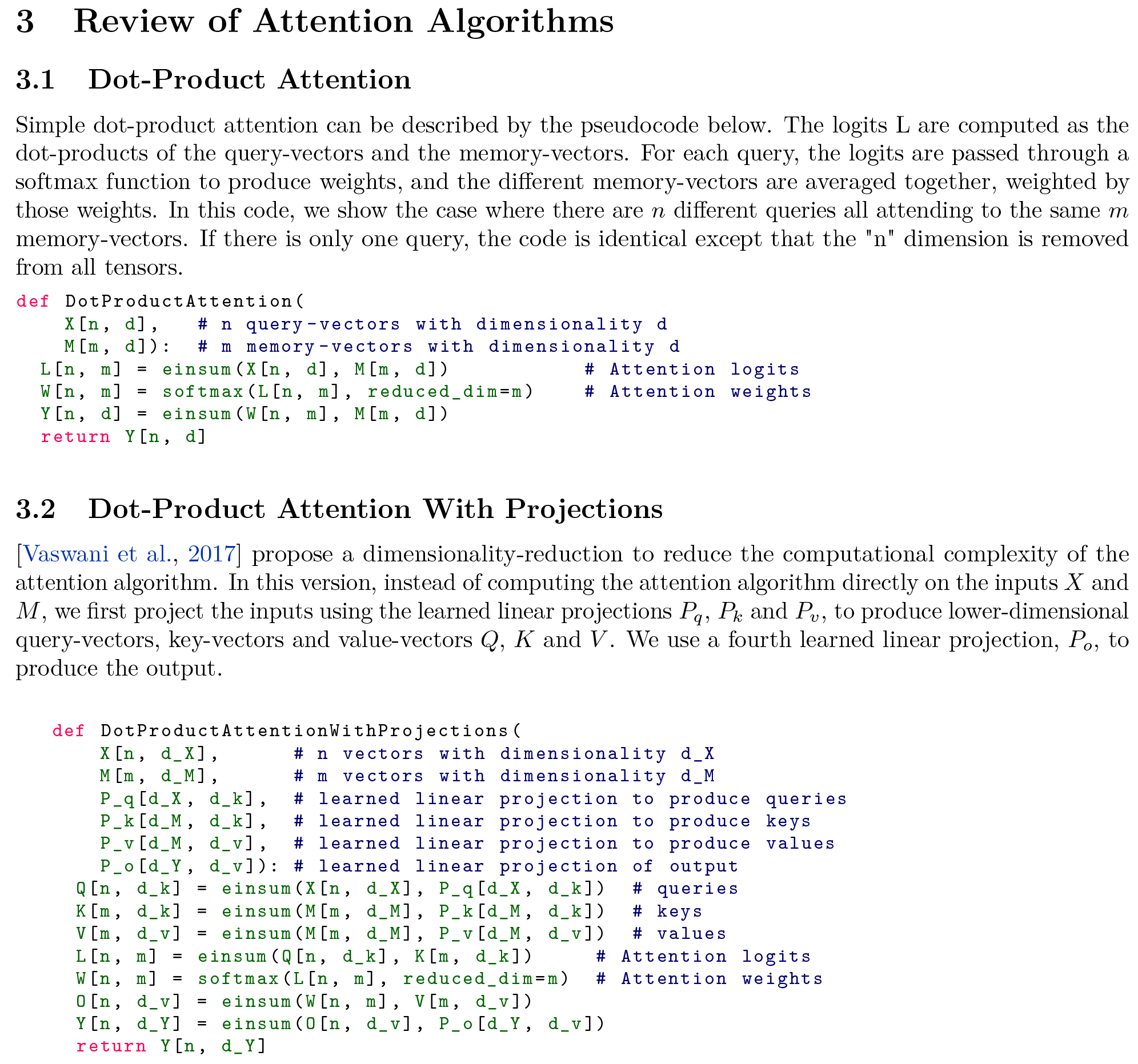

Speaking of which, when I first came across the "Talking-Heads Attention" paper on ArXiv, my first impression was that it was a trashy paper. Why? Because its style looks like this:

Pseudo-code in "Talking-Heads Attention"

Who could imagine that such a powerful paper contains not a single mathematical formula, replaced entirely by pseudo-code!! Actually, it's barely even pseudo-code; it feels more like copying Python code directly from the experiment into the main body of the paper! In my impression, only low-tier "watery" papers do this, so my first thought was that this was a fluff piece. However, only Google's big shots can afford to be so willful. If I hadn't patiently scanned it a few more times, and if I hadn't accidentally seen "T5" and other terms, and if I hadn't checked that the authors were all from Google, this powerful paper would have been treated as trash by me and sent to the recycle bin.

However, willfulness comes at a price. This paper, with such a massive experimental lineup and such effective results, has been out for over a month, but it seems to have little traction. This likely has something to do with its willful style~

Summary at the End

This article introduced two follow-up works on improving Multi-Head Attention. Although the implementation details are different, they both address the "low-rank bottleneck" problem, giving a sense of "converging paths." Both works come from Google and follow-up with rich experiments, so the results are relatively persuasive. Readers working on structural improvements to models can refer to them.