By 苏剑林 | April 20, 2020

Generative models have always been a theme of great interest to me, whether in the context of NLP or CV. In this article, we introduce a novel generative model from the paper "Batch norm with entropic regularization turns deterministic autoencoders into generative models," which the authors call EAE (Entropic AutoEncoder). What it aims to achieve is fundamentally consistent with Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), and the final results are also similar (slightly superior). Its novelty lies not so much in how well it generates, but in its unique and elegant line of thought. Furthermore, we will take this opportunity to learn a method for estimating statistics—the k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) method—which is a very useful non-parametric estimation technique.

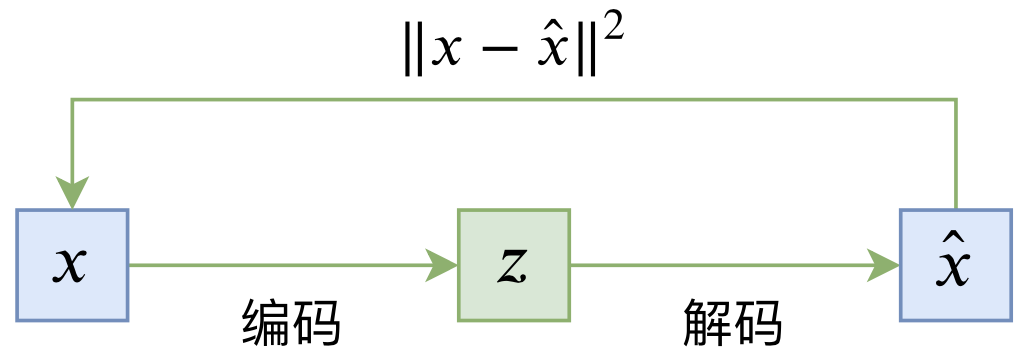

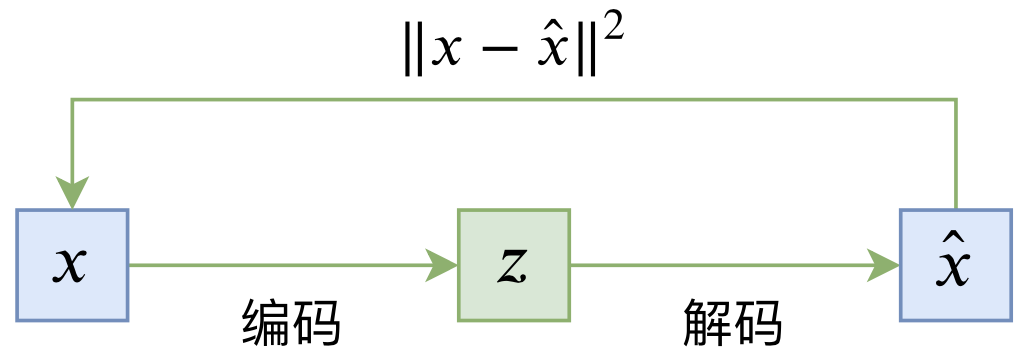

A standard autoencoder is a "coding-decoding" reconstruction process, as shown in the diagram below:

Its loss is generally given by:

\begin{equation}L_{AE} = \mathbb{E}_{x\sim \tilde{p}(x)}\left[\left\Vert x - \hat{x}\right\Vert^2\right] = \mathbb{E}_{x\sim \tilde{p}(x)}\left[\left\Vert x - D(E(x))\right\Vert^2\right]\end{equation}Once training is complete, we can naturally obtain the encoding $z=E(x)$ and the reconstructed image $\hat{x}=D(z)$ for any image $x$. When $x$ and $\hat{x}$ are sufficiently close, we can consider $z$ as an effective representation of $x$, as it contains sufficient information about $x$.

So, what is the situation for generative models? "Generation" refers to random generation, which means allowing us to construct an image at will. For the decoder $D(z)$ of an autoencoder, not every $z$ decoded will result in a meaningful image; therefore, a standard autoencoder cannot be regarded as a generative model. If we could know the distribution of $z=E(x)$ for all $x$ in advance, and if this distribution were easy to sample from, then we could achieve random sampling and generation.

Thus, the missing step from an autoencoder to a generative model is determining the distribution of the latent variable $z$, or more accurately, forcing the latent variable $z$ to follow a simple distribution that is easy to sample from, such as the standard normal distribution. VAEs achieve this by introducing a KL divergence term. How does EAE implement it?

As we know, the Principle of Maximum Entropy is a quite universal principle representing our most objective cognition of unknown events. One conclusion of the Maximum Entropy Principle is:

Among all distributions with a mean of 0 and a variance of 1, the standard normal distribution has the maximum entropy.

If readers are not yet familiar with Maximum Entropy, they can refer to the previous post "Can't Afford 'Entropy': From Entropy and Maximum Entropy Principle to Maximum Entropy Models (II)." The above conclusion tells us that if we have a means to ensure that the latent variable has a mean of 0 and a variance of 1, then we only need to simultaneously maximize the entropy of the latent variable to achieve the goal of having the "latent variable follow a standard normal distribution," i.e.,

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}&L_{EAE} = \mathbb{E}_{x\sim \tilde{p}(x)}\left[\left\Vert x - D(E(x))\right\Vert^2 \right] - \lambda H(Z)\\ &\text{s.t.}\,\,\text{avg}(E(x))=0,\,\text{std}(E(x))=1 \end{aligned}\end{equation}where $\lambda > 0$ is a hyperparameter, and

\begin{equation}H(Z)=\mathbb{E}_{z\sim p(z)}[-\log p(z)]\end{equation}is the entropy corresponding to the latent variable $z=E(x)$. Minimizing $-\lambda H(Z)$ means maximizing $\lambda H(Z)$, which is maximum entropy.

The questions are: how to guarantee these two constraints? And how to calculate the entropy of the latent variable?

Let's address the first question: how to achieve—or at least approximately achieve—the constraint that "the mean of the latent variable is 0 and the variance is 1"? Because only under the premise of satisfying this constraint is the maximum entropy distribution standard normal. The solution to this is the familiar Batch Normalization, or BN.

During the training phase of BN, we directly subtract the mean of each variable within the batch and divide by the standard deviation within the batch. This ensures that the mean of the variables in each training batch is indeed 0 and the variance is indeed 1. Then, it maintains a moving average of the mean and variance of each batch and caches them for prediction during the inference phase. In short, applying the BN layer to the latent variable allows it to (approximately) satisfy the corresponding mean and variance constraints. Note that the BN layer mentioned in this article does not include the two trainable parameters $\beta$ and $\gamma$. If using Keras, you should pass parameters scale=False, center=False when initializing the BN layer.

At this point, we obtain:

\begin{equation}L_{EAE} = \mathbb{E}_{x\sim \tilde{p}(x)}\left[\left\Vert x - D(\mathcal{N}(E(x)))\right\Vert^2\right] - \lambda H(Z)\label{eq:eae}\end{equation}Here, $\mathcal{N}(\cdot)$ represents the BN layer.

Now we come to the final and most hardcore part of the EAE model, which is how to estimate the entropy $H(Z)$. Theoretically, to calculate $H(Z)$, we need to know $p(z)$, but currently, we only have samples $z_1, z_2, \dots, z_n$ without knowing the expression for $p(z)$. Estimation of $H(Z)$ under such premises is called non-parametric estimation.

First, the conclusion:

Nearest Neighbor Estimation of Entropy: Let $z_1, z_2, \dots, z_n \in \mathbb{R}^d$ be $n$ samples drawn from $p(z)$, and let $\varepsilon(i)$ be the distance from $z_i$ to its nearest neighbor sample, i.e., $\varepsilon(i) = \min_{j\neq i} \Vert z_i - z_j \Vert$. If $B_d$ is the volume of the $d$-dimensional unit ball and $\gamma=0.5772\dots$ is the Euler-Mascheroni constant, then: \begin{equation}H(Z)\approx \frac{d}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \log \varepsilon(i) + \log B_d + \log (n - 1) + \gamma \label{eq:1nn}\end{equation}

Stripping away constants irrelevant to optimization, the above conclusion essentially says $H(Z) \sim \sum_{i=1}^n \log \varepsilon(i)$. This is the term we need to add to the loss.

How is this seemingly strange and difficult-to-understand result derived? In fact, it is a classic example of an important estimation method—the k-nearest neighbor method. Below is the derivation process, referenced from the paper "A non-parametric k-nearest neighbour entropy estimator."

Let's consider a specific sample $z_i$. Let $z_{i(k)}$ be its $k$-th nearest neighbor sample—that is, if we arrange all $z_j (j\neq i)$ in ascending order of $\Vert z_j - z_i\Vert$, the $k$-th one is $z_{i(k)}$. Denote $\varepsilon_k(i) = \Vert z_i - z_{i(k)}\Vert$. We now consider the probability distribution of $\varepsilon_k(i)$.

Suppose $\varepsilon \leq \varepsilon_k(i) \leq \varepsilon + d\varepsilon$. This means that among the remaining $n-1$ samples, $k-1$ samples fall inside the ball centered at $z_i$ with radius $\varepsilon$, and $n-k-1$ samples fall outside the ball centered at $z_i$ with radius $\varepsilon+d\varepsilon$, with one remaining sample caught between the two balls. It is not difficult to find that the probability of this occurring is: \begin{equation}\binom{n-1}{1}\binom{n-2}{k-1}P_i(\varepsilon)^{k-1}(1 - P_i(\varepsilon + d\varepsilon))^{n-k-1}(P_i(\varepsilon + d\varepsilon) - P_i(\varepsilon))\label{eq:dp-1}\end{equation} Where $\binom{n-1}{1}$ represents the number of combinations to choose 1 sample from $n-1$ to be between the two balls, and $\binom{n-2}{k-1}$ is the number of combinations to choose $k-1$ samples from the remaining $n-2$ to place inside the ball (the other $n-k-1$ automatically fall outside). $P_i(\varepsilon)$ is the probability that a single sample lies within the ball: \begin{equation}P_i(\varepsilon) = \int_{\Vert z - z_i\Vert \leq \varepsilon} p(z)dz\end{equation} Therefore, $P_i(\varepsilon)^{k-1}$ is the probability that the $k-1$ chosen samples are all in the ball, $(1 - P_i(\varepsilon + d\varepsilon))^{n-k-1}$ is the probability that $n-k-1$ samples are all outside, and $P_i(\varepsilon + d\varepsilon) - P_i(\varepsilon)$ is the probability of one sample being in the shell. Multiplying all terms gives expression \eqref{eq:dp-1}. Expanding and keeping only first-order terms yields the approximation: \begin{equation}\binom{n-1}{1}\binom{n-2}{k-1}P_i(\varepsilon)^{k-1}(1 - P_i(\varepsilon))^{n-k-1}dP_i(\varepsilon)\label{eq:dp-2}\end{equation} Note that the above expression describes a valid probability distribution, so its integral must be 1.

Now we can make an approximation assumption. It is worth noting that this is the only assumption in the entire derivation, and the reliability of the final result depends on how well this assumption holds: \begin{equation}p(z_i) \approx \frac{1}{B_d \varepsilon_k(i)^d}\int_{\Vert z - z_i\Vert \leq \varepsilon} p(z)dz = \frac{P_i(\varepsilon)}{B_d \varepsilon_k(i)^d}\end{equation} Where $B_d \varepsilon_k(i)^d$ is the volume of a ball with radius $\varepsilon_k(i)$. According to this approximation, we have $p(z_i) B_d \varepsilon_k(i)^d \approx P_i(\varepsilon)$. This might seem unreasonable because the left side is effectively a constant while the right side is a function of $\varepsilon$. How can they always remain approximately equal? In fact, when $n$ is large enough, the sampled points are sufficiently dense, so $\varepsilon$ will concentrate within a small range, and $\varepsilon_k(i)$ is a sampled value of $\varepsilon$. Thus, we can consider $\varepsilon$ to be concentrated near $\varepsilon_k(i)$. Although $P_i(\varepsilon)$ varies with respect to $\varepsilon$, we will later integrate over $\varepsilon$, so we only need a good approximation of $P_i(\varepsilon)$ near $\varepsilon_k(i)$; the approximation doesn't need to be good everywhere (i.e., when $\varepsilon \gg \varepsilon_k(i)$, \eqref{eq:dp-2} is nearly 0). Near $\varepsilon_k(i)$, we can assume the probability changes smoothly, so $p(z_i) B_d \varepsilon_k(i)^d \approx P_i(\varepsilon)$.

Now we can write: \begin{equation}\log p(z_i) \approx \log P_i(\varepsilon) - \log B_d - d \log \varepsilon_k(i) \end{equation} Multiply both sides by \eqref{eq:dp-2} and integrate over $\varepsilon$ (the integration interval is $[0, +\infty)$, or equivalently, integrate $P_i$ over $[0, 1]$). Except for $\log P_i(\varepsilon)$, the other terms are independent of $\varepsilon$, so they remain themselves after integration, while: \begin{equation}\begin{aligned}&\int_0^1 \binom{n-1}{1}\binom{n-2}{k-1}P_i(\varepsilon)^{k-1}(1 - P_i(\varepsilon))^{n-k-1} \log P_i(\varepsilon) d P_i(\varepsilon) \\ =&\psi(k)-\psi(n)\end{aligned}\end{equation} Where $\psi$ represents the digamma function. (Don't ask me how these integrals were calculated—I don't know, but I know they can be computed using Mathematica!)

Thus, we obtain the approximation: \begin{equation}\log p(z_i) \approx \psi(k)-\psi(n) - \log B_d - d \log \varepsilon_k(i) \end{equation} Therefore, the final approximation for entropy is: \begin{equation}\begin{aligned}H(Z)=&\,\mathbb{E}_{z\sim p(z)}[-\log p(z)]\\ \approx&\, -\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \log p(z_i)\\ \approx&\,\frac{d}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \log \varepsilon_k(i) + \log B_d + \psi(n)-\psi(k) \end{aligned}\label{eq:knn}\end{equation} This is a more general result than equation \eqref{eq:1nn}. In fact, \eqref{eq:1nn} is a special case of this formula with $k=1$, because $\psi(1)=-\gamma$ and $\psi(n)= \sum_{m=1}^{n-1}\frac{1}{m}-\gamma \approx \log(n-1)$; these conversion formulas can be found on Wikipedia.

As mentioned at the beginning, the k-nearest neighbor method is a very useful non-parametric estimation approach. It is also related to the IMLE model I introduced previously. However, I am not personally very familiar with k-NN methods and need to learn more. A found resource is "Lectures on the Nearest Neighbor Method." Additionally, regarding entropy estimation, one can refer to Stanford's material: "Theory and Practice of Differential Entropy Estimation."

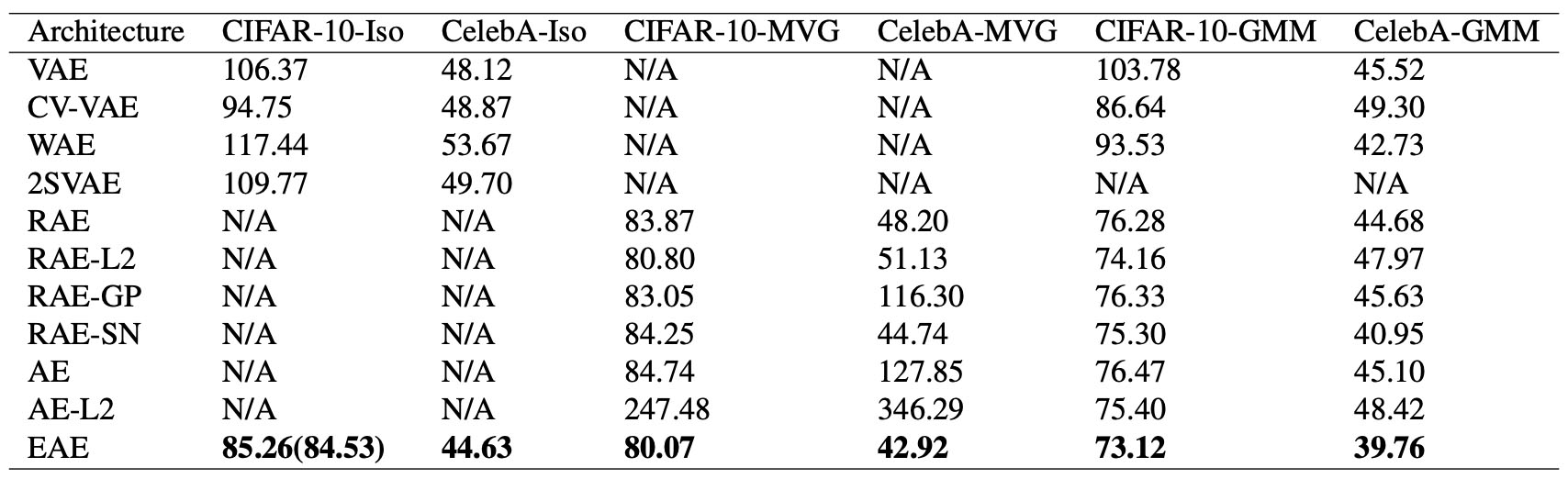

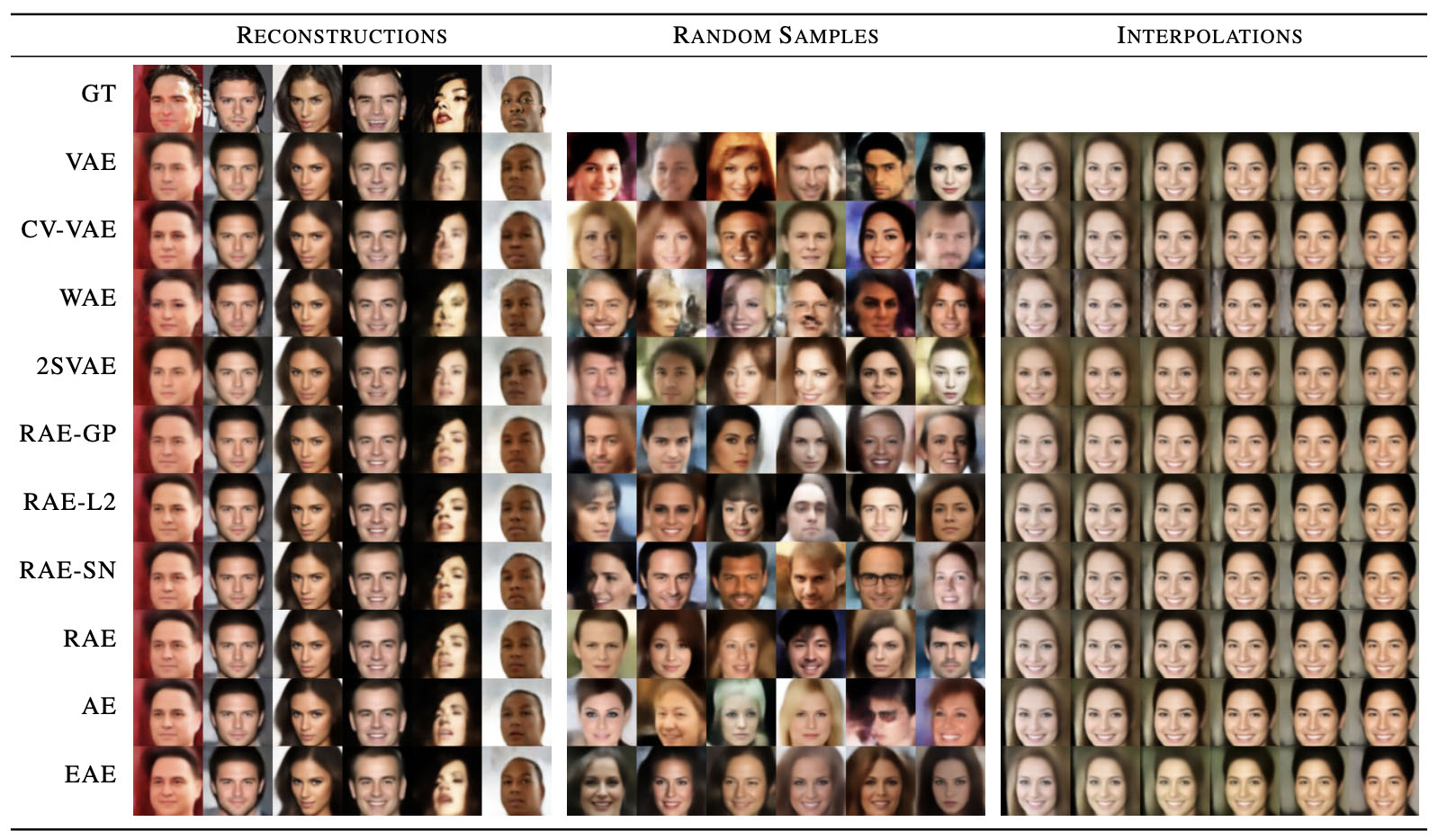

With \eqref{eq:1nn} or \eqref{eq:knn}, the Loss of EAE described in \eqref{eq:eae} is complete, so the EAE model introduction is finished. As for experimental results, I won't describe them in detail—suffice it to say that the generated images feel about the same as VAE, but the metrics are slightly better.

So, what is the advantage of EAE compared to VAE? In VAE, a key step is reparameterization (refer to my "Variational Autoencoder (I): So That's How It Works"). It is this step that reduces the training variance of the model (compared to REINFORCE, the variance is smaller, see "A Chat on Reparameterization: From Normal Distribution to Gumbel Softmax"), allowing VAEs to be trained effectively. However, although reparameterization reduces variance, the variance is actually still quite large. Simply put, the reparameterization step introduces significant noise (especially early in training), which may prevent the decoder from utilizing the encoder's information well. A classic example is the "KL vanishing" phenomenon when VAE is used in NLP.

EAE basically doesn't have this problem, because EAE is essentially a standard autoencoder. The addition of BN doesn't have much impact on autoencoding performance, and the added entropy regularization term, in principle, only increases the diversity of the latent variable without causing significant difficulty in the utilization or reconstruction of encoded information. I believe this is where EAE's advantage lies over VAE. Of course, I haven't done many experiments on EAE myself yet, so the above analysis is mostly a subjective inference; please distinguish it for yourself. If I have further experimental conclusions, I will share them with you on the blog.

This article introduced a model called EAE, which essentially stuffs a BN layer and maximum entropy into a standard autoencoder to give it generative model capabilities. Many experiments in the original paper show that EAE works better than VAE, so it should be a model worth studying and trying. Furthermore, the key part of EAE is estimating entropy through the k-nearest neighbor method, which is somewhat hardcore but actually very valuable and worth reading for readers interested in statistical estimation.