By 苏剑林 | December 12, 2023

Previously, in articles like "Pathways to Transformer Upgrades: 3. From Performer to Linear Attention" and "Why are Current LLMs All Decoder-only Architectures?", we explored the Attention mechanism from the perspective of the "rank" of the Attention matrix. We once judged that the critical reason why Linear Attention is inferior to Standard Attention is the "low-rank bottleneck." However, while this explanation may hold for bidirectional Encoder models, it is difficult to apply to unidirectional Decoder models. This is because the upper triangular part of the Decoder's Attention matrix is masked, and the remaining lower triangular matrix is necessarily full-rank. Since it is already full-rank, the low-rank bottleneck problem seemingly no longer exists.

Therefore, the "low-rank bottleneck" cannot completely explain the performance deficiencies of Linear Attention. In this article, I attempt to seek an explanation from another angle. Simply put, compared to Standard Attention, Linear Attention has a harder time "focusing attention," making it difficult to accurately locate key tokens. This is likely the main reason why its performance is slightly inferior.

In the article "Looking at the Scale Operation of Attention from Entropy Invariance," we examined the Attention mechanism from the perspective of "focusing attention." At that time, we used information entropy as a measure of "degree of concentration"—the lower the entropy, the more likely the Attention is to concentrate on a specific token.

However, for general Attention mechanisms, the Attention matrix may be non-normalized, such as the GAU module introduced in "FLASH: Perhaps the Most Interesting Efficient Transformer Design Recently" and the $l_2$ normalized Attention introduced in "A Theoretical Flaw and Countermeasure for Relative Position Encoding Transformers." Furthermore, from the more general Non-Local Neural Networks perspective, the Attention matrix is not even necessarily non-negative. These non-normalized or non-positive Attention matrices are naturally not suitable for information entropy, as information entropy is intended for probability distributions.

To this end, we consider the $l_1/l_2$ form of the sparsity metric introduced in "How to Measure the Sparsity of Data?":

\begin{equation}S(x) = \frac{\mathbb{E}[|x|]}{\sqrt{\mathbb{E}[x^2]}}\end{equation}This metric is similar to information entropy: a smaller $S(x)$ implies that the corresponding random vector is sparser. Greater sparsity means it is more likely for "one to dominate," which corresponds to a one-hot distribution in probability. Unlike information entropy, it is applicable to general random variables or vectors.

For the attention mechanism, we denote $\boldsymbol{a} = (a_1, a_2, \cdots, a_n)$, where $a_j \propto f(\boldsymbol{q}\cdot\boldsymbol{k}_j)$. Then:

\begin{equation}S(\boldsymbol{a}) = \frac{\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{k}}[|f(\boldsymbol{q}\cdot\boldsymbol{k})|]}{\sqrt{\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{k}}[f^2(\boldsymbol{q}\cdot\boldsymbol{k})]}}\end{equation}Next, we consider the limit $n \to \infty$. Assume $\boldsymbol{k} \sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{\mu}, \sigma^2\boldsymbol{I})$, then we can set $\boldsymbol{k} = \boldsymbol{\mu} + \sigma \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}$, where $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon} \sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})$. Thus:

\begin{equation}S(\boldsymbol{a}) = \frac{\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}[|f(\boldsymbol{q}\cdot\boldsymbol{\mu} + \sigma\boldsymbol{q}\cdot\boldsymbol{\varepsilon})|]}{\sqrt{\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}[f^2(\boldsymbol{q}\cdot\boldsymbol{\mu} + \sigma\boldsymbol{q}\cdot\boldsymbol{\varepsilon})]}}\end{equation}Note that the distribution $\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})$ followed by $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}$ is an isotropic distribution. Following the same simplification logic derived in "Angular Distribution of Two Random Vectors in n-dimensional Space," due to isotropy, the mathematical expectation related to $\boldsymbol{q}\cdot\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}$ only depends on the norm of $\boldsymbol{q}$ and is independent of its direction. Therefore, we can simplify $\boldsymbol{q}$ to $(\Vert\boldsymbol{q}\Vert, 0, 0, \cdots, 0)$. Then the mathematical expectation over $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}$ can be simplified to:

\begin{equation}S(\boldsymbol{a}) = \frac{\mathbb{E}_{\varepsilon}[|f(\boldsymbol{q}\cdot\boldsymbol{\mu} + \sigma\Vert\boldsymbol{q}\Vert\varepsilon)|]}{\sqrt{\mathbb{E}_{\varepsilon}[f^2(\boldsymbol{q}\cdot\boldsymbol{\mu} + \sigma\Vert\boldsymbol{q}\Vert\varepsilon)]}}\end{equation}where $\varepsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0, 1)$ is a random scalar.

Now we can calculate and compare some common forms of $f$. Currently, the most commonly used Attention mechanism is $f=\exp$. In this case, calculating the expectation is just a routine one-dimensional Gaussian integral, which easily yields:

\begin{equation}S(\boldsymbol{a}) = \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2}\sigma^2\Vert\boldsymbol{q}\Vert^2\right)\end{equation}As $\sigma \to \infty$ or $\Vert\boldsymbol{q}\Vert \to \infty$, $S(\boldsymbol{a}) \to 0$ in both cases. This means that, theoretically, Standard Attention can indeed become arbitrarily sparse to "focus attention." At the same time, this tells us how to make attention more concentrated: increase the norm of $\boldsymbol{q}$, or increase the variance between the different $\boldsymbol{k}$'s—in other words, increase the gap between $\boldsymbol{k}$'s.

Another example is GAU (Gated Attention Unit), which I favor. When it was initially proposed, it used $f=\text{relu}^2$ (though I later reverted it back to Softmax when using it myself; refer to "FLASH: Perhaps the Most Interesting Efficient Transformer Design Recently" and "It is Said that Attention and Softmax are a Better Match"). In this case, the integral is not as simple as $f=\exp$, but it can be calculated explicitly using Mathematica. The result is:

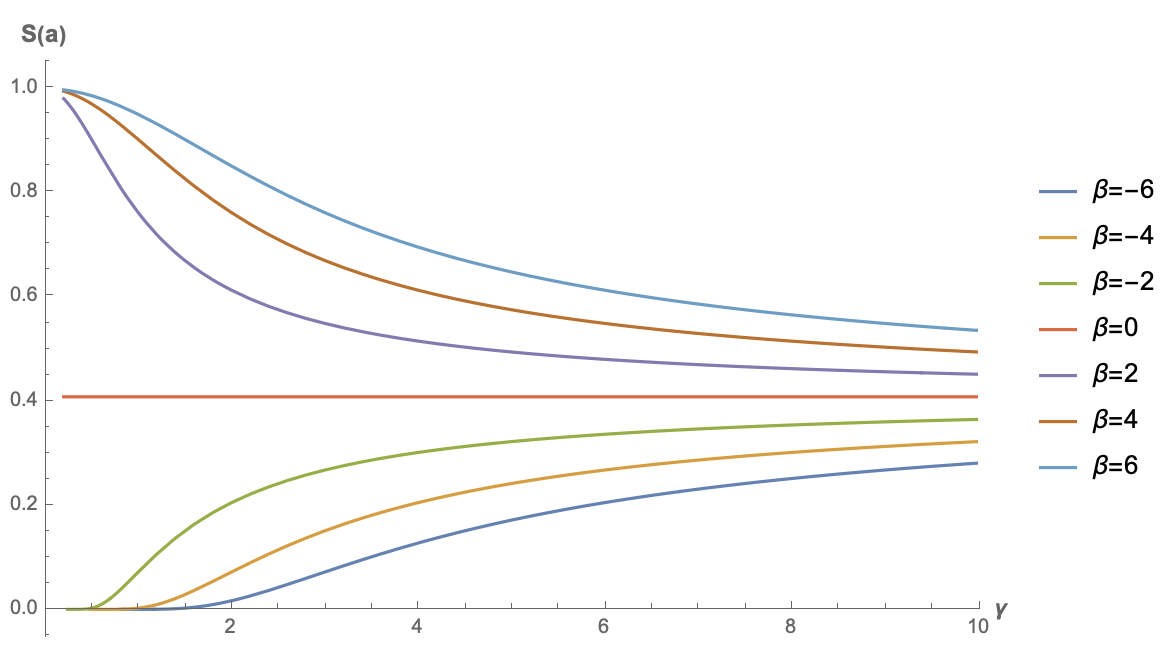

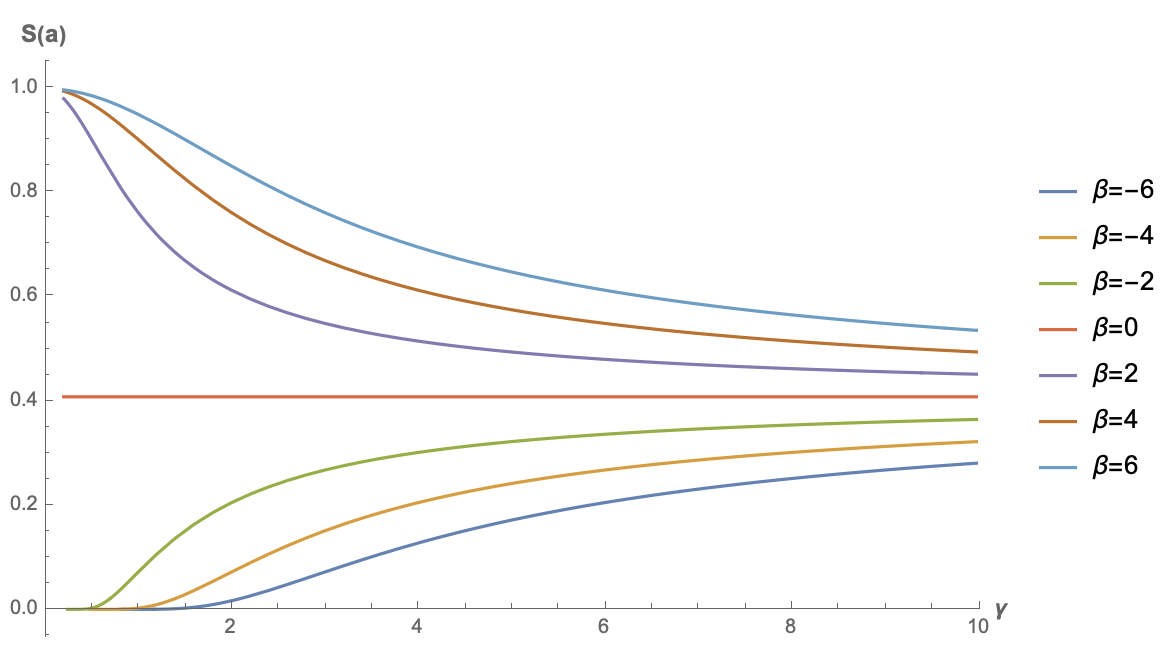

\begin{equation}S(\boldsymbol{a}) =\frac{e^{-\frac{\beta ^2}{2 \gamma ^2}} \left(\sqrt{2} \beta \gamma +\sqrt{\pi } e^{\frac{\beta ^2}{2 \gamma ^2}} \left(\beta ^2+\gamma ^2\right) \left(\text{erf}\left(\frac{\beta }{\sqrt{2} \gamma }\right)+1\right)\right)}{\sqrt[4]{\pi } \sqrt{2 \sqrt{2} \beta \gamma e^{-\frac{\beta ^2}{2 \gamma ^2}} \left(\beta ^2+5 \gamma ^2\right)+2 \sqrt{\pi } \left(\beta ^4+6 \beta ^2 \gamma ^2+3 \gamma ^4\right) \left(\text{erf}\left(\frac{\beta }{\sqrt{2} \gamma }\right)+1\right)}}\end{equation}where $\beta = \boldsymbol{q}\cdot\boldsymbol{\mu}, \gamma = \sigma\Vert\boldsymbol{q}\Vert$. The formula looks terrifying, but it doesn't matter; we can just plot it:

Sparsity curve for relu2 attention

It can be seen that only when $\beta < 0$ does the sparsity of the original GAU have a chance to approach 0. This is also intuitive: only when the bias term is less than 0 is there a greater chance for the $\text{relu}$ result to be 0, thereby achieving sparsity. This result also indicates that, unlike the $f=\exp$ of standard attention, the bias term of $\boldsymbol{k}$ might have a positive effect for the $f=\text{relu}^2$ GAU.

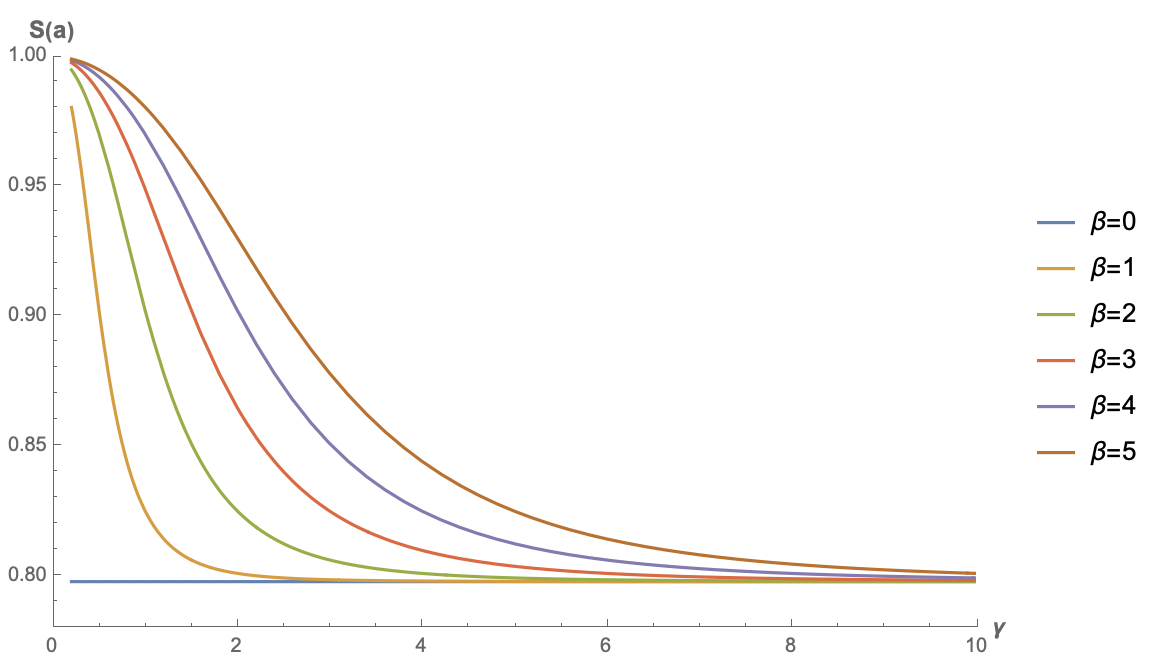

Now let's look at the simplest example: no $f$, or equivalently $f=\text{identical}$. This corresponds to the simplest type of Linear Attention. Similarly, using Mathematica for the calculation yields:

\begin{equation}S(\boldsymbol{a}) =\frac{\sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi }} \gamma e^{-\frac{\beta ^2}{2 \gamma ^2}}+\beta \text{erf}\left(\frac{\beta }{\sqrt{2} \gamma }\right)}{\sqrt{\beta ^2+\gamma ^2}}\end{equation}Below are function plots for different values of $\beta$:

Sparsity curve for simplistic linear attention

Note that here $S(\boldsymbol{a})$ is an even function with respect to $\beta$ (the reader might try to prove this), so the plot for $\beta < 0$ is the same as the plot for its opposite. Therefore, the figure only shows results for $\beta \geq 0$. As can be seen from the figure, the sparsity level of linear attention without any activation function cannot approach 0; instead, it has a high lower bound. This means that when the input sequence is long enough, this type of linear attention has no way to "focus attention" on key positions.

From "Exploration of Linear Attention: Must Attention Have a Softmax?" we know that the general form of linear attention is $a_j \propto g(\boldsymbol{q})\cdot h(\boldsymbol{k}_j)$, where $g, h$ are activation functions with non-negative ranges. Let $\tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}=g(\boldsymbol{q}), \tilde{\boldsymbol{k}}=h(\boldsymbol{k})$, then $a_j \propto \tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}^{\scriptscriptstyle\top}\tilde{\boldsymbol{k}}$. We can write:

\begin{equation}S(\boldsymbol{a}) = \frac{\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}\left[\tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}^{\scriptscriptstyle\top}\tilde{\boldsymbol{k}}\right]}{\sqrt{\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}\left[\tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}^{\scriptscriptstyle\top}\tilde{\boldsymbol{k}}\tilde{\boldsymbol{k}}^{\scriptscriptstyle\top}\tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}\right]}} = \frac{\tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}^{\scriptscriptstyle\top}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}\left[\tilde{\boldsymbol{k}}\right]}{\sqrt{\tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}^{\scriptscriptstyle\top}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}\left[\tilde{\boldsymbol{k}}\tilde{\boldsymbol{k}}^{\scriptscriptstyle\top}\right]\tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}}} = \frac{\tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}^{\scriptscriptstyle\top}\tilde{\boldsymbol{\mu}}}{\sqrt{\tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}^{\scriptscriptstyle\top}\left[\tilde{\boldsymbol{\mu}}\tilde{\boldsymbol{\mu}}^{\scriptscriptstyle\top} + \tilde{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}\right]\tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}}} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 + \frac{\tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}^{\scriptscriptstyle\top}\tilde{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}\tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}}{(\tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}^{\scriptscriptstyle\top}\tilde{\boldsymbol{\mu}})^2}}}\end{equation}This is a general result for non-negative linear attention without any approximations, where $\tilde{\boldsymbol{\mu}}, \tilde{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}$ are the mean vector and covariance matrix of the $\tilde{\boldsymbol{k}}$ sequence, respectively.

From this result, it is clear that non-negative linear attention can also be arbitrarily sparse (i.e., $S(\boldsymbol{a}) \to 0$). This only requires the mean to approach 0 or the covariance to approach $\infty$, meaning the signal-to-noise ratio of the $\tilde{\boldsymbol{k}}$ sequence should be as small as possible. However, the $\tilde{\boldsymbol{k}}$ sequence is a non-negative vector sequence. A non-negative sequence with a very small signal-to-noise ratio means that most elements in the sequence are similar. Thus, the information such a sequence can express is limited. It also implies that linear attention usually can only represent the importance of absolute positions (for example, a column in the Attention matrix being all 1s), rather than expressing the importance of relative positions well. This is essentially another manifestation of the low-rank bottleneck of linear attention.

To perceive the variation of $S(\boldsymbol{a})$ more vividly, let's assume a simplest case: each component of $\tilde{\boldsymbol{k}}$ is independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.). In this case, the mean vector simplifies to $\tilde{\mu}\boldsymbol{1}$ and the covariance matrix simplifies to $\tilde{\sigma}^2\boldsymbol{I}$. Then the formula for $S(\boldsymbol{a})$ further simplifies to:

\begin{equation}S(\boldsymbol{a}) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 + \left(\frac{\tilde{\sigma}}{\tilde{\mu}}\frac{\Vert\tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}\Vert_2}{\Vert\tilde{\boldsymbol{q}}\Vert_1}\right)^2}}\end{equation}This result is much more intuitive to observe. To make linear attention sparse, one direction is to increase $\frac{\tilde{\sigma}}{\tilde{\mu}}$, i.e., lower the signal-to-noise ratio of the $\tilde{\boldsymbol{k}}$ sequence. The other direction is to increase $\frac{\Vert\boldsymbol{q}\Vert_2}{\Vert\boldsymbol{q}\Vert_1}$. The maximum value of this factor is $\sqrt{d}$, where $d$ is the dimension of $\boldsymbol{q}$ and $\boldsymbol{k}$. Therefore, increasing it means increasing $d$. Increasing $d$ means raising the upper bound on the rank of the attention matrix. This aligns with the conclusion from the low-rank bottleneck perspective: only by increasing $d$ can the deficiencies of Linear Attention be fundamentally alleviated.

Notably, as analyzed in "Pathways to Transformer Upgrades: 5. Linear Attention as Infinite Dimensions," standard Attention can also be understood as a type of infinite-dimensional linear attention. This means that, theoretically, only by increasing $d$ to infinity can the gap between the two be completely bridged.

Finally, let's look at the linear RNN model series introduced in "Google's New Work Attempts to 'Resurrect' RNN: Can RNN Shine Again?" Their characteristic is an explicit recursion, which can be viewed as a simple Attention:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{a} = (a_1, a_2, \cdots, a_{n-1}, a_n) = (\lambda^{n-1}, \lambda^{n-2}, \cdots, \lambda, 1)\end{equation}where $\lambda \in (0, 1]$. We can calculate:

\begin{equation}S(\boldsymbol{a}) = \sqrt{\frac{1 - \lambda^n}{n(1-\lambda)}\frac{1+\lambda}{1+\lambda^n}} < \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\frac{1+\lambda}{(1-\lambda)(1+\lambda^n)}}\end{equation}When $\lambda < 1$, as long as $n \to \infty$, we always have $S(\boldsymbol{a}) \to 0$. Therefore, for linear RNN models with explicit decay, sparsity is not an issue. Its problem is that it can only express a fixed attention that decays as the relative distance increases, making it unable to adaptively focus on context that is sufficiently far away.

This article proposes the idea of examining the potential of different Attention mechanisms through the degree of sparsity of the Attention matrix. It concludes that quadratic Attention mechanisms have the potential to achieve arbitrarily sparse Attention matrices, while linear Attention is not easy to achieve such sparsity, or can only achieve absolute position-related sparsity. This may be one of the reasons why the capability of linear Attention is limited.