By 苏剑林 | March 15, 2021

WGAN, or Wasserstein GAN, is considered a major theoretical breakthrough in the history of GANs. It transformed the measure of the two probability distributions in GANs from f-divergence to Wasserstein distance, making the training process of WGAN more stable and generally resulting in better generation quality. Wasserstein distance is related to Optimal Transport and belongs to the class of Integral Probability Metrics (IPMs). These probability measures usually possess superior theoretical properties, which is why the emergence of WGAN attracted many researchers to understand and study GAN models through the lens of Optimal Transport and IPMs.

However, a recent paper on arXiv, "Wasserstein GANs Work Because They Fail (to Approximate the Wasserstein Distance)", points out that although WGAN was derived from the theory of Wasserstein distance, successful WGANs today do not actually approximate the Wasserstein distance well. On the contrary, if we perform a better approximation of the Wasserstein distance, the performance actually gets worse. In fact, I have long had this doubt—that Wasserstein distance itself does not inherently manifest a necessity to improve GAN performance. The conclusion of this paper confirms this suspicion, meaning the reason GANs succeed remains quite enigmatic.

Basics and Review

This article is a discussion of the WGAN training process and is not intended as an introductory piece. For beginners, please refer to "The Art of Mutual Confrontation: From Zero to WGAN-GP". For the connection between f-divergence and GANs, see "Introduction to f-GAN: The Production Workshop of GAN Models" and "Designing GANs: Another GAN Production Workshop". For the theoretical derivation of WGAN, see "From Wasserstein Distance and Duality Theory to WGAN". For an analysis of the GAN training process, you can also refer to "Optimization Algorithms from a Dynamical Perspective (IV): The Third Stage of GAN".

Generally speaking, GAN corresponds to a min-max process:

$$ \min_G \max_D \mathcal{L}(G, D) $$

Of course, the loss functions for the discriminator and the generator might be different in practice, but the above form is sufficiently representative. The original GAN is usually called vanilla GAN, and its form is:

\begin{equation}\min_G \max_D \mathbb{E}_{x\sim p(x)}\left[\log D(x)\right] + \mathbb{E}_{z\sim q(z)}\left[\log (1 - D(G(z)))\right]\label{eq:v-gan}\end{equation}

As proved in "Towards Principled Methods for Training Generative Adversarial Networks", "Amazing Wasserstein GAN", or related GAN articles on this blog, vanilla GAN is effectively minimizing the JS divergence between two distributions. JS divergence is a type of f-divergence, and all f-divergences share a problem: when two distributions have almost no overlap, the divergence is a constant. This implies the gradient is zero, and since we use gradient descent for optimization, it means we cannot optimize effectively. Thus, WGAN was born, utilizing Wasserstein distance to design a new GAN:

\begin{equation}\min_G \max_{\Vert D\Vert_{L}\leq 1} \mathbb{E}_{x\sim p(x)}\left[D(x)\right] - \mathbb{E}_{z\sim q(z)}\left[D(G(z))\right]\label{eq:w-gan}\end{equation}

The obvious difference from previous GANs is that WGAN explicitly adds a Lipschitz constraint $\Vert D\Vert_{L}\leq 1$ to the discriminator $D$. Since Wasserstein distance is well-defined for almost any two distributions (even if they don't overlap), WGAN theoretically solves problems like gradient vanishing and training instability found in traditional f-divergence-based GANs.

There are two main schemes for adding the Lipschitz constraint to the discriminator: first is Spectral Normalization (SN), see "Lipschitz Constraints in Deep Learning: Generalization and Generative Models" (now many GANs, not just WGAN, incorporate SN into the discriminator or even the generator for stability); second is Gradient Penalty (GP), which includes 1-centered penalty (WGAN-GP) and 0-centered penalty (WGAN-div), as seen in "WGAN-div: A Quiet WGAN Gap-Filler". Current results suggest that zero-centered penalty has better theoretical properties and effects.

Performance ≠ Approximation

The phenomenon that "WGAN does not approximate Wasserstein distance well" is not being noticed for the first time. For example, a 2019 paper "How Well Do WGANs Estimate the Wasserstein Metric?" systematically discussed this point. The paper highlighted here further identifies the link between WGAN performance and the degree of Wasserstein distance approximation through strictly controlled experiments.

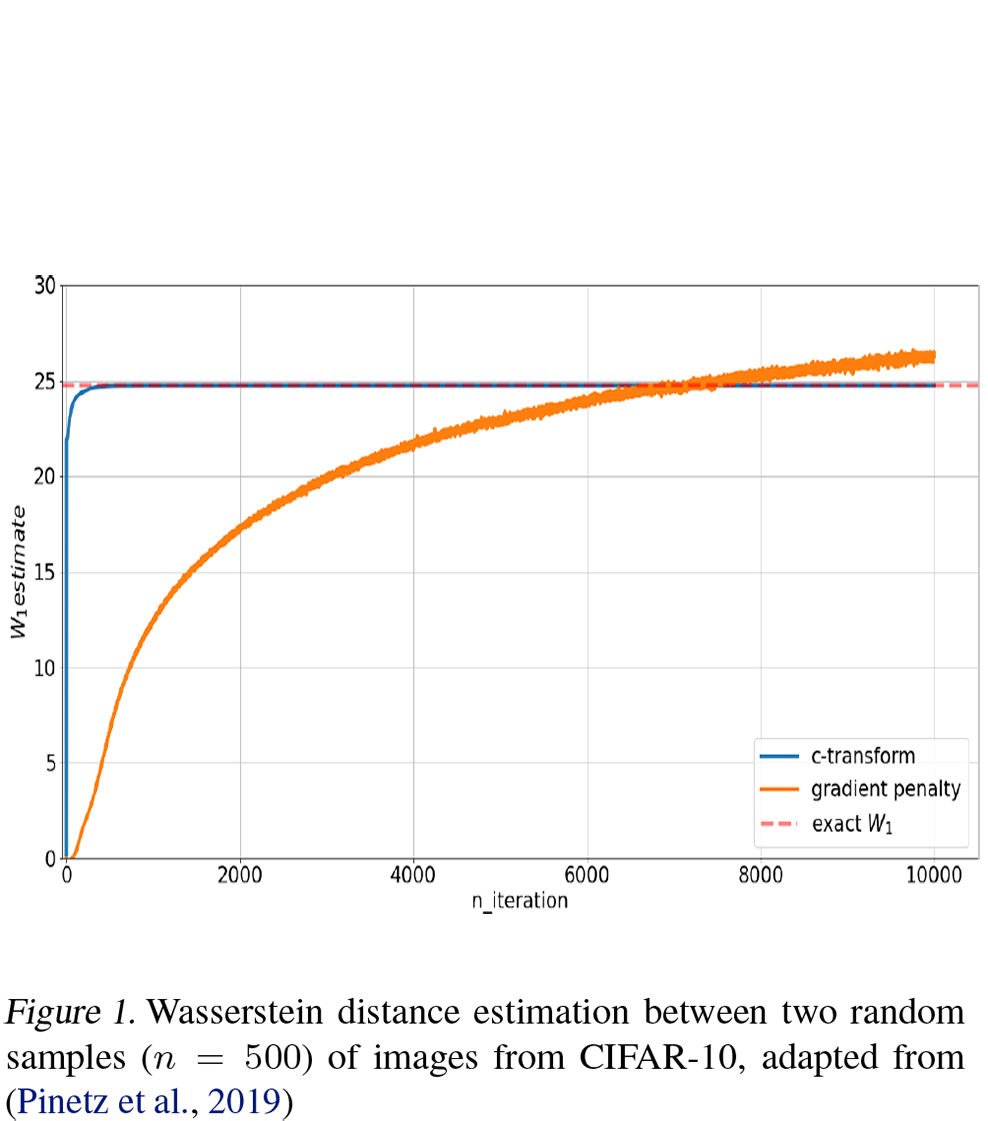

First, the paper compared the performance of Gradient Penalty (GP) with a method called c-transform in implementing WGAN. The c-transform method, also proposed in "How Well Do WGANs Estimate the Wasserstein Metric?", approximates Wasserstein distance much better than Gradient Penalty. The following two figures illustrate this:

Static testing of WGAN-GP, c-transform and Wasserstein distance approximation degree

WGAN-GP, c-transform and Wasserstein distance approximation degree during the training process

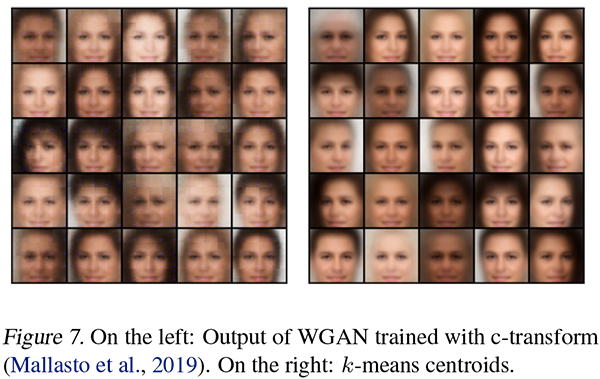

However, the generation quality of c-transform is actually inferior to Gradient Penalty:

Comparison of generation results between WGAN-GP and c-transform

Of course, the original author's choice of this specific image is somewhat comical; in fact, WGAN-GP results can be much better than the image on the right. Thus, we can temporarily conclude:

1. Well-performing WGANs do not approximate Wasserstein distance well during training;

2. Better approximation of Wasserstein distance does not help improve generation performance.

Theory ≠ Experiment

Now let's consider where the problem lies. We know that whether it is vanilla GAN $\eqref{eq:v-gan}$, WGAN $\eqref{eq:w-gan}$, or other GANs, they share two common characteristics during experimentation:

1. $\min$ and $\max$ are trained alternately;

2. Only a random batch is selected for training each time.

What are the problems with these two points?

First, almost all GANs are written as $\min_G \max_D$ because, theoretically, one needs to accurately complete $\max_D$ first and then perform $\min_G$ to be optimizing the probability measure corresponding to the GAN. If they are just optimized alternately, it is theoretically impossible to accurately approach the probability measure. Even though WGAN is not afraid of vanishing gradients because it uses Wasserstein distance—allowing for more discriminator steps (or higher learning rates for $D$) during alternating training—it still cannot precisely approximate Wasserstein distance. This is one source of the discrepancy.

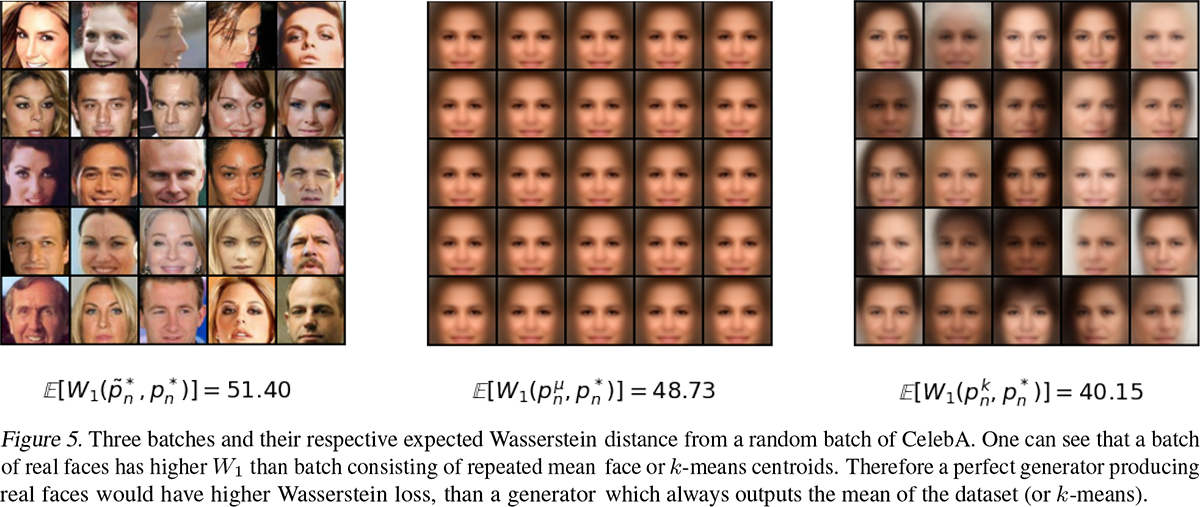

Second, training on a randomly sampled batch rather than the full set of training samples leads to a result where "the Wasserstein distance between two random batches in the training set is actually larger than the Wasserstein distance between a training set batch and its average sample," as shown in the figure below:

Left: batch of real samples, Middle: average sample, Right: sample cluster center. In terms of Wasserstein distance, real samples are worse than the middle two blurry samples.

This shows that in batch-based training, if you hope to obtain more realistic samples, you are certainly not optimizing the Wasserstein distance. If you are precisely optimizing the Wasserstein distance, you will not get realistic samples, because the Wasserstein distance for blurry average samples is actually smaller.

Math ≠ Vision

From a mathematical perspective, the properties of Wasserstein distance are indeed very elegant; in a sense, it is the best way to measure the gap between any two distributions. However, math is math, and the most "fatal" aspect of Wasserstein distance is that it depends on a specific metric:

\begin{equation}\mathcal{W}[p,q]=\inf_{\gamma\in \Pi[p,q]} \iint \gamma(x,y) d(x,y) dxdy\end{equation}

That is, we need to provide a function $d(x,y)$ that measures the gap between two samples. However, for many scenarios, such as two images, designing the metric function itself is the hardest of hard problems. WGAN directly uses Euclidean distance $d(x,y)=\Vert x - y\Vert_2$. While mathematically reasonable, it is visually unreasonable; two images our eyes perceive as similar do not necessarily have a smaller Euclidean distance. Therefore, if one approximates Wasserstein distance too accurately, it actually results in poorer visual quality. The original paper also conducted experiments showing that using c-transform to better approximate Wasserstein distance results in generation effects similar to K-Means cluster centers, and K-Means also happens to use Euclidean distance as its metric:

Similarity between c-transform results and K-Means

Thus, the reason for WGAN's success is now very mysterious: WGAN was derived based on Wasserstein distance, but its implementation has a gap from actual Wasserstein distance, and this gap might exactly be the key to WGAN's success. The original paper argues that the most critical aspect of WGAN is the introduction of the Lipschitz constraint. Adding a Lipschitz constraint (via Spectral Normalization or Gradient Penalty) to almost any GAN variant more or less improves performance and stability. Therefore, the Lipschitz constraint is the real point of improvement, rather than the imagined Wasserstein distance.

But this is more of a conclusion than a theoretical analysis. It seems that deep understanding of GANs still has a long way to go~

A Simple Summary

This article primarily shared a recent paper pointing out that whether Wasserstein distance is approximated well has no necessary connection with WGAN's performance. How to better understand the theory and practice of GANs remains a difficult task~