By 苏剑林 | June 13, 2022

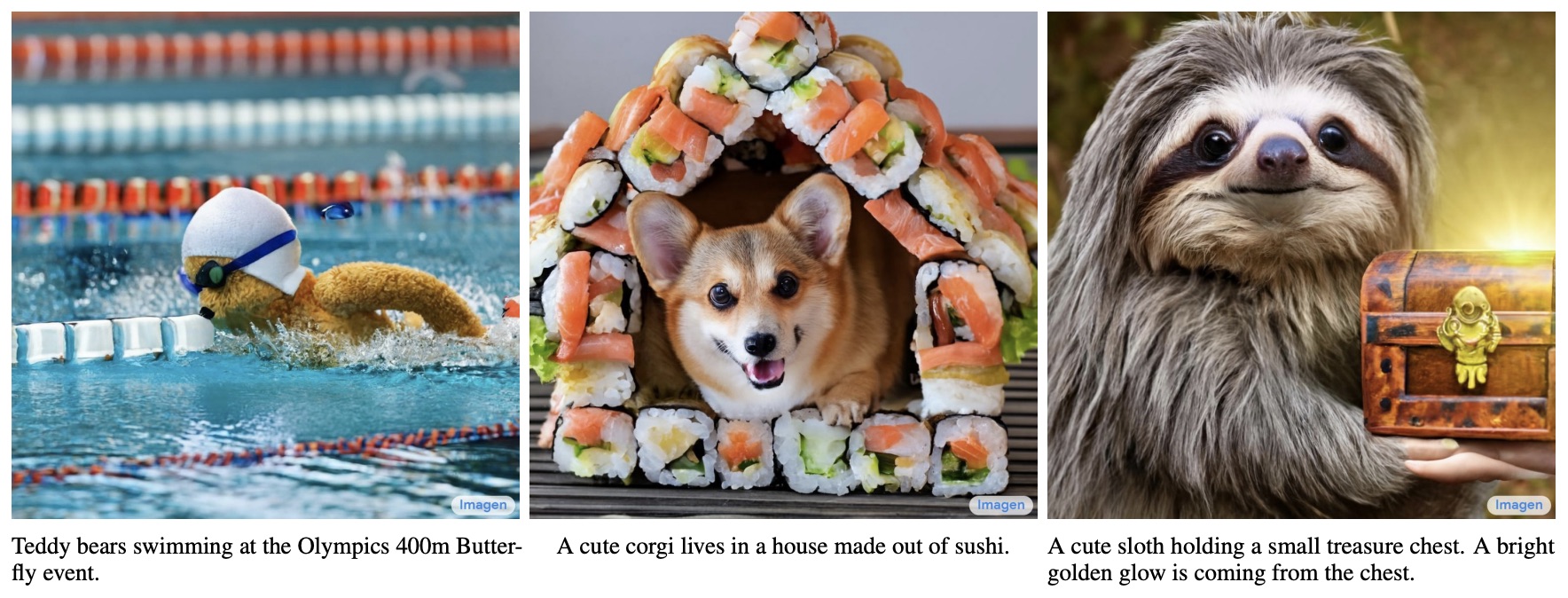

When it comes to generative models, VAE and GAN are certainly "household names," and this site has featured them many times. In addition, there are some niche choices such as flow models and VQ-VAE, which are also quite popular—especially VQ-VAE and its variant VQ-GAN, which have recently evolved into a "Tokenizer for images" used to directly invoke various NLP pre-training methods. Besides these, there is another choice that was originally even more niche—Diffusion Models—which is currently "rising sharply" in the field of generative models. The two most advanced text-to-image models at present—OpenAI's DALL·E 2 and Google's Imagen—are both completed based on diffusion models.

Some examples of "text-to-image" from Imagen

Starting from this article, we will open a new series to gradually introduce some progress in generative diffusion models over the past two years. Generating diffusion models are rumored to be famous for their mathematical complexity and seem much harder to understand than VAEs or GANs. Is this really the case? Can't diffusion models be understood in "plain language"? Let's wait and see.

A New Starting Point

Actually, in previous articles like "GAN Models from an Energy Perspective (3): Generative Model = Energy Model" and "From Denoising Autoencoders to Generative Models," we briefly introduced diffusion models. When talking about diffusion models, general articles mention Energy-based Models, Score Matching, the Langevin Equation, and so on. To put it simply, energy models are trained via score matching techniques, and then sampling from the energy model is executed via the Langevin equation.

Theoretically, this is a very mature scheme that, in principle, can achieve the generation and sampling of any continuous object (speech, images, etc.). But from a practical point of view, training an energy function is a difficult task, especially when the data dimensionality is large (such as high-resolution images), making it hard to train a complete energy function. On the other hand, sampling from energy models through the Langevin equation also has great uncertainty, often resulting in noisy sampling results. Therefore, for a long time, diffusion models following this traditional path were only experimented with on lower-resolution images.

The current popularity of generative diffusion models stems from DDPM (Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model) proposed in 2020. Although it uses the name "diffusion model," in fact, except for a certain similarity in the form of the sampling process, DDPM is essentially completely different from traditional diffusion models based on Langevin sampling. This is entirely a new starting point and a new chapter.

To be precise, it would be more accurate to call DDPM a "gradual change model." The name diffusion model is prone to causing misunderstanding; concepts like the energy model, score matching, and the Langevin equation from traditional diffusion models actually have nothing to do with DDPM and its subsequent variants. Interestingly, the mathematical framework of DDPM was actually completed in the ICML 2015 paper "Deep Unsupervised Learning using Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics," but DDPM was the first to successfully debug it for high-resolution image generation, leading to the subsequent hype. This shows that the birth and popularity of a model often require time and opportunity.

Demolition and Construction

Many articles, when introducing DDPM, start by introducing transition distributions followed by variational inference. A pile of mathematical notation scares off a group of people (of course, from this introduction, we can see again that DDPM is actually more like a VAE than a traditional diffusion model). Combined with people's inherent impression of traditional diffusion models, the illusion that "advanced mathematical knowledge is required" is formed. In fact, DDPM can also be understood in "plain language," and it is no harder than the popular analogy of "counterfeiting-identification" used for GANs.

First, if we want to make a generative model like GAN, it is essentially a process of transforming a random noise $\boldsymbol{z}$ into a data sample $\boldsymbol{x}$:

\begin{equation}\require{AMScd}\begin{CD}

\text{Random Noise } \boldsymbol{z} \quad @>\quad\text{Transform}\quad>> \quad\text{Sample Data } \boldsymbol{x}\\

@V \text{Analogy} VV @VV \text{Analogy} V\\

\text{Bricks and Cement} \quad @>\quad\text{Construct}\quad>> \quad\text{Skyscraper}\\

\end{CD}\end{equation}

Call me an engineer

We can imagine this process as "construction," where random noise $\boldsymbol{z}$ represents raw materials like bricks and cement, and sample data $\boldsymbol{x}$ represents a skyscraper. Thus, the generative model is a construction team that uses raw materials to build a skyscraper.

This process is certainly difficult, which is why there has been so much research into generative models. But as the saying goes, "destruction is easy, construction is hard." You might not know how to build a building, but you surely know how to tear one down, right? Let's consider the process of step-by-step tearing down a skyscraper into bricks and cement: let $\boldsymbol{x}_0$ be the finished skyscraper (data sample) and $\boldsymbol{x}_T$ be the demolished bricks and cement (random noise). Assuming "demolition" takes $T$ steps, the entire process can be represented as:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{x} = \boldsymbol{x}_0 \to \boldsymbol{x}_1 \to \boldsymbol{x}_2 \to \cdots \to \boldsymbol{x}_{T-1} \to \boldsymbol{x}_T = \boldsymbol{z}\end{equation}

The difficulty of building a skyscraper lies in the fact that the span from raw materials $\boldsymbol{x}_T$ to the final building $\boldsymbol{x}_0$ is too large. It is hard for ordinary people to understand how $\boldsymbol{x}_T$ suddenly becomes $\boldsymbol{x}_0$. However, once we have the intermediate steps of the "demolition" $\boldsymbol{x}_1, \boldsymbol{x}_2, \cdots, \boldsymbol{x}_T$, and we know that $\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} \to \boldsymbol{x}_t$ represents one step of demolition, then isn't $\boldsymbol{x}_t \to \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}$ conversely one step of construction? If we can learn the transformation relationship between the two, $\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} = \boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)$, then starting from $\boldsymbol{x}_T$ and repeatedly executing $\boldsymbol{x}_{T-1} = \boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_T), \boldsymbol{x}_{T-2} = \boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_{T-1}), \dots$, wouldn't we eventually be able to build the skyscraper $\boldsymbol{x}_0$?

How to Demolish

As the saying goes, "eat your meal one bite at a time," and a building must be built one step at a time. The process of DDPM as a generative model is completely consistent with the above "demolition-construction" analogy. It first builds a process that gradually changes from data samples to random noise and then considers its inverse transformation, completing data sample generation by repeatedly executing the inverse transformation. This is why it was said earlier that the DDPM approach should more accurately be called a "gradual change model" rather than a "diffusion model."

Specifically, DDPM models the "demolition" process as:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{x}_t = \alpha_t \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t, \quad \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t \sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})\label{eq:forward}\end{equation}

where $\alpha_t, \beta_t > 0$ and $\alpha_t^2 + \beta_t^2 = 1$. $\beta_t$ is usually very close to 0, representing the degree of damage to the original building in a single step of "demolition." The introduction of noise $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t$ represents a kind of damage to the original signal, which we can also understand as "raw materials"—that is, in each step of "demolition," we decompose $\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}$ into "building structure $\alpha_t \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}$ + raw material $\beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t$." (Note: The definitions of $\alpha_t, \beta_t$ in this article are different from the original paper.)

By repeatedly executing this demolition step, we can obtain:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}

\boldsymbol{x}_t =&\, \alpha_t \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t \\

=&\, \alpha_t \big(\alpha_{t-1} \boldsymbol{x}_{t-2} + \beta_{t-1} \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_{t-1}\big) + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t \\

=&\,\cdots\\

=&\,(\alpha_t\cdots\alpha_1) \boldsymbol{x}_0 + \underbrace{(\alpha_t\cdots\alpha_2)\beta_1 \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_1 + (alpha_t\cdots\alpha_3)\beta_2 \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_2 + \cdots + \alpha_t\beta_{t-1} \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_{t-1} + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t}_{\text{Sum of multiple independent normal noises}}

\end{aligned}\label{eq:expand}\end{equation}

The reader might have wondered why the superimposed coefficients must satisfy $\alpha_t^2 + \beta_t^2 = 1$. Now we can answer this question. First, the part pointed out by the curly braces is exactly the sum of multiple independent normal noises, with a mean of 0 and variances of $(\alpha_t\cdots\alpha_2)^2\beta_1^2, (\alpha_t\cdots\alpha_3)^2\beta_2^2, \cdots, \alpha_t^2\beta_{t-1}^2, \beta_t^2$, respectively. Then, using a piece of knowledge from probability theory—the additivity of normal distributions—it is known that the distribution of the sum of the above independent normal noises is actually a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance $(\alpha_t\cdots\alpha_2)^2\beta_1^2 + (\alpha_t\cdots\alpha_3)^2\beta_2^2 + \cdots + \alpha_t^2\beta_{t-1}^2 + \beta_t^2$. Finally, under the condition that $\alpha_t^2 + \beta_t^2 = 1$ always holds, we can find that the sum of the squares of the coefficients in Eq $\eqref{eq:expand}$ remains 1, i.e.,

\begin{equation}(\alpha_t\cdots\alpha_1)^2 + (\alpha_t\cdots\alpha_2)^2\beta_1^2 + (\alpha_t\cdots\alpha_3)^2\beta_2^2 + \cdots + \alpha_t^2\beta_{t-1}^2 + \beta_t^2 = 1\end{equation}

So it is actually equivalent to having:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{x}_t = \underbrace{(\alpha_t\cdots\alpha_1)}_{\text{denoted as } \bar{\alpha}_t} \boldsymbol{x}_0 + \underbrace{\sqrt{1 - (\alpha_t\cdots\alpha_1)^2}}_{\text{denoted as } \bar{\beta}_t} \bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_t, \quad \bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_t \sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})\label{eq:skip}\end{equation}

This provides great convenience for calculating $\boldsymbol{x}_t$. On the other hand, DDPM chooses an appropriate form for $\alpha_t$ such that $\bar{\alpha}_T \approx 0$, which means that after $T$ steps of demolition, the remaining building structure is almost negligible and has been entirely converted into raw material $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}$. (Note: The definition of $\bar{\alpha}_t$ in this article is different from the original paper.)

How to Build Again

"Demolition" is the process $\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} \to \boldsymbol{x}_t$. From this process, we obtain many data pairs $(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}, \boldsymbol{x}_t)$. Then "construction" naturally involves learning a model for $\boldsymbol{x}_t \to \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}$ from these data pairs. Let that model be $\boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)$. An easy learning scheme to think of is minimizing the Euclidean distance between the two:

\begin{equation}\left\Vert\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} - \boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)\right\Vert^2\label{eq:loss-0}\end{equation}

This is already very close to the final DDPM model. Next, let's make this process more refined. First, the "demolition" formula $\eqref{eq:forward}$ can be rewritten as $\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} = \frac{1}{\alpha_t}\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t - \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t\right)$. This inspires us that perhaps the "construction" model $\boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)$ can be designed in the form:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) = \frac{1}{\alpha_t}\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t - \beta_t \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)\right)\label{eq:sample}\end{equation}

where $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ are the training parameters. Substituting this into the loss function, we get:

\begin{equation}\left\Vert\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} - \boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)\right\Vert^2 = \frac{\beta_t^2}{\alpha_t^2}\left\Vert \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t - \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)\right\Vert^2\end{equation}

The leading factor $\frac{\beta_t^2}{\alpha_t^2}$ represents the weight of the loss, which we can temporarily ignore. Finally, substituting the expression for $\boldsymbol{x}_t$ given by combining Eq $\eqref{eq:skip}$ and $\eqref{eq:forward}$:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{x}_t = \alpha_t\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t = \alpha_t\left(\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}\boldsymbol{x}_0 + \bar{\beta}_{t-1}\bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1}\right) + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t = \bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0 + \alpha_t\bar{\beta}_{t-1}\bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1} + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t \end{equation}

The resulting form of the loss function is:

\begin{equation}\left\Vert \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t - \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0 + \alpha_t\bar{\beta}_{t-1}\bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1} + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t, t)\right\Vert^2\label{eq:loss-1}\end{equation}

The reader might ask: why go back one step to provide $\boldsymbol{x}_t$? Is it okay to provide $\boldsymbol{x}_t$ directly according to Eq $\eqref{eq:skip}$? The answer is no because we have already sampled $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t$ in advance, and $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t$ is not independent of $\bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_t$. Thus, given $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t$, we cannot sample $\bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_t$ completely independently.

Reducing Variance

In principle, the loss function $\eqref{eq:loss-1}$ could complete the training of DDPM, but in practice, it carries the risk of excessive variance, leading to problems like slow convergence. It isn't difficult to understand this; one just needs to observe that Eq $\eqref{eq:loss-1}$ actually contains 4 random variables that need to be sampled:

1. Sample $x_0$ from all training samples;

2. Sample $\bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1}$ and $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t$ from the normal distribution $\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})$ (two different sampling results);

3. Sample a $t$ from $1 \sim T$.

The more random variables that need to be sampled, the harder it is to accurately estimate the loss function. Conversely, the fluctuation (variance) of each estimate of the loss function is too large. Fortunately, we can use an integration trick to merge $\bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1}$ and $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t$ into a single normal random variable, thereby alleviating the problem of high variance.

This integration indeed requires some trickery, but it is not overly complex. Due to the additivity of normal distributions, we know that $\alpha_t\bar{\beta}_{t-1}\bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1} + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t$ is actually equivalent to a single random variable $\bar{\beta}_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}$ where $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon} \sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})$. Similarly, $\beta_t \bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1} - \alpha_t\bar{\beta}_{t-1} \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t$ is equivalent to a single random variable $\bar{\beta}_t \boldsymbol{\omega}$ where $\boldsymbol{\omega} \sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})$. It can be verified that $\mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}\boldsymbol{\omega}^{\top}] = \boldsymbol{0}$, so these are two independent normal random variables.

Next, we represent $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t$ back in terms of $\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}$ and $\boldsymbol{\omega}$:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t = \frac{(\beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon} - \alpha_t\bar{\beta}_{t-1} \boldsymbol{\omega})\bar{\beta}_t}{\beta_t^2 + \alpha_t^2\bar{\beta}_{t-1}^2} = \frac{\beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon} - \alpha_t\bar{\beta}_{t-1} \boldsymbol{\omega}}{\bar{\beta}_t}\end{equation}

Substituting this into Eq $\eqref{eq:loss-1}$ gives:

\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}

&\,\mathbb{E}_{\bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1}, \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t\sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})}\left[\left\Vert \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t - \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0 + \alpha_t\bar{\beta}_{t-1}\bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1} + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t, t)\right\Vert^2\right] \\

=&\,\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{\omega}, \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}\sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})}\left[\left\Vert \frac{\beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon} - \alpha_t\bar{\beta}_{t-1} \boldsymbol{\omega}}{\bar{\beta}_t} - \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0 + \bar{\beta}_t\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}, t)\right\Vert^2\right]

\end{aligned}\end{equation}

Notice that now the loss function is only quadratic with respect to $\boldsymbol{\omega}$. We can expand it and directly calculate its expectation. The result is:

\begin{equation}\frac{\beta_t^2}{\bar{\beta}_t^2}\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}\sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})}\left[\left\Vert\boldsymbol{\varepsilon} - \frac{\bar{\beta}_t}{\beta_t}\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0 + \bar{\beta}_t\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}, t)\right\Vert^2\right]+\text{constant}\end{equation}

By again discarding the constant and the loss function weights, we obtain the final loss function used by DDPM:

\begin{equation}\left\Vert\boldsymbol{\varepsilon} - \frac{\bar{\beta}_t}{\beta_t}\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0 + \bar{\beta}_t\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}, t)\right\Vert^2\end{equation}

(Note: The $\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}$ in the original paper is actually $\frac{\bar{\beta}_t}{\beta_t}\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}$ in this article, so everyone's results are perfectly identical.)

Recursive Generation

So far, we have cleared up the entire training process of DDPM. Quite a bit has been written. You couldn't say it's easy, but there are almost no truly difficult parts—it doesn't use tools like traditional energy functions or score matching, or even knowledge of variational inference. It merely relies on the "demolition-construction" analogy and some basic probability theory to arrive at the exact same results as the original paper. In general, this shows that the newly emerging generative diffusion models represented by DDPM can actually find an image analogy like GANs. It can be seen as an intuitive modeling of how we learn new knowledge from the process of "dismantling and reassembling."

After training, we can start from a random noise $\boldsymbol{x}_T \sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})$ and execute $T$ steps of Eq $\eqref{eq:sample}$ for generation:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} = \frac{1}{\alpha_t}\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t - \beta_t \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)\right)\end{equation}

This corresponds to Greedy Search in autoregressive decoding. If you want to perform Random Sampling, then you need to add back the noise term:

\begin{equation}\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} = \frac{1}{\alpha_t}\left(\boldsymbol{x}_t - \beta_t \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)\right) + \sigma_t \boldsymbol{z}, \quad \boldsymbol{z} \sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})\end{equation}

Generally, we can let $\sigma_t = \beta_t$, keeping the forward and backward variances synchronized. The difference between this sampling process and the Langevin sampling of traditional diffusion models is: each DDPM sampling starts from a random noise and requires $T$ iterative steps to get a single sample output; Langevin sampling starts from any point and iterates infinitely many steps. Theoretically, in this process of infinite iterations, all data samples will have been generated. So, besides the similarity in form, the two are essentially different models.

From this production process, we can also feel that it is actually the same as the decoding process in Seq2Seq; both are series-style autoregressive generation. Therefore, generation speed is a bottleneck. DDPM sets $T=1000$, which means that to generate one image, $\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t)$ must be executed 1000 times. Thus, a major drawback of DDPM is its slow sampling speed, and much subsequent work has focused on improving DDPM's sampling speed. Speaking of "image generation + autoregressive model + very slow," some readers might think of early models like PixelRNN and PixelCNN. They convert image generation into a language modeling task, so they also perform recursive sampling and are equally slow. What is the substantive difference then between the autoregressive generation of DDPM and that of PixelRNN/PixelCNN? Why didn't PixelRNN/PixelCNN take off, whereas DDPM did?

Readers familiar with PixelRNN/PixelCNN know that these generative models generate images pixel by pixel. Since autoregressive generation is ordered, we have to arrange the order of every pixel in the image in advance, and the final generation effect is closely related to this order. However, currently, this order can only be manually designed based on experience (these empirical designs are collectively referred to as "Inductive Bias"), and an optimal theoretical solution cannot be found. In other words, the generation effect of PixelRNN/PixelCNN is heavily influenced by Inductive Bias. But DDPM is different; it redefines an autoregressive direction through the "demolition" method. For all pixels, they are equal and unbiased, thus reducing the impact of Inductive Bias and improving the results. Furthermore, the number of iterative steps in DDPM generation is fixed at $T$, whereas in PixelRNN/PixelCNN, it equals the image resolution ($\text{width} \times \text{height} \times \text{channels}$). Therefore, DDPM's speed in generating high-resolution images is much faster than that of PixelRNN/PixelCNN.

Hyperparameter Settings

In this section, we discuss the setting of hyperparameters.

In DDPM, $T=1000$, which might be larger than many readers imagine. Why set $T$ to be so large? On the other hand, regarding the choice of $\alpha_t$, translating the original paper's settings into the notation of this blog is roughly:

\begin{equation}\alpha_t = \sqrt{1 - \frac{0.02t}{T}}\end{equation}

This is a monotonically decreasing function. Why choose a monotonically decreasing $\alpha_t$?

Actually, these two questions have similar answers related to the specific context of the data. For simplicity, we used Euclidean distance $\eqref{eq:loss-0}$ as the loss function during reconstruction. As readers who have done image generation before know, Euclidean distance is not a good metric for the realism of an image. When VAE uses Euclidean distance for reconstruction, it often yields blurry results unless the input and output images are very close, in which case Euclidean distance can produce clearer results. Therefore, choosing a $T$ as large as possible is precisely to make the input and output as similar as possible, reducing the blurring problem caused by Euclidean distance.

Choosing a monotonically decreasing $\alpha_t$ is based on similar considerations. When $t$ is small, $\boldsymbol{x}_t$ is still close to the real image, so we want to reduce the difference between $\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}$ and $\boldsymbol{x}_t$ to make Euclidean distance $\eqref{eq:loss-0}$ more applicable; hence, a larger $\alpha_t$ is used. When $t$ is large, $\boldsymbol{x}_t$ is already close to pure noise. Noise is fine with Euclidean distance, so the difference between $\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}$ and $\boldsymbol{x}_t$ can be slightly increased, meaning a smaller $\alpha_t$ can be used. So, can one use a large $\alpha_t$ all the way through? Yes, you can, but then $T$ must be increased. Note that when deriving $\eqref{eq:skip}$, we said that we should have $\bar{\alpha}_T \approx 0$, and we can directly estimate:

\begin{equation}\log \bar{\alpha}_T = \sum_{t=1}^T \log\alpha_t = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{t=1}^T \log\left(1 - \frac{0.02t}{T}\right) < \frac{1}{2} \sum_{t=1}^T \left(- \frac{0.02t}{T}\right) = -0.005(T+1)\end{equation}

Plugging in $T=1000$ yields roughly $\bar{\alpha}_T \approx e^{-5}$, which just reaches the standard of $\approx 0$. Therefore, if a large $\alpha_t$ is used from beginning to end, then a larger $T$ is inevitably required to make $\bar{\alpha}_T \approx 0$.

Finally, we notice that in the "construction" model $\boldsymbol{\epsilon}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\bar{\alpha}_t\boldsymbol{x}_0 + \bar{\beta}_t\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}, t)$, we explicitly write $t$ in the input. This is because, in principle, different $t$ values process objects at different levels, so different reconstruction models should be used. This implies there should be $T$ different reconstruction models. Thus, we share the parameters of all reconstruction models and pass $t$ as a condition. According to the paper's appendix, $t$ is converted into the sinusoidal position encoding introduced in "Transformer Upgrade Road: 1. Tracing the Source of Sinusoidal Position Encoding" and then added directly to the residual blocks.

Summary

This article introduced the latest generative diffusion model, DDPM, from the popular analogy of "demolition-construction." From this perspective, we can obtain the exact same results as the original paper through "plain language" descriptions and relatively little mathematical derivation. Overall, this article shows that DDPM can also find a visual analogy like GANs. It doesn't need to use the "variation" from VAE, nor does it need to use "probability divergence" or "optimal transport" from GANs. In this sense, DDPM can even be considered simpler than VAE and GAN.