By 苏剑林 | July 19, 2021

As many of you know, from SimBERT to SimBERTv2 (RoFormer-Sim), we have established a fairly decent baseline model for Chinese text similarity tasks. However, both SimBERT and RoFormer-Sim are essentially "weakly supervised" models, similar to unsupervised ones; we cannot expect a purely weakly supervised model to achieve effects that perfectly align with human cognition. Therefore, to further improve the performance of RoFormer-Sim, we attempted to use some open-source annotated data to assist in training. This article introduces our exploration process.

Some readers might think: Is there anything to talk about regarding supervised training? Isn't it just direct training? While that's easy to say, it's not actually that "obvious and straightforward." There are still some "minefields," so this article can be considered a simple "mine-clearing guide."

Previous Recollection

I have found that since the release of SimBERT, the most frequent question from readers is probably:

Why is the similarity between "I like Beijing" and "I don't like Beijing" so high? Aren't their meanings opposite?

This is especially true after the release of RoFormer-Sim; similar questions appear almost every week or two. Furthermore, not only in my own "Scientific Spaces" exchange group, but also in other NLP-related groups, similar questions pop up from time to time, indicating that this doubt is widespread.

So, how should we understand this?

First, the cognition of "opposite meaning" is incorrect. From the perspective of similarity, there are only "similar" and "not similar" distinctions; there is no such thing as "opposite." In principle, no two sentences are absolutely unrelated, so theoretically, the similarity of any two sentences is not zero, let alone "opposite," which lacks a clear definition. Quite the contrary, the "antonyms" we usually think of are objectively very similar words from a certain perspective. For example, "like" and "hate" share many commonalities: both are verbs, both describe emotional tendencies, and their usage is similar. So how can we say these two words are "not similar at all" or even "opposite"? When we call them antonyms, we mean they are in an opposing relationship within a very small dimension. Note that it is only *one* dimension, not all. This means our cognition itself is subjective (with so many dimensions being similar and only one being dissimilar, we call them "antonyms"—isn't that subjective?).

Similarly, in my understanding, from an objective perspective, "I like Beijing" and "I don't like Beijing" are very similar, so it is reasonable for the model to give a high similarity score; giving a low score would be unreasonable. Of course, I am not saying that they are similar in every scenario—they do indeed have opposing dimensions. The problem is that what unsupervised and weakly supervised learning produces are relatively objective results. If we believe "I like Beijing" and "I don't like Beijing" are not similar, it means we have subjectively picked out the dimensions we want to compare, rather than considering all objective dimensions. Since this is a subjective human act, we should not expect unsupervised or weakly supervised methods to learn it; the best way is to use annotated data for supervised learning.

Therefore, to put it bluntly:

The model is not wrong; the person is. If the person insists they are not wrong, then please use supervised learning with annotated data to tell the model it is wrong.

Classification

Through the discussion above, we should understand the necessity of supervised labeling. Not all problems can be solved through unsupervised or weakly supervised means. If one insists on a non-supervised solution, the cost might be far greater than labeling a few pieces of data.

Regarding Chinese human-annotated data for similarity, there are currently three types collected:

1. Yes/No Type: This is the most common type. The main format is "(Sentence 1, Sentence 2, Is Similar)". The ATEC, BQ, LCQMC, and PAWSX datasets collected here are of this type;

2. NLI Type: NLI stands for Natural Language Inference. The sample format is "(Sentence 1, Sentence 2, Entailment/Neutral/Contradiction)". This can be seen as a more granular similarity dataset. Currently, Chinese NLI datasets are mostly translated from English versions, with links at CNSD;

3. Scoring Type: This is the most precise similarity corpus, formatted as "(Sentence 1, Sentence 2, Similarity Level)". This degree is generally a finer-grained scale than 0/1. Currently, the Chinese dataset available is STS-B, which is also translated from English.

Since the first two types have larger volumes, for convenience, we directly set a threshold to convert the third type (STS-B) into the first type. Thus, we utilize two data formats: 1. Binary classification of sentence pairs; 2. Three-way classification of sentence pairs.

Unexpected

As mentioned at the beginning, even with supervised training, it is not "obvious and straightforward." This is mainly because the choice of training method was somewhat unexpected. For simplicity, let's start with binary classification training samples.

Assume the sentence vectors obtained after two sentences pass through the encoder are $u$ and $v$. Since we usually use their cosine value $\cos(u,v) = \frac{\langle u, v \rangle}{\|u\|\|v\|}$ to rank similarity during the retrieval phase, a natural idea would be to design a loss function based on $\cos(u,v)$. Some easily conceived ones include:

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

&t\cdot (\cos(u,v) - 1)^2 + (1 - t)\cdot \cos^2(u,v) \\

&t\cdot (\cos(u,v) - 1)^2 + (1 - t)\cdot (\cos(u,v) + 1)^2 \\

&t\cdot \max(0.9 - \cos(u,v), 0) + (1-t)\cdot \max(\cos(u,v) - 0.1, 0)

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

where $t \in \{0, 1\}$ is the label for the sentence pair. These loss functions generally aim to make $\cos(u,v)$ for positive samples as large as possible and for negative samples as small as possible.

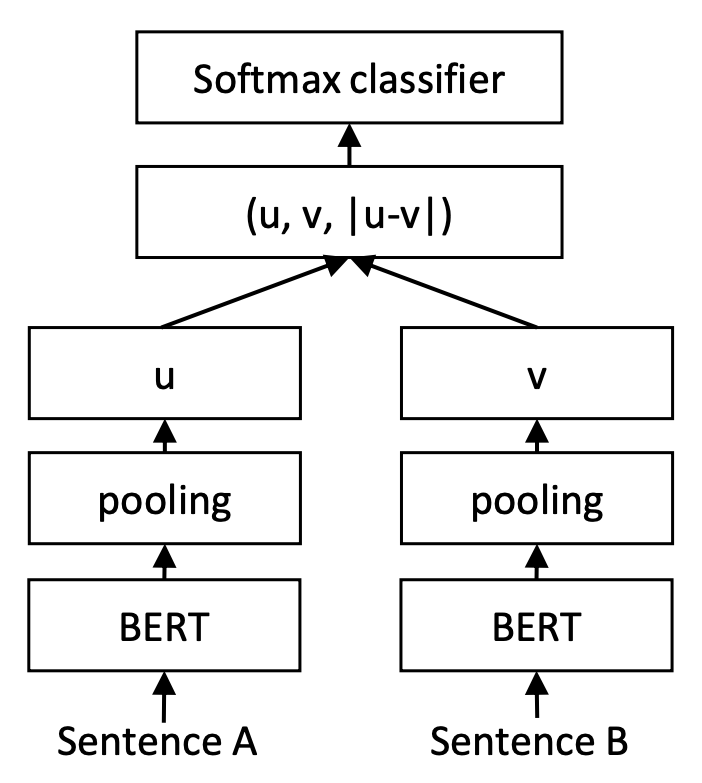

However, in my experiments, these training schemes—where training and prediction are consistent—actually performed worse than a scheme that appears inconsistent, which originated from InferSent and was subsequently adopted by Sentence-BERT. Specifically, Sentence-BERT concatenates $u, v, |u-v|$ (where $|u-v|$ refers to the vector formed by taking the absolute value of each element of $u-v$) as features, followed by a fully connected layer for binary classification (or three-way classification for NLI datasets).

Sentence-BERT Training Phase

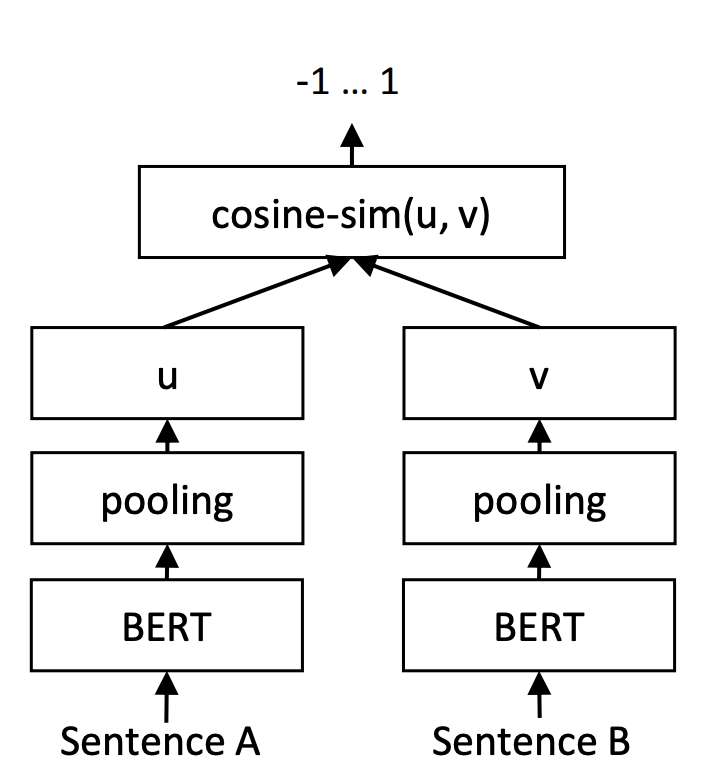

Sentence-BERT Prediction Phase

Of course, this is just the training scheme. When using it, sentence vectors are still extracted, and cosine similarity is used for retrieval. Thus, the scheme used by InferSent and Sentence-BERT is actually an inconsistent training and prediction scheme: $\cos(u,v)$ is not directly involved during training, yet $\cos(u,v)$ can be used for retrieval during prediction with quite good performance. This is indeed unexpected.

Behind Closed Doors

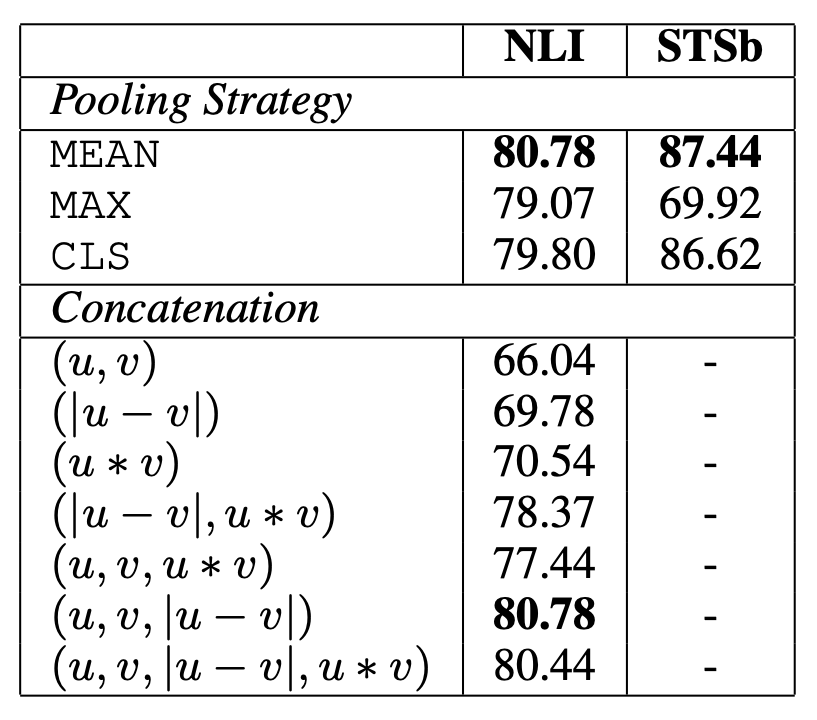

I was also puzzled by this. I noticed that in the Sentence-BERT paper, they compared the final effects of different feature concatenation methods, showing that $u, v, |u-v|$ concatenation yields the best results. If only part of them is kept, the performance drops significantly, as shown in the table below.

Experimental results of different concatenation features

Inspired by this table, I "concocted" an explanation. First, we know that humans are very "picky," especially for similarity tasks; we usually believe that only very strict similarity counts as similarity. However, our training data is often not that precise. On one hand, the labels themselves might contain noise; on the other hand, for some sample pairs, annotators might mark them as positive because they share the same topic rather than the same semantics. That is to say, annotated data is often not as strict as we require. If we directly use the labels to learn our ranking metric, it might introduce unexpected bias.

Looking back at the approach of concatenating $u, v, |u-v|$ followed by a fully connected layer, its scoring function is equivalent to:

\begin{equation}s = \langle u, w_1\rangle + \langle v, w_2\rangle + \langle |u-v|, w_3\rangle\end{equation}

where $w_1, w_2, w_3$ are the corresponding parameter vectors. For the first two terms, a large score for $\langle u, w_1\rangle + \langle v, w_2\rangle$ does not necessarily mean $u$ and $v$ are close; similarly, a small score doesn't mean they are far apart. Their role is more like a "topic classification" model used to identify if the topics of $u$ and $v$ are consistent. For the third term, we know $|u-v|=0 \Leftrightarrow u=v$, so the third term has the ability to judge the proximity of the two vectors, perhaps representing true "semantic similarity."

Taken together, we can consider that the approach of concatenating $u, v, |u-v|$ followed by a fully connected layer includes both the score for judging topic consistency and the score for semantic similarity. It separates "topic" from "semantics," enhancing the model's fault tolerance to data, which allows the eventually learned vectors to reflect more pure and precise "semantics."

Fish and Bear's Paw

Through the Sentence-BERT scheme and open-source similarity datasets, we can learn a fairly good sentence vector model (i.e., a retrieval model). Extracting features from it and using cosine similarity as a metric yields good results. But the problem is that SimBERT and RoFormer-Sim were never meant to be pure retrieval models; they hope to "have their cake and eat it too"—having both good retrieval effects and the ability to generate similar sentences.

To this end, after training a Sentence-BERT using the method above, we applied the scheme introduced in "SimBERTv2 is Here! RoFormer-Sim Model Integrating Retrieval and Generation" to distill the retrieval effect of Sentence-BERT into RoFormer-Sim. This improves the retrieval performance while preserving the capability for similar sentence generation. Moreover, distillation between models of the same size often yields a slight performance boost. Thus, the retrieval performance of our distilled RoFormer-Sim is actually better than that of the directly trained Sentence-BERT.

Performance Demo

We provide the RoFormer-Sim weights trained with annotated data below (weights with the "-ft" suffix):

https://github.com/ZhuiyiTechnology/roformer-sim

Below are the test results (on test sets) for several tasks from "Which Unsupervised Semantic Similarity Method is Stronger? A Comprehensive Comparison":

\[

\begin{array}{c|ccccc}

\hline

& \text{ATEC} & \text{BQ} & \text{LCQMC} & \text{PAWSX} & \text{STS-B} \\

\hline

\text{RoFormer-Sim} & 39.27 & 48.31 & 72.30 & 6.70 & 71.75 \\

\text{RoFormer-Sim-FT} & 51.71 & 73.48 & 79.56 & 62.84 & 78.28 \\

\hline

\text{RoFormer-Sim-small} & 37.08 & 46.83 & 71.27 & 5.8 & 71.29 \\

\text{RoFormer-Sim-FT-small} & 51.21 & 73.09 & 78.88 & 56.41 & 76.33 \\

\hline

\end{array}

\]

As can be seen, there is a significant improvement, and the "small" version also delivers an impressive performance. Of course, since this is supervised training, improvement is inevitable; the comparison in this table isn't the main point. For users, having an available model is what matters, regardless of how it was created. Readers might be more concerned about whether this new model solves previous "pain points." For example, can it differentiate between "I like Beijing" and "I don't like Beijing"? Let's look at some examples (base version; the small version results are almost identical):

>>> similarity(u'今天天气不错', u'今天天气很好')

0.9769838

>>> similarity(u'今天天气不错', u'今天天气不好')

0.62359834

>>> similarity(u'我喜欢北京', u'我很喜欢北京')

0.9921096

>>> similarity(u'我喜欢北京', u'我不喜欢北京')

0.5291042

>>> similarity(u'电影不错', u'电影很好')

0.96764225

>>> similarity(u'电影不错', u'电影不好')

0.6312722

>>> similarity(u'红色的苹果', u'绿色的苹果')

0.6974633

>>> similarity(u'给我推荐一款红色的车', u'给我推荐一款黑色的车')

0.7191832

>>> similarity(u'给我推荐一款红色的车', u'推荐一辆红车')

0.9866457

>>> similarity(u'给我推荐一款红色的车', u'麻烦来一辆红车')

0.9460306

From the examples, we can see that after supervised training, the model indeed reflects similarity scores that align more with common human cognition. For instance, the similarity drops significantly after adding the word "not" (不). Through comparison, we found that this effect is primarily brought about by the NLI dataset. Also, it becomes more sensitive to colors like "red" and "black," as shown in the last three examples, indicating that its retrieval ranking results align better with intent recognition scenarios.

Summary

This article introduced the process of enhancing RoFormer-Sim using annotated data and open-sourced the corresponding trained models, providing a better baseline for Chinese text similarity models.